It only took me a couple of minutes to discern that she had not even read my book. The attractive, business-suited Chinese woman sitting across from me at the Pacific Coffee in Hong Kong represented an investment group from the mainland that my agent who arranged the meeting said might be interested in producing the screenplay I had derived from my novel. It was also clear that she had not read the screenplay. It hardly mattered, since as soon as I got to that point in describing the story that featured a protagonist that was a local Hong Kong prostitute the woman preemptively responded that her company would not be interested in underwriting a film with such a negative portrayal of Chinese womanhood. I never got to the point in my story that my protagonist ends up being an admirable, if not heroic, example of self-sacrificing Chinese motherhood. Unfortunately, I heard that same prudish-“face-saving” attitude from other potential Chinese investors.

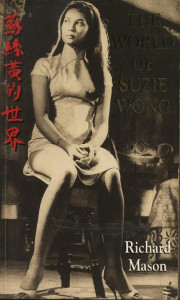

It was not an unfamiliar refrain to me. I had heard it from Nancy Kwan, the actress who played the lead in The World of Suzie Wong, the 1960 movie that had inspired my novel. Nancy is largely celebrated for being an actress who not only well represented Chinese pulchritude, but also for having opened a path for subsequent Chinese actresses to receive lead billing in English language feature films.[1] Nancy had received criticism from some Chinese for glorifying the role of a Wanchai prostitute.

I must admit that in my book, For Goodness Sake, a Novel of the Afterlife of Suzie Wong, I do draw some metaphoric comparisons between prostitution and Hong Kong. But in doing so I don’t think I was breaking any new ground. Here, for example, is what Ian Buruma recently wrote in The New York Review of Books:

“Great cities have often been compared to whores. The Whore of Babylon, mentioned in the Book of Revelation, may have been a metaphor for imperial Rome, or possibly Jerusalem. Juvenal’s satirical poem about Rome, written at the end of the first century AD, conjures up the lascivious image of Messalina, Emperor Claudius’s wife, as a symbol of urban depravity. At night, the “whore-empress” made straight for the brothel, “with its stale, warm coverlets,” where “naked, with gilded nipples, she plied her trade….”[2]

Buruma was reviewing an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, September 22, 2015–January 17, 2016, Splendours and Miseries: Images of Prostitution in France, 1850–1910, that includes a number of paintings related to prostitution in Paris. So I at least was putting Hong Kong in the rather prestigious company, if somewhat salacious repute, of the likes of Rome and Paris. And Ms Kwan was at least linking her hometown with the gallery of famous urban prostitutes with a golden hearts such as Irma La Douce, Melina Mercouri’s Ilya of Piraeus, Aldona, in Man of La Mancha, Fantine in Les Miserables, Mighty Aphrodite, Julia Roberts’s Pretty Woman, and many others. Hong Kong’s Wanchai shared with many other cities a locus known as a yoshiwara, red light district, De Wallen, Patpong, or the like.

Prostitution has been related to cities almost from the beginning. Probably no theme is more influential in the Judeo-Christian view of the city that the Augustinian notion of the City of God versus the City of Man. Cities achieved a poor reputation early in Biblical history by virtue of their association with Cain, who, after murdering his brother, forsakes the protection of God for the protection of the city. However, the association with homicide is only the beginning of a representation throughout the Old Testament of cities and city life as somehow being at odds with divine purposes. We all know the story of Sodom and Gomorrah (and the incest that followed it). The Bible is full of prostitution, or its equivalent, and its compilers in the early Roman Catholic Church were not shy about using it to their narrative advantage, as in the case of the sadly mis-characterized Mary Magdalene.

Although, as Buruma states in his review, “. . . deceitfulness and greed being the twin vices commonly associated with city life . . . .” and “Prostitution, in its many manifestations, grew exponentially with the rise of the modern city,” we would be mistaken to assign the blame for this universal human practice to urbanism. True, cities provide the market, the medium of exchange, and the anonymity for prostitution, but in this writer’s regard, it is more appropriate to blame the Bible, not the City, for its scriptural contradictions, twisted morality, and mostly its misogyny, for placing women in circumstances that, in reality, are far more sinister than their depiction in the movies. And not just the Judeo-Christian tradition; check Afghanistan, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.

Sure, there is prostitution in cities; but if you want an argument from me I will maintain—and prove—that cities have done much more to liberate women from the oppression and gender confinement that for most of human history has restricted them to roles that, if they aren’t strictly defined as prostitution, are a form of social servitude and sexual enslavement that more than approximate it.[3]

I mean in no way to glorify prostitution; it is, despite the fairytale bullshit of movies such as Pretty Woman, a dangerous and inhumane “profession” on several levels. But, as an urbanist, one of the things that attracted me to the story of Suzie Wong (other than the obvious physical beauty and charm of the woman who played her in the movie), was the way n which the city provided a context in which an illiterate young woman, deprived of her virginity by rape and unable to take an excepted place as a Chinese wife, was able to ply her wits and her physical beauty to some economic advantage, something that would be all but impossible in village or rural Chinese society. And the city, as it historically has always offered the dream of something better of possibilities that girls in tradition-bound world societies are not likely to even imagine.

I was captivated by Suzie Wong’s pluck, her daring to dream that despite the work circumstances forced her to do, she would someday meet the man who would be her “first.” In my book about her “afterlife” I gave her an even greater redemption—motherhood. This is something that is revealed late in my story of her, something that I never got to explain—if even it would have been worth the effort—to that woman to whom I was pitching my screenplay. Had I been allowed to get to the point where I could say that my story was one that celebrated what could be regarded as the finest attribute of a woman, Chinese or otherwise, perhaps she would have seen the prospect of a Chinese motion picture with a depth and inspiration that would deviate from the ninety-percent of Hong Kong crap that is mostly inane romance or martial arts. But I am not going re-write my script. as “The Kung Fu World of Suzie Wong.”

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 12.27.2015)

[1] See my review of a book on Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong [32.3]. See also, Arthur Dong’s excellent documentary Hollywood Chinese (2007).

[2] December 17, 2015, Vol. LXII, No. 20, P. 44. The Juvenal reference is to The Sixteen Satires, translated by Peter Green, (Penguin Classics, 1999)

[3] See, Clapp, James, This Urban Life: Writing About Cities for Multiple Media (Bamboo Books, 2005) Ch. III.2, “City Women.”