© 2012, UrbisMedia

Polls have shown that America, perhaps the most metaphysically credulous country in the world, would more likely be willing to elect a Muslim or a Mormon as their president than they would an atheist. That’s right, they would be more comfortable with the president who claims he has a personal relationship with Jesus, or concludes every other sentence with “inshallah,” or wears magic underwear, than someone who has the critical faculty of an open mind to see all of that stuff as bullshit that not only is irrelevant to democratic governance, but is far more likely to impede it.

That’s right, an atheist might actually make a better president then a believer of any denominational stripe. But we all know that the very word atheist scares the metaphysical poop out of most Americans. Regrettably, what does not seem to frighten Americans are candidates for the presidency like Rick Santorum, who sounds more like he’s running for Pope, or like Mitt Romney, who will turn himself into a rhetorical pretzel trying to avoid talking about his cult-like religion that call themselves “saints,” and whose scripture regards black people as “cursed.” Their previous “God chosen” president from Texas has presumably already received absolution for his preemptive wars and destructive economic policies. Sometimes it is just damn hard to believe this is the 21st century; too many people just believe that one is not worthy of public office if they do not believe in fairytales.

Believers and Atheists

Because belief injects faith into history––since belief is a narrative––it is concerned with those whose behaviors that might interfere with what is prophesied by that narrative. If one believe that there is a certain outcome, an Armageddon or an End Times or some other historicaldenouement, as well as the prophesied events that are to lead up to it, then any interference with that is heretical. Hence, infidels are not to be tolerated and, if they are not converted, then they must be exterminated, but they cannot be simply ignored. Belief does not tolerate atheism, which in the least represents a failure of belief systems, and at the worst challenges them. Nonbelief therefore generates evangelism. Is it any wonder then that version or extermination has been such a prominent causus belli and jus ad bellum throughout history and to the present day? Belief cannot tolerate unbelief because the rejection of what is believed is tantamount to threat; that must be converted, or expunged

.

Atheism is however not the contraposition, but the negation, of the effects of belief. That is, atheism is not bent on enforcing its own version of the end of history, some soteriological and eschatological dénouement to life on earth; but atheism posits a nihilistic response those positions.*

Ask an atheist: what is heaven like? What heaven? Whether Jesus is the son of God? What God? How to achieve salvation? Salvation from what?

There are no relevant answers to irrelevant questions. Thus atheism has no interest in your not believing, not in the way that belief seeks credit, or merit for converting the atheist. Atheism has little concern for your joining its non-theistic position other than it might make for one less annoying evangelist or dangerous zealot. An atheist might be interested in a good mixed–intellectual–arts scuffle, but is not likely to be interested and converting you (other than to rejecting the notion that atheists are agents of the Devil).

The atheist is far less, if at all, interested in testifying, in professing his (non)faith, of asserting his (non)metaphysical beliefs, to impress others, or to impress a God. Atheism is not another, alternative, faith, but the negation of faith.

And the strife, wars, persecutions, pogroms and other mayhem visited on the planet by believers might be avoided or diminished if there were more agnostics and atheists (fortunately slowly, but inexorably, growing in number) in charge of public affairs.

But atheists do not live in an atmosphere of total disbelief. There are many things for which we do not have certainty and many for which information is only partial. I can believe that OJ murdered his wife and her boyfriend. It has to be “believed” because I cannot know it with certainty although my belief may (should) be based on something, some evidence, logic, information, and not that I don’t happen to like African American running backs or some other arbitrary aspect of prejudice.

But I could also believe that the Devil exists without the faintest evidence to support it. I could believe that the Devil made OJ killed his wife, and I could also believe in a place called Hell, and OJ will (believing in a form of eternity as well), end up in Hell forever. But I don’t believe in any of that.

I can believe in myself, that is having the self-confidence to do, or, wish, something. I could believe in my talents or abilities and I can also believe and their limitations. I can believe in principles, such as equality, freedom, tolerance, that these are good and proper pursuits for the good society. I can buttress this belief with historical examples and statistical evidence.

The important distinction here is that, while rationalists can also have beliefs, they are conditional. We hold them until more evidence comes along, better information, empirical proofs, and such move us to revise those beliefs, moving them closer to what we consider “knowledge.” This is where we differ from the true believer who it is willing, if not eager, to believe in the case of the existence of God, heaven, Hell, and the rest of it, completely without the slightest evidence; but is unwilling to give any consideration to the proposition that they might not exist at all.

But given the heavy epistemological requirements for true knowledge there is a lot of believing we have to do to make decisions in life. I just don’t believe that if I pray for guidance that is the best way to make my decisions, I don’t believe that my guardian angel will keep me from getting hit by a bus, I don’t believe that St. Anthony help me find my car keys. I don’t believe in living in religious induced fear of an imaginary fate that hovers between my profession of faith and eternal damnation. If other people want to live their life in a willing suspension of rationality then so be it. But it has proven to be a hell of a way around the world.

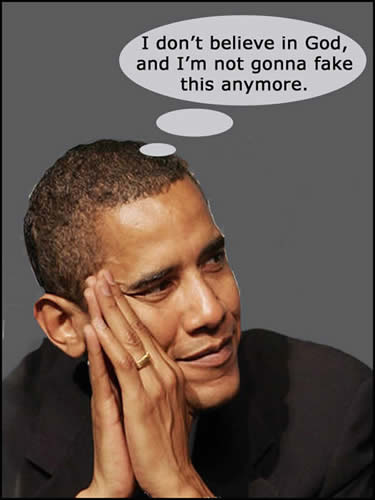

So maybe it’s time for an atheist to step up and run for the presidency, or even some politician who has felt obliged to professes his religious faith to admit that his belief has been more a matter of convenience than conviction, that his attendance at those “prayer breakfasts” has been more faking it than fidelity. Wouldn’t it be more credible if he stood up and said “I don’t believe in God, and I’m not going to fake it anymore.” What have you got to lose? Maybe it’s time to stop worrying about the fate of your imaginary “immortal soul” and get real about your corporeal here and now.

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.5.2012)

*I will concede that some putatively atheistic philosophies, such as communism, perceive some sort of “final stage” or sort of a static end state in the historical processes that bring them into being; but we all know that process is process, we all know as Heraclitus has taught us so well that everything changes nothing remains the same.