What I learned over thirty years as “Dr. Fate” from my students’ adventures in “lifeboats”

It is now a century since that fateful night in August 1912 when the reputedly unsinkable ocean linerTitanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic. By now, thanks to a spate of movies recounting the story, the discovery of the wreck of the ship in 1985, numerous documentaries, the recovery and auction of artifacts, and dozens of books, several of which I’ve read, just about everybody knows something about most famous non-military sea disaster in maritime history.

It is now a century since that fateful night in August 1912 when the reputedly unsinkable ocean linerTitanic collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic. By now, thanks to a spate of movies recounting the story, the discovery of the wreck of the ship in 1985, numerous documentaries, the recovery and auction of artifacts, and dozens of books, several of which I’ve read, just about everybody knows something about most famous non-military sea disaster in maritime history.

The Titanic story continues to captivate us. It has all the dramatic elements one could ask for: technology versus nature, the sociology of rich and poor, and courage and cowardice rolled into the events of a few hours in the icy calm seas and one night. There is more than enough in it that there was hardly a need to add the fictional love story brought to it in James Cameron’s immensely successful Titanic in 1997. But that was a way, I suppose, in which we all, or at least those of us who were blessed with the gene for willing suspension of disbelief, are able to imagine ourselves in this drama.

I can’t recall when I fist saw Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944), or whether it was before or after I first saw A Night To Remember (1958), the second movie to deal with the Titanic disaster. Lifeboat was not about the Titanic, but about survivors from a passenger liner torpedoed by a German U-boat in the North Atlantic in World War II. Directed by Alfred HJitchcock, it had a wonderful cast and a plot twist that the lifeboat survivors happen to rescue the captain of the U-boat that sank them.

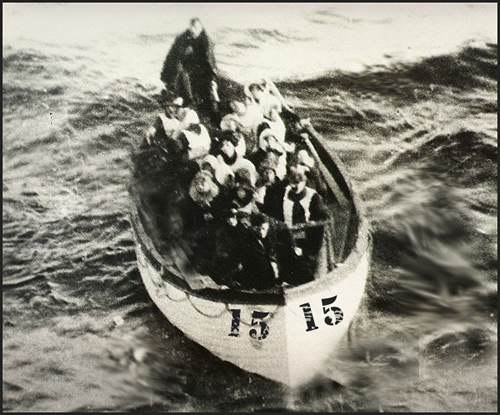

I saw Lifeboat again sometime in the late 1970s. This was a time when games and simulations were coming into popularity in pedagogy at all levels and I was wondering what kind of simulation might be appropriate for my graduate course in Planning Theory. And so over a period of several days I sketched out a scenario and a simulation that involved placing fifteen students in a “lifeboat” formed by fifteen chairs tightly arranged in an elliptical boat form in the middle of a classroom floor that would represent the stormy seas of the North Atlantic. In that original version I described the features of the simulation that proved to hold up over the next three decades of applying it in my own classrooms, the classrooms of other professors and disciplines, and with students from Asia. I wrote:

Lifeboat 15 is a simulation designed to for a variety of instructional purposes. The elements of the simulation have been fashioned to mirror aspects of modern urban society, including such general features as decision-making under crisis conditions, cooperation and competition, risk-taking, the ethical dimensions of decision-making, and considerations in the “rational” distribution of finite resources.

The simulation employs “roles” that attempt to create a social cross-section of society, although it is not a role-playing simulation per se. Rather, the roles place participants in a social context, in some cases providing for greater power or influence over decisions, in other cases placing constraints and limitations, in ways that are roughly analogous to privileged, underprivileged and disadvantaged segments of society.

The players of the simulation, while they were assigned specific “roles,” were instructed to infuse those roles with their own values, mores, and even personalities. They were to be, in a sense, “method actors” in a drama that they themselves would be scripting.

My intent was to “provoke,” in two and one-half to three hour simulation in which the students were crammed together in a “lifeboat,” a social crisis that would bring to the surface circumstances and the decisions to address them that would be similar to those in a large urban society. So I “casted” the simulation with as rich a social assortment as I could manage for fifteen participants. There included an elderly couple (he a decorated WWI officer, she a mother of four who sustained a life-threatening injury in the sinking); a young non-Caucasian race newly-wed couple; a nurse, a burly athlete, a congressman/woman; a judge (who is a closeted homosexual); a famous scientist; a millionaire (who manage to save a necklace worth a fortune); a minister and his teenage daughter (who has leukemia); a beautiful B-movie actress; a young boy/girl of twelve who has sustained a life-thretening injury, and; an ordinary seaman from the crew of the ship.

In the beginning, I had little idea of how important seating position in the lifeboat would turn out to be. Seats were arranged roughly in three sections, forward middle and aft, with people in those sections facing one another. I had the intention of creating little groupings, or cliques. I kept couples together, and positioned the injured child between the nurse and the burly athlete, for protection. The congressman/woman was placed alone in the prow, and the ordinary seaman aft, where the ships food supply (called energy chips) was stored. I intentionally placed the sailor on a higher chair, making him the one person in the boat who could be most easily seen by everyone else. His role defined him as having no special nautical navigational skills. Nevertheless, I was continually surprised to find that at the opening of the simulation the rest of the people in the lifeboat almost immediately deferred to him and accorded him implicit authority. I speculate that this may have had to do with either the height of his chair, his position near the boat’s resources (where the person manning the tiller also would be), or just the fact that he was a sailor. All of this in spite of the fact that he is a racial minority. (It should be noted that all the participants introduce themselves at the beginning of the simulation, telling things about themselves that are indicated on “role” cards they are given. They are also given information about themselves that may be disclosed optionally, for example, the closeted homosexual, and the young girl with leukemia.)

Staying Alive

The simulation operates as follows.

There is no rowing since they are far from shore without navigational instruments, and it would needlessly expend energy. Energy is an important component of simulation. All persons, or the lifeboat in possession of ” three personal energy chips” that represent their last nutrition and hydration. It is important to mention here that a survivor must always be in possession of at least one energy chip, which they are living on, in order to remain “alive” in the simulation. This energy is the first to be expended, and these chips cannot be traded or given away. There are also thirty-three “boat energy chips” in a box behind the sailor that can be distributed and exchanged.

What drives the simulation is that there are potentially disastrous storms that arrive every 30 min. or so. The boat is considered to be overloaded, and hence a storm of high magnitude could potentially capsize it at all would be lost. So, some critical decisions must be made. However, the lifeboat might be “lightened” if some persons volunteer to go quotes over the side” temporarily (figuratively holding on to lines that are attached to the lifeboat) and returning after the probabilities for storm have been calculated. But there are risks and costs for such altruism. Going over the side costs extra energy because of the cold North Atlantic water, so I’m extra energy chip must be surrendered.

As in life itself, a lot depends upon probabilities. So a master probability table was constructed to handle this. [See, pubs-sim.webloc]. The Probability Distribution governs circumstances (with the role of a die) such as whether an imminent storm will be of sufficient force to capsized boat, or not, to the probability of whether a sick or injured person’s condition remains stable, worsens, or kills them, to the probability at persons “going over the side” will be eaten by . . .

Sharks

Since this was an exercise in the classroom and not a real life and death adventure in the North Atlantic, I needed to keep it interesting, and especially have devices where the simulation would not be ruined by people committing voluntary suicide so they could get out of the simulation. The answer––sharks. The rule is that all persons who perish, by whatever means (and we will see what that means below) must be put over the side, which of course attracts sharks. The more people who are “buried” at sea the greater the probability that anyone else in the water will be eaten by sharks. The sharks are an opportunity to introduce the notion that there are costs and uncertainties that attend all social decisions.

Decisions

The simulation involves some simple rules of decisions. First of all, Dr. Fate, the role played by the simulation “operator,” is the final arbiter. The “players” are allowed to ask Dr. Fate questions, but he does not have to answer. They may however ask to stop time to propose something that might be put to a vote of all aboard. A quick simple majority vote will be allowed, proposal voted up or down, and time toward the storm continued. A simple majority could be used for example to force someone to go over the side, or to deny them receiving and energy chip. So, it is possible with a simple majority to kill someone. Such proposals are rare, and are always voted down. I might note something interesting here, that is, it seems that players who tend to keep their mouths shut and not make proposals one way or the other, tend to survive more than those that are politically active in the simulation. I have had some students say in the debriefing that they would not propose something that would harm or kill another because the way things worked it could easily be turned against them (sort of a “don’t do unto others . . . “ mentality).

Social class

I was particularly curious about the role that social class might play in the decisions that were made during simulation. I recall that in the case of Titanic, a ship that was divided into different classes of service, people in Third Class were kept below when the ship was sinking, their stairwells even locked to prevent them from getting to the boat deck. However my students were roughly of all the same social class, so they were reminded that they were to employ the social position of their role to argue for decisions. Titanic was a ship that was divided, socially and spatially, to keep the social classes in their respective decks (which is of course the element in the James Cameron movie––love affair grows between lower class Jack and upper class Rose––that gives this fictional element dramatic impetus). In the simulation, privileged and underprivileged and up seated right next to one another. I’m always surprised by the willingness and ability of my students to make the most of an acting opportunity.

Deadly Force

All societies are susceptible to violent forces such as revolution, coup d’état, or acts of terrorism, so there needed to be an element, at least for the possibility of such force, in the simulation. This was accomplished by providing one of the survivors, the ordinary Seaman, with a (toy) revolver. He is instructed during the setup portion of the simulation to keep the revolver secreted and not to “employ it” before the first storm session is completed. He was also told that the revolver, once made public, could be thrown into the sea, get into another survivor, or used to shoot people who would be considered killed and immediately put over the side. In order to provide some positive use for the gun, it was also the indicated to him that he could “save” someone who had gone over the side and was about to be the victim of a shark attack by expending to rounds (of the 5) from the revolver to dispatch a shark. It also elect to keep the revolver a secret and hence it would never play a role in the simulation.

Lessons

The most important part of the simulation process was the debriefing that took place once the simulation was completed. Students who were in the room but not participants in simulation were also invited to give their input. There were always differences in different “plays” of the simulation, but there were some salient observations that seem to come up in all of them.

Think first, principles next, then panic. Perhaps it was because most place of the simulation were with students of government, public policy, and the social sciences, that there tended to be an initial appeal to norms of rationality. Despite the fact that I had stripped the scenario of virtually all types of information that might be employed to form decisions rationally, students would ask for, and Dr. Fate would refuse to supply, any information that might be helpful. Keeping them in this state would usually quickly force them to address normative issues and there would typically be appeals such as “we should resolve to try to save as many persons as possible.” I call this the Benthamite position of “the greatest good for the greatest number.” This was an easy position to take in the early phases of simulation when there was no evidence strain on resources. It is reported that on Titanic initially there was little alarm among many of the passengers. Some thought that putting women and children in the lifeboats was just a precaution and they would soon be returned once the “problem” of the collision with the iceberg was solved.

In simulation, the initial sequence of expressing noble collective principles to guide decisions begins to give way as resources begin to diminish, as decisions involve greater risks, even as some of the participants “perish” and a sense that “everybody is not going to make it” sets in. There is what I call a “crunch” in the simulation after decisions have been made and resources expended in order to avoid a storm that would swamp the lifeboat and kill all, that it is costly in terms of resources to reduce risk, and to reduce risk for the greatest number is extremely costly, and resources begin to diminish rapidly to the point, where if the situation in the lifeboat continues some very hard choices will need to be made as to who will receive the resources that remain period This is where group solidarity begins to break down, or groups with different positions become more combative, and for some a somewhat “Darwinian logic” gains expression.

Women and children first. And here, another frequent outcome is that the most vulnerable participants have less of a chance of survival. In particular, the injured elderly wife of the World War I military veteran, often does not make it and is the first to “go.” Arguments are often made that the injured youngster it is unlikely to make it, so “why continue to waste resources” on him/our. Often, some mounted a spirited defense of the child because it is young and has its life before it, unlike the elderly woman, and there was an occasion in which one student playing the child (a woman in this case) became “hysterical” when she was denied necessary energy chips to continue to survive, a tactic that proved successful.

It should be noted here that it was the intent that the simulation should make some survivors more vulnerable and in need of the succor and sympathy of those better off in order to survive. Perhaps this is the logic behind “women and children first” into lifeboats. To increase their vulnerability, the sick and injured were required to surrender two, rather than one, energy chip at each round. So, they were expensive to maintain despite the fact that their condition might kill them anyway. Perhaps, logic on Titanic was that the men, stronger and perhaps more fit than women, had a better chance to survive “going down with the ship” (in reality only a few men did).

Fate takes a hand. Another salient observation is people in the simulation would rather that fate took the hand in resolving some difficult decisions, rather than a human decision-making process. So, for example, as was built into the simulation, once a person who went over the side made an unfortunate role of the die and was “eaten by a shark,” it was lamentable, but it also relieved pressure on the diminishing resources. Similarly, the die was rolled for each sick and injured participant to determine if there circumstance had worsened. Two rolls of an odd number in succession and they were considered to have succumbed.*

The Gun and Jewels

The gun came into play in around one half of the simulations. It usually was an amusing surprise to the rest of those in the boat, often with immediate suggestions of “get rid of it.” It should suffice to say that a lot depends on who has been chosen to play the role of the ordinary seaman. There’s more that can be discussed about this matter than is allowed by the space, but a couple of interesting points can be made, neither of which I anticipated. In one instance the gun was used by the ordinary Seaman––and this surprised me––to “kill” 5 people in the boat. But afterwards, the remaining outraged survivors decided to vote in the majority to throw the murderous sailor over the side.** Ah, democracy!

And equally surprising employment of the gun occurred during a play of the simulation at a Hong Kong University. In this case the student given the role of the ordinary Seaman was a rather placid fellow, who I think in retrospect, my thought that the reason he was given the gun was that he was supposed to use it. In any event, at one point when things were going frustratingly in the third storm period of the simulation, he brought out the gun, threaten to use it on a particularly vociferous passenger, and then in a weak moment so the required ” bang-bang” and dispatched the passenger. As it happened, I subsequently let the room to visit the men’s room, and when I returned I noticed that the ordinary seaman was not on his highchair at the rear of the “boat,” but was sitting with the other students in the audience. When I asked one of the students what happened, he replied that sailor was so distraught after having made the decision to kill a fellow passenger, that he announced he was committing suicide, put the gun to his head, and said “bang-bang.”

The jewels however, even though they are “worth $1 million,” seem to have little effect in the simulation, not even a sufficient sum the purchase a couple of energy chips when the going gets rough. (In the film Lifeboat a diamond bracelet that belongs to the wealthy lady aboard is offered by her the use as a fishing lure.)

My simulation attempted to be a compression of much of what we have to deal with and decide about in our lives. It works to push the various issues of morality, rationality, and just plain luck, to the surface in a short period of time. And perhaps that is the reason why we remain so fascinated, so captivated, by the Titanic disaster. Because here was an entire society arcing across the cold North Atlantic, much in the same way that Earth arcs its way through the coldness of space, with everybody’s fate somewhat intertwined. We all have to ask ourselves what we might have done had we been on the Titanic, whether we were the wealthy Mr. Guggenheim, or some almost nameless, an immigrant in third class. What might we have done were weak Capt. Smith, or some officer, or some ordinary seaman? My simulation merely changes the circumstances to a microcosm; the same issues apply whether it is 1500 passengers or 15. Had not the Carpethia been in the vicinity that fateful night, the lifeboats of Titanic might have replayed the same drama again and again.

“What do we win?” I have been asked more than once in the follow-up discussion sessions. It’s an interesting existential question. What do we win in life? In a sense, our inevitable mortality means that we always “lose.” Is surviving tantamount to winning? Or is how we survived the way we win? One approach to addressing this question comes from the Titanic disaster itself. Aficionados of the subject will recall Mr. J. Bruce Ismay, the Chairman of the White Star Line who managed to get himself into one of the lifeboats and was rescued. Subsequent documentaries have noted the fact that Mr. Ismay’s reputation was eternally blackened by what was considered to be cowardly behavior, especially when there was so much selfless sacrifice.

The shark situation provides another mirror to the way things can happen in society. When things started to go downhill, economically, with natural disasters, or with revolution and war, as things get worse and more people die it often leads to even further death and destruction by way of revenge, moral decline, and lack of concern for human rights. The sharks are not a “them,” they are always, potentially, “us.”

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.14.2012)

*I have often wondered if this might be one of the sources of the human belief in a supreme being. How often have weird it said when someone dies, say prematurely or in an accident, that it must have been his/her “time,” or “God must have wanted to call him/her to him.” If God does the killing we are not to blame. (I should note that I do not bring up this point in the debriefings.)

**I wonder what differences possession of firearms aboard Titanic might have made. Surely there were firearms as part of the ships equipment, but these were also the days before homeland security in which it must have been possible for passengers to bring personal firearms aboard a ship. Were I one of those 3rd class passengers that they locked below decks as the ship was sinking and was in the possession of a firearm, I very likely would have found use for it to force those companionway gates open.