There were seven screenwriters on Casablanca. Chances are that at least one of them had a romantic experience in Paris that resulted in Bogart’s doleful line to Bergman that “we will always have Paris.” Only Paris knows how many romances, fleeting and eternal, fatal and fated, doomed or destined, have played out in its streets, cafes and rooms with a view of the Tour Eiffel or Notre Dame. Only Paris recalls if Abelard once moaned to Heloise, or vice versa, with a bittersweet regret, “we will always have Paris.” Only Paris could recount the love made in palaces and garrets, in the bois or the Metro, on rooftops or beneath the Opera, while revolution raged or the Wehrmacht jackboots echoed in its cobbled streets. “We will always have Paris” is, in the end, because we can only retain and possess Paris in memory, because Paris will not always have us, is a melancholy admission that we only have our moment, our “time,” with Paris. We will be replaced.

So be it. But the Paris romance movie is such an established genre that it can easily embrace subsets of surprising specificity. There must be a bottomless inventory of producers, writers, and directors that have had or know of a Rick and Elsa romantic encounter in Paris. I have had a few, each wonderful and memorable in its own way, but they are only obliquely, in the personal experience through which one always views art, exposed in this essay. Anyone who has been in love in (and with) Paris probably has a Paris movie in them, apparently even that sub-set that we might charitably call “aging academics.”

In 2013 the minor genre that could be labeled “retired professors try for that old Paris feeling one last time” received three additions.* In somewhat ascending order of cinematic quality they begin with Le Weekend, in which superannuated British professor Nick (James Broadbent) brings his wife Meg (Lindsay Duncan) to Paris to try to re-spark their moribund marriage. Unfortunately, Paris does not seem up to the task of romantic rejuvenation of their honeymoon there decades earlier. Or perhaps the city is as indifferent to the bickering and juvneile pranking of this couple as we are likely to become watching this querulous duo fail to overcome with strained dinner conversation and joyless sex some long past infidelity of Nick’s and latent flirtatious urges in Meg. I turns out that it is not the fault of Paris that Nick’s academic career fizzled out quite early. This we learn from an encounter with Nick’s old college classmate and admirer, Morgan (Jeff Goldblum), who is a successful writer living a cavalier Jeff Goldblum-like life with a young wife in a spacious Paris apartment. At a dinner party at Morgan’s Nick cathartically blurts out his disappointments and the news that he is likely losing his teaching post. In the end Morgan might be a deus ex machina for his old friend, but it is clearer that this couple probably needs one another, however unpleasant that may be, more than a weekend in a Paris that seems irrelevant in this movie.

Elsewhere in Paris in the same period another Matthew Morgan (Michael Caine) is mourning the recent death of his wife. The opening scene is her deathbed scene. In Last Love we don’t know whether the title refers to Morgan’s last (final) or Mrs. Morgan, or the possibility of a new encounter, as she (Jane Alexander) briefly reappears, as imagined by him, to comfort and counsel her husband at various times in the film. In between, aging retired professor of philosophy pads lugubriously around a beautiful apartment that many would kill for or heads to the cemetery with a sheaf of lilies, until on the bus one day he meets dance instructor Pauline (Clémence Poésie), who is young enough to be his daughter. Something ambiguous (something different than the flat lunchtime relationship of indeterminate purpose between Matt and a pleasant middle-aged French woman) forms between him and Pauline, who we learn lost her father at a young age.

Refreshingly, this is not tourist Paris but the Paris of working-class people riding buses, sitting on park benches and, taking classes in line dancing. But Matthew seems to be there only because it was his wife who truly loved the city. In their many years living there, and in their country home in St. Malo, he is not bothered to learn the language. (Gratuitously, the screenplay has Michael Caine as an American professor, an unfortunate decision if one is casting British actor with a distinctive cockney accent.) He fails at an attempt at suicide, not having taken a sufficient number of sleeping pills, which brings Pauline to an encounter with the professors children, who arrived from America with not the most noble sentiments. His daughter is mostly concerned with her inheritance, and with getting some Paris shopping done before leaving the following day. This is not a happy family and, when Matthew takes Pauline for a visit to his St. Malo house he confesses that he never really wanted a family and that was a concession to his wife. He is disclosing, but not self reproachful, that he was and is not a “good father.”

Predictably, but wrongly, Matthew’s children see “golddigger” in the motivations of Pauline, not realizing that it is perhaps only her ambiguous relationship with their father that is keeping him alive. The daughter returns home, but the son, Miles (Justin Kirk), remains in Paris for a time as we he has somewhat of a reproach mom with his father in which we, and Matthew, also that he is being divorced by his wife. Unfortunately for the movie this set up pays off precipitously when Pauline throws herself into the arms of Miles. It is not an implausible dénouement for a movie set in Paris, but it occurs all too conveniently and precipitously.

Aging professor number three is English Lit prof Doug (Gabriel Byrne), is on a train bound from Calais and Paris in Just a Sigh. He is returning to France for the funeral of a former classmate during his student years in Paris. Doug has also gained the fascination of Alix (Emanuelle Devos), an actress also destined to Gare du Nord and an audition for a television role. It is dramatic “strangers on a train” premise that is almost clichéd. But it is why Alix, young and beautiful, decides to crash the funeral in pursuit of the older, graying, taciturn Doug that takes engages us. Doug appears to have no idea, and even Alix, with a boyfriend of several years that she can’t seem to get on the phone, does not seem understand her compulsion. She follows dog from the church to a bistro, to his hotel and, after very little exchange of interests or information, and up in bed together. It is in the pillow talk that we discover that Doug is a professor with four children (wife is not mentioned) back in England, his relationship to the deceased is kept vague beyond open (again) a reference to Her having been a former classmate with achievements he might envy.

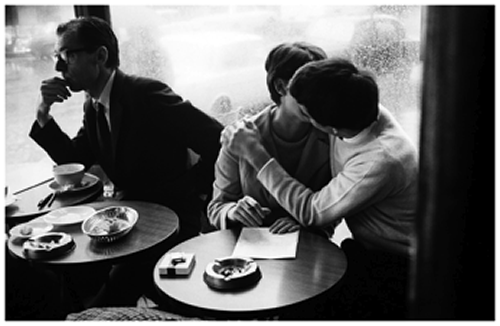

Their bed play might be a “one off” when Alex leaves to visit, reluctantly, her older sister to borrow some money. She is also scheduled to return to Calais for the play that she is in. But after a row with her sister and more failed attempts to reach her boyfriend she returns to Doug’s hotel for more love-making and pillow talk, during which it is disclosed that she is a couple months pregnant. Although pressed for time to return to Calais they spend the day together and here the audience is treated to a Paris brimming with life and activity, with African bands and dancers, Left Bank cafés with patrons spilling into the streets. The urban joie de vivre appears to move the rather introverted Doug to declare he would like Alix to return with him to England. Her decision remains in question right up the Gare du Nord, from which she must return to Calais. The suspense is reminiscent of many dramatic train station departures, such as that between Audrey Hepburn and Gary Cooper in Love in the Afternoon (1957). But Alix boards just before the train departs, leaving, perhaps for the best, Doug on the platform.

In the final analysis Paris in these movies seems to be a city that is indifferent to our emotions and sentiments. We may bring to it the lore, from previous film, literature and song, that it possesses a special magic that makes “hearts light ad gay,” but it is only a grand stage for us to play out our amours. And for old professors who have known love in Paris it is the memory they are in love with, not the city. Cole Porter probably said it best.

I love Paris, why, oh why do I love Paris

Because my love is here.

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 10.27.2014)