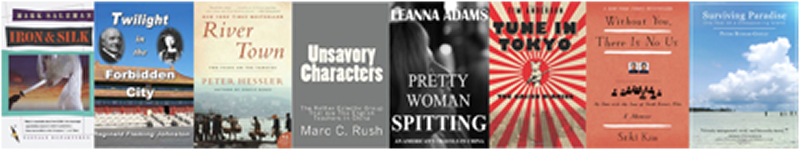

A multiple book review essay on:

-

- Iron and Silk (1987), Mark Salzman

-

- Twilight In the Forbidden City (Revised 4th Edition, 2009) Sir Reginald Fleming Johnston

-

- River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze (2006) Peter Hessler

-

- Unsavory Characters, The Rather Eclectic Group That Are The English Teachers In China, Marc. C Rush (2010)

-

- Pretty Woman Spitting (2012), Leanna Adams

-

- Without You There Is No Us, Suki Kim (2013)

-

- Surviving Paradise, Peter Rudiak-Gould (2009)

- Tune In Tokyo: The Gaijin Diaries, Tim Anderson (2011)

Jimmy, a former graduate student of mine from Bombay, occasionally writes to me about pedagogical matters from the college in China where he has been teaching English for the past few years. Unfortunately, his recent missive was on a subject the specifics of which were outside of my experience, i.e. what should be done in the matter of students using their cell phones during class. Even Chinese students from the poorer regions seem to possess what, in my days as a university student, only existed on Star Trek and, while cell phones came into popularity at the end of my teaching career, I never encountered by Jimmy’s dilemma, even when I have lectured to Asian students. He apparently just can’t seem to get them to turn the damn things off when they are in class and there don’t seem to be any administrative rules there to help him out. In these days when almost any photo of a classroom in most universities shows student desks displaying laptop computers or an iPads technology seems to be outpacing the pedagogical response to it, and classroom decorum.

I have taught other subjects—but not Engrish—in Asia. But, I know a couple of people who have, have read a few books on the experience, and can risk some cautious(?) extrapolations from my own Asia teaching and lecturing experiences.*

English, as we have been told many times, is (or has become) the lingua franca of the “globalized” world. Most scientific journals are in English, the international airlines use it, it dominates the Internet and subtitles in movies. Everybody, from the aspirant wheeler-dealer in international business to the Bangalore customer service rep (faking an American accent), to the Russian or Cambodian cutie looking to snare a nice wifely sinecure from some guy in the west [she loves me] needs reasonable fluency in English. Hence, it is a rather (too) easy matter for a “native speaker”** to secure a post teaching grammar, business vocabulary and maybe a touch of lit of it in foreign countries, especially Asia.

The first “English teachers” in East were the English, with their empire “on which the sun never set.” The raj in India, and then colonial outposts through Indochina and Hong Kong. But current aspirant English teachers are unlikely to encounter in a photocopied flyer at the student union, or on a web site, a posting like that taken by Sir Reginald Fleming Johnston, the English tutor of Emperor Pu Yi, the last Manchu ruler of China. Many will recall that Johnston was played with a stuffy self-possession by Peter O’Toole in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor. One might get a chance to tutor the kids of a contemporary Shanghainese tai pan, or the spoiled brat of some Comrade Mickey Mao living in Zhongnanhai, but it’s a slim chance. Johnston, who was fluent in and wrote and translated Mandarin Chinese, as well as the British-accented English that was more sought after in his day, tutored the occupant of he Dragon throne almost right up to his abdication and remained in China, with a stint kin Hong Kong, in a British administrative capacities for many years after.

Just as unlikely is today’s foreign language lao shi to encounter the degree of respect accorded the Johnston in his tutorial responsibilities. In his book Johnston quotes from Dr. W.A.P. Martin: “In no country is the office of teacher more reviewed. Not only is the living instructor saluted with forms of profoundest respect, but the very name of teacher, taken in the abstract, is an object of almost idolatrous language. On certain occasions it is inscribed on a tablet in connection with the characters for heaven, earth, prince and parents, as one of the five chief objects of veneration, and worshipped with Solomon rights.”***

It was not long after Kissinger and Zhou were exchanging courtesies from heavily-upholstered chairs with antimacassars that English was to become an accepted, if not necessitated, subject of study in Chinese educational institutions. Soon students were collecting on the Bund in Shanghai to practice their pronunciation and mimic accents from American tourists.Before long, “native English” (not Engrish) teachers were finding their way into Chinese universities to prepare them for reading assembly instructions for American products and hacking into American data bases, or to head off to graduate studies at Berkeley.

Iron and Silk, the first account I read of teaching English in China is the account of the first job of young Yale Chinese Literature grad Mark Salzman. Salzman was clearly not taking the assignment because there was not a suitable post in some more preferred field of work. A student of the language, calligraphy, and even the martial arts (wu shu) he was well on his way to becoming a China hand. In 1982 was teaching English to students and teachers at Hunan Medical College in Changsha. He presents a sympathetic and often humorous episodes of his experience as teacher, but also a student of a si fu (master) of China’s martial arts, with dramatic features that he subsequently reworked into a film that could serve as a positive model for other English teachers in China. Salzman went on to marry a Chinese-American woman (not the one on the bicycle in his book) and to produce and play in a film based on his book.

Peter Hessler, who studied English literature at Princeton came by his time when he joined the Peace Corps in 1996 and was posted to China for two years at a teachers college in Fuling, a small River Town near the Yangtze River in Sichuan Province near Chongqing city. Responsible for all aspects of English Hessler concentrated mainly on literature. As with others who have taught in China he noticed the unavoidable tendency for foreign literature to become conflated with politics in a country where education was subordinate to political loyalty. To “ardently love the Motherland, support the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership, serve Socialism’s undertaking, and serve the people” was printed on the red identity card they all carried as the first of eight “student regulations.” Hence, they might disrespect Hamlet for his lack of leadership and being overly sensitive or, even though Robin Hood served the poor, he would need to be arrested for breaking the law.

But the intrusion of politics and ideology into the classroom exposed other contrasts between American and Chinese education. “As time went on it almost depressed me, he wrote. “The Chinese had spent years deliberately and diligently destroying every valuable aspect of their traditional culture, and yet with regard to enjoying poetry Americans had arguably done a much better job of finishing hours off. How many Americans could recite a poem, or identify its rhythm? Everyone of my Fuling students could recite at least a dozen Chinese classics by heart—the verses of Du Fu, of Li Bai, of Qu Yuan—and these were young men and women from the countryside of Sichuan Province, a backwater by Chinese standards. They still read books and they still read poetry; that was the difference.”[p.42]

As with all foreign teachers Hessler is necessarily a student as well, with much to learn of a five thousand year old culture. He achieves facility with the language and which perhaps entitles him to his Chinese name, Hé Wei. His tenure in Fuling also transected “interesting times,” in this case the death of Deng Xiao-ping n 1977, that was followed by economic changes and growth rates that in the space of three decades produced the world’s second largest economy.

___________________________________

©2015, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.22.2015)