© 1935, Fox Film Corp

Like most Westerners of my generation the author came to know China and especially the Chinese from Western actors playing Asians in “yellowface” in The Good Earth and Charlie Chanfilms. The Chinese on film have come a long way since then, including one film that inspired the author to write his first novel. But I must hasten to clarify that my “take” on Chinese in film is not as a student of Chinese film, which is a substantial subject in its own right; nor is it derived from movies that were made by Chinese directors that have been produced by Chinese in Mandarin and Cantonese, which are discussed by much more knowledgably by others.* It is an American “take” primarily on the perspective of China and the Chinese through American produced motion pictures.

Any choice of films from the thousands of candidates is necessarily selective and subjective, which is why discussion of kung fu and the genre of flying daggers and green screen acrobatics are also absent below; my preference is for films with narrative, credible characters and “location,” not two cliché John Woo guys with guns at each others’ heads. Those that I have selected are a few from a larger number that I have seen (some multiple times), and the “take” on them, as cinema and as what they say to me about China and, particularly, Hollywood’s perspective on the Chinese, is also very much my own “take.” The reader therefore rightly might well ask why I did not include this or that movie. I might never have got around to seeing it.**

Scenes from a Movie

The woman was from that Ohio group that had been in lockstep with my group all through the Forbidden City. Everybody else in both groups had gone on to the next pavilion, leaving the two of us, temporarily alone. We stood silently few feet apart along the barrier that separates tourists from the gilded Emperor’s throne, perhaps ten meters up some broad stairs. Lost in our own thoughts we were both staring at the throne; but even before a word was uttered it seems we two strangers must shared the same thoughts, their connection mediated by that throne, and by a movie.

We looked at one another as if on cue; she spoke first, but it was almost unnecessary: “I wonder if it is still there?” she said, wistfully. I knew what she meant, as she must have assumed I would, the “it” being unreferenced. I even understood, shared, her sentimentality.

“The cricket cage,” I replied.

“Yes,” she answered, and pausing, “and maybe the cricket, too.” We turned in unison to look back up at the throne.

“Why not,” I said. I knew that we had both willingly suspended our disbelief to accept the narrative of The Last Emperor, Bertolucci’s magnificent epic of the last Manchu Emperor of China. Standing before that throne we were both returned to the two scenes in the movie, one in which the boy Emperor, Pu Yi, secrets his cricket cage, with its cricket in the cushion of that throne, and later in the movie when the now elderly Henry Pu Yi, a simple gardener in some hutong, perhaps not too far in distance, but ages away in time and circumstance, returns to the same place were we are standing, and sneaks up to what was once his throne. There, as only the movies can do with time, he rediscovers his cricket cage, and the living cricket therein.

It is a magnificent expression of cinema’s imaginative capacities, the ability to create an indelible moment that maybe only part truth, maybe not true that all, yet expresses the universal truth of its own—that something that is not or was not, ought to have been. And, that lady whose name I never learned and who I never saw again, had a connection in that truth, one that we had brought with us to the forbidden city that day, perhaps both being subtly, but inexorably, drawn to the scene of that scene, the silent, inactive, throne room on that sweltering summer day, shared by us both as cinema time travelers, willing suspenders of disbelief, and willing believers in the magic of cinema.

The Hollywood Lens

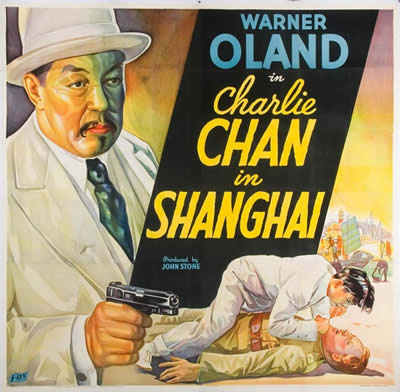

The Charlie Chan series of over forty films from 1921 to 1949 never had an Asian actor in the role. Warner Oland played the lead until his death and was replaced by Sidney Toler, followed by Roland Winters after Toler’s death (only Chan sons, Number One Son, Keye Luke, and “Number Two Son,” Sen Yung, were Asians). Charlie was always brilliant, solving mysteries with a combination of deduction and Chinese aphorisms like “Sometimes insignificant molehill more important than conspicuous mountain,” which he delivered with the missing articles and simple tenses of Chinese fractured English.*** Charlie Chan’s was most recent resurrection was inCharlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen (1981), with Chan played by British actor, Peter Ustinov.

Even when American producers got around to hiring Asian actors, they seemed to regard them as culturally interchangeable. In the Oscar and Hammerstein musical, Flower Drum Song (1961) about a Chinese girl who smuggles herself into San Francisco, the cast includes Nancy Kwan (Chinese-English), James Shigeta and Myoshi Umecki (Japanese), Jack Soo (Chinese), and Juanita Hall (African-American), all playing Chinese roles. Then, of course there was the ultimate absurdity of John Wayne squinting his way through The Conqueror (1956) failing to convince anyone that he was a credible Ghengis Khan while striding around Mongolia (actually Utah) in his unmistakable gait as though he were on his way to a cattle round-up in a John Ford classic. Asian parts seem to have been cast as though the Asian personality was regarded as so stereotypically “inscrutable” that Western audiences would be unable to apprehend the subtleties of a performance by a real Chinese in the role of a Chinese.

Even when Hollywood had its own “home grown” Chinese actress it seemed unable to get over this problem. Before she died of a heart attack in 1961 Anna May Wong had “died a thousand deaths” on screen.**** As America’s first Asian lady of the movies, Wong was typecast as the “dragon lady,” the femme fatale of the East and other racist stereotypes of Asians who, for decades, were relegated to minor roles and “atmosphere” from the days of silent movies. Prevented from leading roles by de facto racist attitudes, and from even kissing a Caucasian on screen by “de jure” equivalents, she persisted against conditions that might have sent a lesser person back to being a delivery girl for her father’s Chinese laundry in Los Angeles. But Anna May dutifully let herself be dispatched, or committed suicide, so that something could be done with the Asian “alien” character that American movie audiences couldn’t quite fit into the picture.

Born right in Los Angeles, Anna May started out in silent films—with a role in Toll of the Sea(1922) when she was just seventeen—and made the transition to sound pictures with apparent ease, probably because she had such small speaking parts, but also because she had a softy, sultry voice when called upon. Although she was under contract to Paramount the studio exploited her, paying her much less than they paid Caucasian actors for equivalent work. She supplemented with modeling work thanks to her exotic beauty and slim, shapely figure, from which she contributed to the educations of her several brothers and sister (including one son from her father’s Chinese wife who still lived back in Taishan in southern China). Anna May was the only one not to earn a university degree. Not that Anna May was without intellectual interests ort abilities. She read widely, counted artists, writers among her lifelong friends and acquaintances, and, when she boldly took herself to Europe in search of better roles, and acquired fluency in German and French. She became a bigger star there than in her home country.

Ironically, Anna May never seemed to be able to gain acceptance in China where roles she had played as servants or dragon ladies were regarded as an insult to the Chinese culture. In part, the homeland Chinese disaffection for her work also owes something to the general low regard the Chinese have for “overseas” Chinese. Amazingly, Anna May was able to fashion a film career between the Scylla of Western discrimination, and Charybdis of Eastern opprobrium without going under. What may have sustained her was the respect and friendship she received from fellow actors, like Paul Robson, and cinematographer-director, James Wong Howe. She also formed friendships among intellectuals in America and Europe.

But the insults of negative stereotyping continued to haunt her films. In Shanghai Express(1932) Marlene Dietrich plays a call girl, but Wong (Hui Fei, the last name meaning a prostitute or concubine in Chinese) is cast more darkly, as a sullen and sultry “dragon lady” who is raped by a warlord. But eventually she turns out to be the heroine of the film, stabbing the warlord, Chang (played by non-Asian Warner Oland) and allowing all to escape his clutches. But the story quickly reverts to the love relationship between Dietrich and her male co-star. Wong actually did get a lead role in Bombs Over Burma (1943), a role that required she make love to a Japanese officer (Wong hated the Japanese and what they were doing to China) to save the people of her village. She kills the officer, but is herself executed.

Given a chance to give some non-stereotypical shape to a role Wong proved to be a facile and naturalistic actress. She was graceful in her movements and gestures, had a velvety voice, and could be expressive well beyond the impassive inscrutability required of most of the characters she played. Still, most people don’t remember her, or know of her as Hollywood’s first Asian actress who blazed a trail through prejudice, discrimination and stereotype for later Asian actresses Nancy Kwan, Joan Chen, France Nuyen, and Lucy Liu, and Vivian Wu.

Wong never married. She had several lovers, all of them Caucasian, at least one for whom she was “the other woman,” relationships that never seemed to lead toward marriage or evolved into friendships. In that sense she seems well within the “tradition” of film and literature’s failed love affairs between Asians and westerners. However, she kept many friends, of different races and nationalities, for life. How much of that owes to her personality, or the fact that she was so unique and rare in her profession. What is clear is that at the personal level there was far more depth and dimension to her than was ever allowed to be expressed in her film roles. Her place in film history is a bit like many of the roles she played; she was the inscrutable Asian, often in the shadowland between East and West.

[To be continued]

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.3.2014)