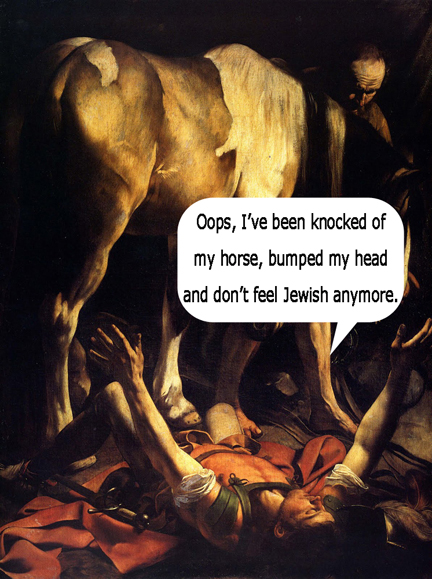

“Conversion of St. Paul,” Caravaggio (1600).Basilica of St. Mary, Rome

The great foundational myth of Christianity, and the Roman Catholic Church, is that it was the project of Jesus Christ (and his Dad). In fact, Christ (who, we have already established was not known by this Greek name) was only the leader of a rebellious sect within Judaism that seems to have pissed off the Jewish establishment and was an annoyance to the Roman overlords of Palestine.

It was another Jew, Saul, a Pharisee from Tarsus, in what is today Turkey, who really got Christianity going. He might even have been the first to use the term “Christians” to describe Jewish converts he encountered at Antioch. But that was a little later. Saul, who originally would have identified himself as a “tentmaker” on his Facebook or LinkedIn page, figures in what was a rather quirky beginning for one the three great Western faiths. But his religious preferences started out persecuting the followers of Christ, and was, as reported in Acts of the Apostles, apparently was complicit in the stoning of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr.

Saul never met Jesus. Well, not in a formally-introduced sense. The story is (and paintings by Caravaggio and Parmigianino illustrate) that Saul was on his way to Damascus when he was knocked off his horse by a blinding light and heard Jesus ask him why he was persecuting him. Somehow Saul took this to mean he should change his name to Paul, change his ways and start a new religion. Paul was technically not an apostle, but is sometimes regarded as the new “12th” (since Judas’ departure); he did meet Peter and James, Jesus’ brother. He was supposed to be the evangelist to the gentiles (with Peter handling the Jews), but apparently spoke to whoever would listen.

“Paul was a city person,” write religious studies professor Wayne Meeks, elaborating:

“The city breathes through his language. Jesus’ parables of sowers and weeds, sharecroppers, and mud-roofed cottages call fourth smells of manure and earth, and the Aramaic of the Palestinian villages often echoes in Greek. … Paul was among those who depended on the city for their livelihood. He supported himself at least partially, by work “with my own hands”—making tents, according to the book of Acts… The urban handworkers [he evangelized] included slave and free, and a fair range of status and means, from desperate poverty to a reasonably comfortable living, but all belong thoroughly to the city. They shared neither the peasant’s hospital fear of the city nor the aristocrats self-confident power over both polis and chora. The author of acts hardly errors when he has Paul boast to the Tribune, astonished that Paul knows Greek, that he is “a citizen of no mean city.” [Acts 21:39][1]

Thus, Paul was making a break with the long and deep tradition recounted in the Old Testament of the Hebrews as a pastoral-nomadic people, and his rather un-urbane fellow apostles in the New Testament.[2] This is an important break in at least a couple of respects. He was certainly no screaming liberal, but Paul did write to the Galatians he saw no difference between slaves and freemen, and males and females: “You are all one in Jesus Christ.” Makes one wonder what the hell happened to early Christian thinking. But this doctrine was also a separation from the Torah. Is there in this doctrine and in the divided missionary responsibilities of Paul and Peter, and in subsequent references to Jews and gentiles, a parting of the ways between Jews and Christians and the formation of the roots of a Christian anti-Semitism. Moreover, is this where we begin to see the de-Jewification of Jesus, and the eventual insurgency of Christian anti-Semitism?

In a way Paul is as interesting a study as Jesus. Jesus, half man/half god; Paul, from persecutor to evangelist to what theologians still debate as half Jew/half Christian. Paul did give contradictory messages (if he indeed was the author of everything over his signature) on such topics as circumcision[3] and obedience to secular authority, as some students have alleged, depending on whether he was speaking to Jewish (wasn’t this Peter’s job?) or Christian audiences. Where, and at what point, does Paul transit from Jew to Christian, and by extension (and more importantly) does Christianity separate from its Jewish roots, is an ongoing issue among students of early Christianity.

Paul and Christian Anti-Semitism

When Paul exempted Christian proselytes from the law and from circumcision, he thereby made a crucial irreconcilability between Judaism and the new Christianity and became known not only as the Apostle of the Gentiles, but also among his fellow Jews as the “Apostate of the Law.” It opened the door to such abominations as deification of Christ, the cult of the Virgin Mary ad their images in Churches. Paul and other missionaries continued to preach in the synagogues, but the gulf widened between church and synagogue. Christianity birthed in Judaism and influenced by it, ceased to be Jewish in language and outlook. This threatened Judaism and, as the new religion gained converts, the older faith closed ranks and regarded the Christians as heretics.

The war of the Christian Church against the Jews began in the 4th C when Church Fathers commenced relentless attacks on those Jews who stubbornly refused to accept Jesus as Messiah. Despite their belief that Christ’s death was necessary and predestined, they denounced the Jews it wasn’t much of a stretch for them to begin denouncing Jews as clamoring for the crucifixion of their (whose?) Messiah.

Paul’s teachings might have made it possible for a detente between the early Nazarene movement and its fellow Jews as there were not any great conflicts between the two. But with the emergence of the early Catholic Church, and as the teachings of Jesus formed into a theological doctrine, the rift widened.

The Church system became highly organized with authority, creeds, and a canon of scriptures. The religion of Jesus was replaced by a religion of blessings to be received only through sacraments, administered only by priests. By the 4th C Church clergy, organized on an hierarchical basis of deacons, presbyters, and bishops, were well established and “lorded” it over the laity,” and buy the end of the century the “bishop of Rome” (a still used title) was calling himself “Pope” and “head of the Church.”

Now the breach was nearly complete. (Jewish law of circumcision and conflation of ethnicity and faith also contributed to the separation) and with the growth of Church theology—never mind that the center of it was a Jewish rabbi—

Church Fathers were to become increasingly obsessed with Jewish culpability for the death of Jesus—never mind that without the crucifixion the Church would not have its foundational dogma of resurrection, forgiveness and salvation! (If you ever need a definition of crazy, feel free to use this.) Such were the connectives for Christian anti-Semitism and Church fathers like Origen (185-254 C.E.) were declaring that “On account of their unbelief and other insults which they heaped upon Jesus, the Jews will not only suffer more than others in the judgment which is believed to impend over the world, but have even already endured such sufferings.” Here he refers to their disaspora engendered by the Romans in 70 C.E. “For what nation is in exile from their own metropolis, and from the place sacred to the worship of their fathers, save the Jews alone? And the calamities they have suffered because they were a most wicked nation, which although guilty of many other sins, yet has been punished so severely for none as for those that were committed against our Jesus.” And so the Jews as “Christ killers” was handed down throughout succeeding generations in Christendom. [4]

Catholic Church anti-Semitism ended up being promulgated from its highest offices.

Pius VII (1800–1823) reestablished some of the more odious conditions for Jews in the Papal States, including ghettos. Kertzer goes on to argue forcefully that far from resisting the rise of modern anti-Semitic ideas, some Catholics (including diplomats, priests, journalists, and writers) helped promulgate many anti-Semitic slurs and libels about Jews and their “Talmud-based religion”; and popes lent them the sacred imprimatur of the Vatican. . . . One of the characteristics of this form of anti-Semitism is the idea that Jews are not just religiously and culturally different but racially alien. . . . [I]t was the papacy—along with many of its foes—that helped to monstrously dehumanize the Jews, that imagined them as a separate people and race, not just practitioners of a different religion, and that stimulated followers to view them as different, treacherous, and iniquitous.[5]

This is hardly the end of the story with Christians and Jews. According to Protestant Christian believers in the “rapture” the Jews will get one last chance to accept Jesus as their Messiah at the “end times” when Jesus himself will return to earth to collect the “saved” who have accepted him as their lord. They better not blow it because the earth will be destroyed inn the rapture and he Jews will probably be sent to someplace where there will be no international banking or media for them to control and only pork chops to eat.[6]

But let’s get back to the guy who seems to have set this all in motion, Saul/Paul. Writing about “Catholics and Jews: The Great Change”[7] Catholic author Gary Wills, states that several theologians “began to focus on one passage in the New Testament, the genuine letter of Paul to the Roman [that] said that “God has not rejected his people.” God could not do this, since his calling of them is “not subject to second thoughts” (ametamelēta), and “the whole of Israel will be saved.” Paul says that how this will happen is mysterious, but believers in Jesus are branches grafted onto the root of Israel, and the root cannot die while the branch lives.”

Great change? Right. “Mysterious.” Horticultural metaphor. That’s cool. Really ought to help.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 26.03.2016)

[1] Meeks, Wayne A., The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul, (New Haven: Yale, 1983), P. 9.

[2] Indeed, much of the Bible is laced with anti-urban sentiments. See, Clapp, J.A., The Roots of Anti-urbanism, The Institute of Public and Urban Affairs, San Diego State University, 1978.

[3] This alone would be a good separation point for me. Thank you, I’ll take the faith that you can join without having to submit to some guy slicing an inch of your dick.

[4] There was also speculation that Jews might have aided and even instigated the early Roman persecution of the Christians in the early days of Christianity.

[5] Kevin Madigan, “Getting the Jews and the Vatican Wrong,” New York Review of Books, November 21, 2013

[6] Think this is weird? Have a look at my Dragoncityjournal.com posting 4.7 “And they shall be led into the land of the corn”

[7] New York Review of Books, March 21, 2013, reviewing From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933–1965 by John Connelly, Harvard University Press