[continued from 88.3]

The rather odd story of Western heroism in the face if the Japanese conquest of Nanking is recounted in John Rabe, the true story of the German businessman in Nanking in 1937 – 38. German actor Ulrich Tukur performs in the title role of man who is sometimes referred to as the Oscar Schindler of Nanking. From the German point of view this film both somewhat rehabilitates, rather compensates, for the treatment that Rabe, a German businessman for Siemens in Nanking in the late 30s and a national Socialist who, when he repatriated was not well treated because he had contested with the Japanese occupiers of Nanking.1 Rabe was involved in the setting up of the security zone in the city, and personally risked his life confronting Japanese authorities and sometimes drunken, raping, Japanese soldiers. He is credited in many sources with having saved the lives of thousands of Chinese civilians. The 2009 German production, however, might also be seen by some as a subtle form of propaganda in its own right. Rabe himself was a member of the Nazi party and, although he managed to use the fact that Nazi Germany and Japan were allies during World War II as a means of negotiating with the general’s in charge of the occupation of Nanking, might not the casting of him in in this film be seen by some as deflecting attention from Germany’s wartime Holocaust atrocitie?. But it should not also go unremarked upon that the film also portrays far less heroic Nazi officials who cared for her lust for the fate of the Chinese. Moreover this is a film that was well-produced and, of some significance, was shot in Nanjing and employs German, American, and Chinese and Japanese actors playing their own national and racial counterparts.

The acting and directing in John Rabe are of very high quality, and it might be that the inclusion of American actor Steve Buscemi speaking quite good Mandarin (although the movie employs English, German and Japanese as well) was intended to garner some appeal to Anglophone audiences. But while there certainly is some violence depicted, the Japanese appear rather too tame in this film, and a scene in which girl students are required to strip in front if them in a search for a young soldier doesn’t seem to carry they sense of menace they exhibited toward Chinese women and girls.

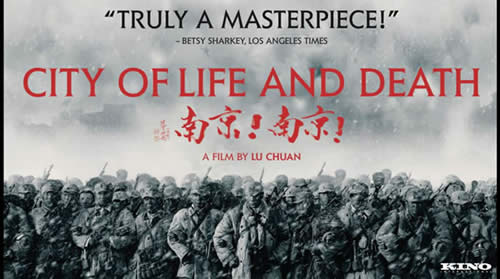

Far closer to that menace, and in gripping documentary detail, is Chuan Lu’s City of Life and Death (2009),2 a fully Asian production that contains far less character detail. Lu’s Nanking (shot locations in Changchun and Tianjin) exhibits all of the devastation of war, and deliberately reenacts the numerous methods ruthless Japanese employed in their executions of captured Chinese soldiers, including a mass machine-gunning of perhaps thousands of them near the banks of the river, groups of them tied together and buried alive, others incinerated in buildings in which they were locked, hanging, sparing the viewer only the contests that Japanese officers engaged in by summary beheadings with their samurai swords by only showing decapitated heads dangling from wires. The scenes, in black-and-white, rival the first twenty minutes of Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan.

Curiously, and apparently the reason this film received a lot of criticism in China, the main character is a Japanese soldier, Sgt. Kakodowa, (Hideo Nakaizumi) who is uncomfortable with all the horror, although not moved (even if he could be) to act in ways contrary to his orders. This semi-humanizing of the enemy, might have been a slight softening in view of the fact that Chinese movie censors are always lurking, and the government does have concerns about offending its erstwhile enemy, but contemporary lucrative trading partner. But that is just speculation on this writer’s part; I can barely get a good table at a restaurant, much less entrée into the inner sanctums of Chinese media and politics.

City of Life and Death comes closest to visiting Nanjing’s commemorative museum, or leafing through the stomach turning photographs—many taken by the Japanese themselves—of the atrocities in process, or their aftermath in the catalogs on the subject. Of the Nanking atrocities films it has the most authentic “feel.” It features only two rather unknown Western actors, John Paisley in the role of John Rabe and Beverly Peckous as Minnie Vautrin,3 almost no English dialogue, and so was most likely made for Chinese and Asian audiences. (Unfortunately, the English subtitles appear annoyingly about one line of dialogue behind the Mandarin being spoken.) Nevertheless, not much expense was spared in the realism brought to the battle scenes between the Chinese and Japanese soldiers, and subsequent atrocities.

Expense was also not an impediment in the construction of an elaborate twelve-acre set for Zhang Yimou’s The Flowers of War. In terms of its presentation of the Rape of Nanking, this film falls somewhere in between the others. Its high production values prove well worth the cost and Zhang, a director of considerable repute, eschewed the temptations of CGI for the sake of a visual authenticity worthy of the events portrayed.

But what lurks in the background is the nagging concern that The Flowers of War is a work of fiction (based on Yan Geling’s novel). With such glaring and gory reality the worry is that a roman a clef set on the Rape of Nanking might take things one small step in the direction of an eventual musical. The story is engaging and almost paradoxically and melodramatically heartwarming. However in terms of cast, Christian Bale, as an American mortician––perhaps too apt an occupation for someone in a place about to have nearly a third of a million fatalities in a matter of weeks––called to prepare a deceased priest at a school for young girls arrives coincident with the invading Japanese army of murderers and rapists. Initially, self-interested and self-preserving is gradually drawn into a situation of caring for their survival of the thirteen girls in school. Shortly thereafter, there arrives, unwelcome, but undeterred a like number of prostitutes fleeing their brothel down by the river. Although the gates are not opened for them, a scale the walls, enter the school church complex, but are relegated to its basement.

Bale dons the available priestly garb for his own survival and is soon being treated, as his behavior becomes more sympathetic and altruistic, and addressed by the students as “Father John.” The Japanese are unaware of the presence other prostitutes in school, but are keenly aware of the thirteen pretty, young virgins, want them delivered to serve as “comfort women.”4 Whatever this film’s weaknesses it can be credited with introducing a lovely and talented Chinese actress named, unforgettably, Ni Ni.

Like the Holocaust in Europe, committed by the Axis allies of the Japanese, cinematic interest in this subject might owe to the sheer mind-stunning incredibility of such horrific inhumanity. Like the Holocaust, the rape of Nanking took its “justification” in a racism that demeaned and dehumanized its victims, and at its most base expression of human sadism, the joy of cruelty by its perpetrators. In my own attempts to “ground” and “verify” these atrocities I have visited Dachau and Auschwitz, but walking the streets of Nanking strains one’s imagination for a sense of the horrors that occurred in them. Moreover, although the Holocaust of Europe remains well-documented and revisited in films and novels, the Rape of Nanking has been less remembered in popular media until, it seems, be economic emergence of China in the past three decades has rekindled an interest in one of the ugliest chapters of the long history of that nation.

Bit parts for Western box office names might be the current marketing fashion for Chinese directors mining the rich and variegated ore of China’s mega-disaster history of the 20th Century. War, revolution and foreign invasion often conjoined with, or were exacerbated by, natural disaster, and filmmakers with innumerable “extras,” expanding production budgets, legions of CGI technicians, audiences increasingly prepped by violent video games, and prospects for lucrative foreign distribution, could hardly resist. Xiaogang Feng’s Yi Jiu Si Er, released as Back to 1942 (2012) to U.S. audiences employs that formula to good effect, recreating the horrors of the Henan province famine of that year that took at least three million lives. The director pulls no punches in calling the meteorological fate, the Japanese military and the callousness of the KMT to account. The death throes of the old social order is prefigured in downfall of a wealthy landlord who loses everything and is left only with the “seed corn” of a orphaned girl to try to begin again. Brody’s role as journalist Theodore White gives the disastrous events its “American eyes,” but Robbins as an accent-challenged Italian priest seems a gratuitous box office enhancement feature. There appears to be no “whiteface” counterpart to Hollywood’s “yellowface.” Xiaogang Feng earned his Chinese disaster credentials and facility with a broad cinematic canvas with his earlier (though later historically) Aftershock (2009), bringing to the screen the Tangshan earthquake of 1957, another Chinese disaster whose real occurrence of which the West was almost completely unaware.5

China’s 20th Century trilogy of tragedies—natural disaster, foreign invasions and internal ideological struggles—would seem to aptly absorb much of its cinematic interest as they have not only shaped and prefigured much of its recent history, but also is now out of experiential range of its current generation. This has only recently become possible for Chinese film makers. Ian Buruma recounts the following story:

When I was a student of Chinese in the early 1970s, we had to read long and tedious articles in The People’s Daily denouncing the Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni. As a well-known fellow traveler, Antonioni had been asked to make a documentary film in China during the Cultural Revolution. The resulting movie, Chung Kuo—Cina (1972), was by no means unsympathetic. But Antonioni had made the mistake of showing Chinese faces that were unsmiling, and he could not disguise his aesthetic appreciation of traditional culture. He tried, despite severe restrictions, to present what he saw as the truth. This was regarded as a hostile act. The film was banned, and the director was branded an anti-Chinese counterrevolutionary.6

By contrast, what seems to absorb, if not obsess the counterpart generation of American moviegoers, who come from relative peace, comfort and stability, is fantasy/apocalyptic fare of space-alien invasions and the consequences of material excess and environmental degradation; but imaginary tragedy is preferable to the real thing.7

[To be continued]

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.11.2014)