This is a slightly revised paper that I presented at the National Meetings of the American Institute of Planners, Atlanta, Georgia 1973,

Introduction

Probably from the time of the very first primitive urban settlements along the banks of the Nile and the Tigris, Euphrates, the Indus and Yellow rivers, those very first urbanites already had some misgivings about urban life. Those reservations and doubts might have been based in some primitive religious musings about their beginning to separate themselves from nature, some murky existential doubts, perhaps something in the incipient division of labor, or may be just in the emerging tendency of urbanites to be, with every practical success, dissatisfied with the status quo from the knowledge that things could be still better. We will never know for certain, but we do have some ancient writings that indicate that anti-urban sentiments begin to appear very early in the history of cities.

We also know that since the advantages of urban life were discovered some 10 or 12 millennia ago that, with fits and starts, urbanism has shown itself to be the preferred way of life to the point where in recent decades the population of the world has become more urban than rural and is likely to continue in that direction. So why, we might wonder, when there has been this pronounced movement from world and pastor role to urban, has there been a prevalent strain of anti-urban sentiment in our species? What is the source of our urban discontent?

This paper concerns itself more with the clarification of a hypothesis rather than its proof. It is primarily concerned with the notion that the subtle transmission of entire urban sentiments from generation to generation might occur in the most simple and insidious ways. It suggests that anti-urbanism may appear in narrative themes that are presented to us early in the formation of our ideas and imaginations, and that that preparation might make it easier for us to accept such sentiments when they recur in other literatures.

The idea for this paper came from the very simple and common activity of many apparent of reading bedtime stories to their children. In this case, the story I read to my daughters was one that had probably been read to children for millennia, Aesop’s fable of the city mouse and the country mouse. Perhaps as an urbanist I was slightly more sensitive to the anti-urban character of this story, which led to searching among other children’s literature with an eye sensitive to—where it occurred—the portrayal of cities and urban life in children’s stories.

But first let us examine some of the statistical information related to the prevalence of anti-urban attitudes among contemporary urbanites.

Opinion Polls

The preference for not living in cities, which is one index of these sentiments and attitudes, is rather consistently reflected in surveys of housing, neighborhood and general locational preferences. For example, a survey reported by Time Magazine [1] several years ago states: “State of the Nation’ is that the majority of Americans yearn to escape urban areas not for suburbia, but for the truly open spaces. While only one out of three Americans now lives in towns, villages, or rural areas, more than half of the poll sample said they would prefer such a setting. That figure is swelled by the ranks of black city dwellers (70%) who want to move out.” Conclude the editors: “The figures suggest that if American people could follow their inclinations, the population of our cities would be cut in half. The proportion of suburbanites would remain the same. The proportion enjoying country life would more than double, from less that two in ten to almost four in ten.”

A 1968 Gallup poll [2] indicated that only 18 percent of the respondents expressed a preference for living in central cities; 25 percent favor the suburbs; 29 percent opt for life in small towns, and “. . . 27 percent actually said they wished they could live on a farm.”

As far as future housing consumers are concerned, surveys of American youth reflect these strong preferences for exurban living. A recent poll of students and non-students rendered the following breakdown of locational preferences.[3]

“In which type of place would you most like to live?”

Student Non-Student

Large city 11.4 14.2

Suburb 24.5 17.8

Small city or town 34.8 39.2

Rural area 26.1 28.5

No answer 2.2 0.3

While some surveys indicate that exurban tendencies may not be as strong among lower socio-economic groups and inner-city racial and ethnic groups, these groups generally appear to share the housing and locational preferences of the American population at large. A small, but intensive survey of Black youth in Boston indicated that the overwhelming majority of the children surveyed preferred home characteristics of the country or suburbs when asked where they would like to live their adult lives. Fifty-four of the sixty participants wanted suburban housing: “a one-family house . . . with a big fence around it. . . a garden and a place where kids can play;” “a one-family house out in the suburbs with a big back yard and not too many neighbors around;” “A pretty fair size white house.”[4]

Lastly, results of a survey conducted on youth preferences in Sweden demonstrate that the desire to live outside cities is not restricted to Americans. Although Sweden is frequently cited by planners as a nation of well-planned cities and suburbs, its youth are apparently unimpressed. The Swedish Institute for Public Opinion Research reported that 83 percent of its respondents indicated the desire to live outside of cities. Half of this number preferred small towns; the other half would opt for the countryside. Only 14 percent expressed a desire to live in a large city.[6]

There are, of course, some good reasons to be cautious about generalizing to isolate on preference variables, such as living location, without dealing with the question of trade-offs. If respondents are left unaltered by an exurban living location—accessibility to employment opportunities being the most obvious—the degree of strength of such preference cannot be adduced. Certainly the fact that many people do not appear to act upon these expressed preferences would appear to indicate that such trade-offs are potentially significant in explaining the differences between necessities and wants.

Still the residue of a paradox remains: one of continued urbanization—although at technologically permitted low densities—and the persistence of varieties of ambivalent and negative feelings toward cities and urban life.

Anti-urbanism in Children’s Literature

In these days when even preliterate children seem to be able to operate iPads, iPhones and iPods, the image of the parent sitting on a child’s bed reading bedtime stories into sleepy little heads might seem anachronistic. But there was a time when many parents, as I did, read stories to their children, some of these stories, as we shall see, that unwittingly might have instilled in their young minds the notion that there was something negative and even sinister about the city.

What follows is a selection of children’s stories that are written for that impressionable age range. While it can be argued that they are not intentionally anti-urban, their dramatic themes of contrast and conflict tend to elevate the pastoral over the urban, nature over the man-made, and the organic over the mechanical. In these contrasts nature is often portrayed in fanciful terms that are appealing to children, but the insidious effect might be to prepare their minds with for anti-urban themes that are taken up when they are exposed to the Bible, Dickens and other literature.

So this is a very selective set of examples, and is in no way meant to suggest that it is representative of all children’s literature, just that part that seems to employ a strong anti-urban bias.

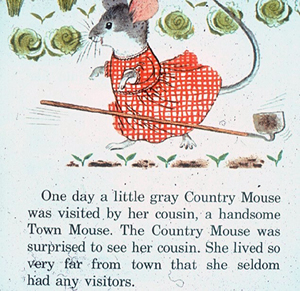

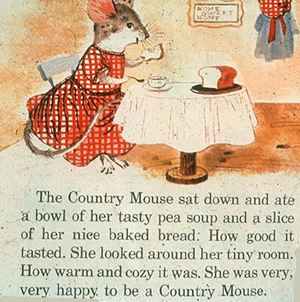

City Mouse/Country Mouse [6]

Perhaps one of the classic pieces of children’s literature is the one from which I have chosen the title of this paper: Aesop’s fable, the story of “The City Mouse And The Country Mouse” (the city mouse is, in some versions of the story, referred to as the “town” mouse, and there have been many embellishments upon the original over the ages). As children many of us have probably this story had this story read to us, but for those who have forgotten it, or somehow missed it, I will briefly recap its simple theme.

City mouse pays a visit his country cousin (in some versions of the story both mice are female). The latter lives rather simply in a comfortable and spare mouse hole. She dons a clean apron and puts out her best food and crockery to serve her cousin a lunch. “Here cousin,” she says, “have a nibble of our nice good crusty country bread.” But her city relative replies that where he lives he has butter on his bread.

City mouse then proceeds to remark on how dark abode seems to be in comparison with the large, bright sunny rooms where he lives in the city. Immediately, country mouse begins to fear how much better conditions are in the city—better food, better accommodations, even dressing on the salad. In general things are described as not being as luxurious in the country as they are in town.

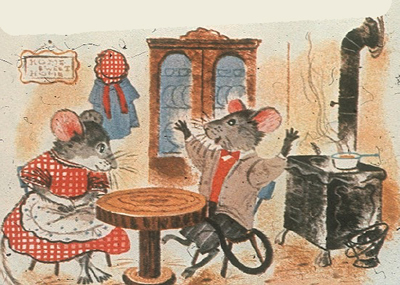

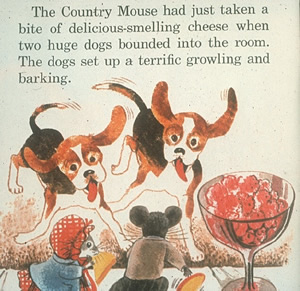

So, country mouse decides to return to the city with her cousin and check out this urban opulence firsthand. As predicted the food and the accommodations are far superior; however, there are indications that there is a price attached to this luxury. First of all there humans around, and we’re well aware of their antipathy to mice. And where there are humans there are often dogs and cats, the latter the archetypical enemy of mice. It doesn’t take country mouse long to conclude that it is safer in the country, were apparently better exist no hawks, snakes and a variety of other wild creatures that feed upon mice.

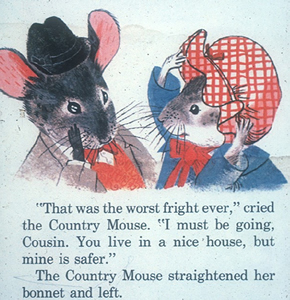

The story closes with the country mouse home again, now more appreciative of the values of country life and quite relieved to be back.

As suggested earlier there are a number of versions of this little story. It is perhaps interesting that in one version there were two additional dangers that threatened the little mice, a vacuum cleaner and an automobile, more than hinting at the curses of technology in the urban environment. Salient themes of the story are the suggestions of competitiveness in the city, the suggestion that the abundance of food leads to more in the linked way of life, and thirdly, the contrast of the unnatural miss of urban life with the implied natural and harmonious rural setting.

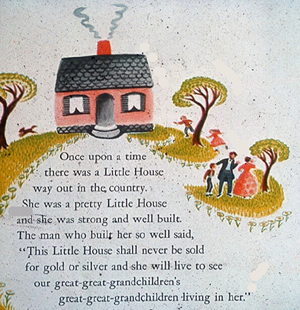

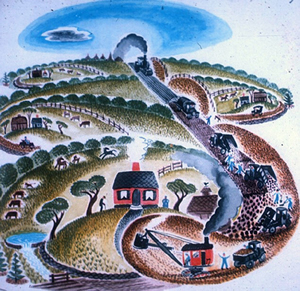

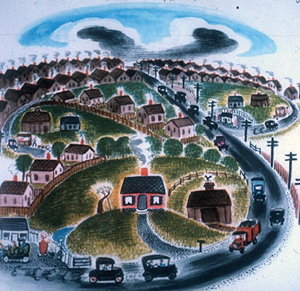

The Little House [7]

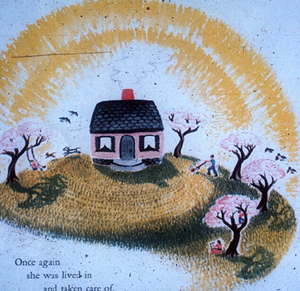

This popular story of the history of a little country house, by Virginia Lee Burton has been around since 1942, has won awards and was made into an animated cartoon short film. The story depicts an anthropomorphized little Cape Cod house enjoying the passage of the seasons in a pleasant country setting. Strong associations with family, and the spacious natural environs create an idyllic tableau. Another picture shows clear skies, grazing farm animals and fields of flowers. A night view shows the lights of the city in the far distance. Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter views show the changing of colors in the surrounding farmlands confirm that the seasons govern that world of the little house.

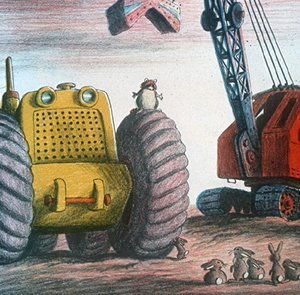

But soon there are indications of what is to come—first bulldozers and then subdivisions begin to appear from over the horizon.

But soon there are indications of what is to come—first bulldozers and then subdivisions begin to appear from over the horizon.

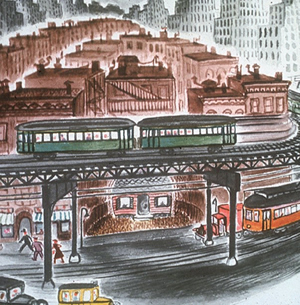

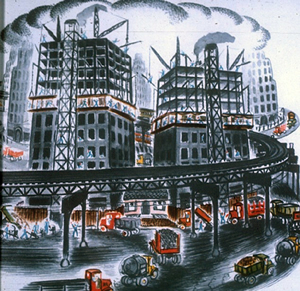

Notice how the sky and atmosphere becomes more tenebrous with the urbanization. Density increases inexorably from single-family houses two temperaments, and houses grow browner and blacker, the environment bleaker, and eventually elevated rail lines and streetcars appear as do wedding cake skyscrapers and the subway. All the while, bravely, the little house clings what remains of its original site.

We can barely make out the little house now and the text recites several anti-urban themes: people rushing around rather aimlessly, crowds and dirt, the spatial competition between people and technology, the general lack of permanence. The little house is now able to see the sun only at noon when it was not blocked by the surrounding buildings and the city lights obscured the moon and stars at night. She is shabby and her windows are cracked. ‘The only solution is for the little house ultimately to leave the city and return to the countryside, where like the little mouse, it is again happy. The story offers a little more frightening view of the city. In this case, unlike that of the little country mouse, no choice was offered to the little house.

Farewell to Shady Glade [7]

This contrast with the unpleasantness of the city and the return to nature and the restoration of happiness is a recurrent theme. Farewell To Shady Glade is a book dedicated to Rachel Carson and the glade, not too distant from a city, is a

peaceful setting of sycamores, willows and cottonwoods populated with a variety of Disney like little forest creatures—rabbits, a skunk, possums, racoons, a frog and some birds—who get on together without ever a thought about how their friendship is disruptive of the food chain.

peaceful setting of sycamores, willows and cottonwoods populated with a variety of Disney like little forest creatures—rabbits, a skunk, possums, racoons, a frog and some birds—who get on together without ever a thought about how their friendship is disruptive of the food chain.

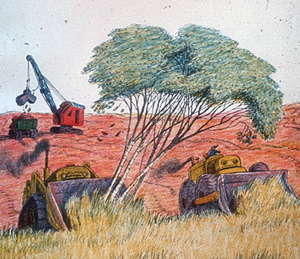

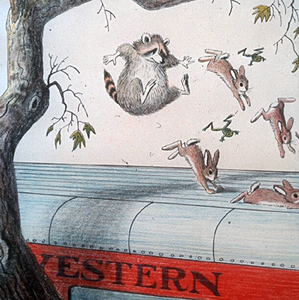

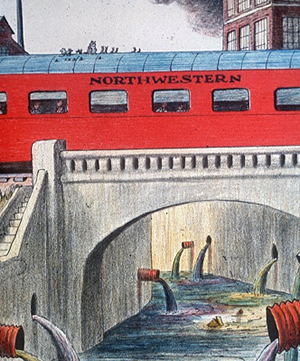

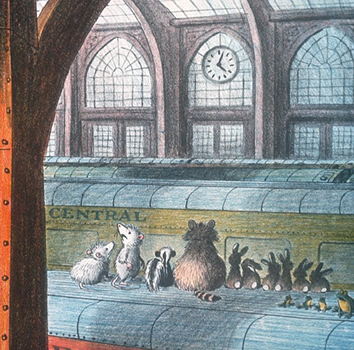

Once again, the villainous bulldozers intrude into nature, in this case a pleasant sylvan glade. The little creatures of the glad must make a plan for their survival as gain it becomes necessary to take flight from the uncompromising technology of urban development.

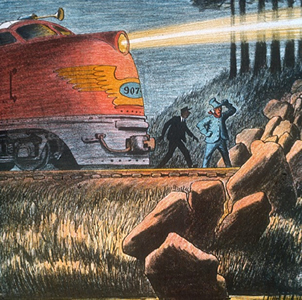

They make a plan of escape, even the dragon flies are in on it. In this instance with a little bit of help from technology in the form of a train the animals take flight and, n the course of their trip, are given a glimpse of what will eventually come to pass in Shady Glade as their train passes through the dark, polluted and deteriorated city and its netherworld like train station.

The familiar resolution of the problem—out into the country, back to nature and to happiness. Nature lends a hand by stopping the train with a rock fall and the little forest critters, now presumably at some safe distance from the invasive metropolitan monster, disembark into the natural environment.

The familiar resolution of the problem—out into the country, back to nature and to happiness. Nature lends a hand by stopping the train with a rock fall and the little forest critters, now presumably at some safe distance from the invasive metropolitan monster, disembark into the natural environment.

The City in Summer [8]

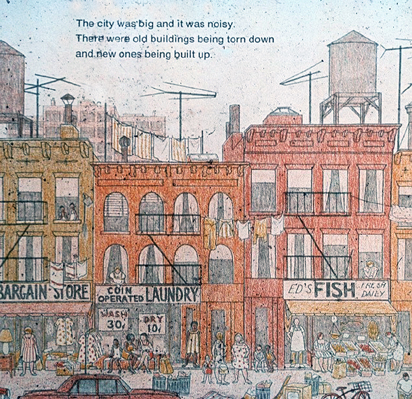

There are a lesser number of children’s books that portray city life in such stark terms. Perhaps because urbanism is more complex and hence difficult to communicate in terms easily appreciated by children The City In Summer contrasts with the previous books in its rather ambiguous message about city life. The City In Summer, with its bright, pastel illustrations of city scenes, depicts city life in a more neutral key. The establishing frames show a medium density urban environment of tenements and mixed land uses.

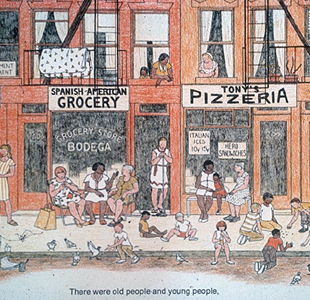

It is emphasized that the city is a place of both density and diversity.

It is emphasized that the city is a place of both density and diversity.

Another frame shows that the same crowded street, but states that it gets hot in the Summer and there are no places for the children to play, except the roof tops of the tenements.

Another frame shows that the same crowded street, but states that it gets hot in the Summer and there are no places for the children to play, except the roof tops of the tenements.

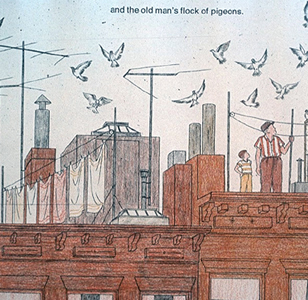

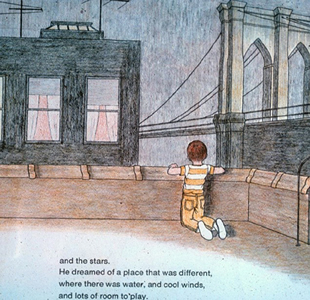

Without any specific introduction, the story now turns to a little boy who is befriended by and elderly neighbor man who keeps pigeons on the tenement roof. But from the roof we are once again reintroduced to the theme that the city appears to place a wall between man and nature (with the notable exception of those urban birds, the pigeons).

Without any specific introduction, the story now turns to a little boy who is befriended by and elderly neighbor man who keeps pigeons on the tenement roof. But from the roof we are once again reintroduced to the theme that the city appears to place a wall between man and nature (with the notable exception of those urban birds, the pigeons).

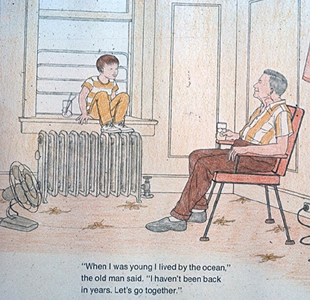

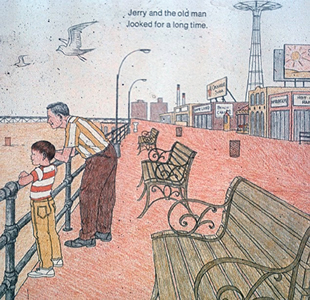

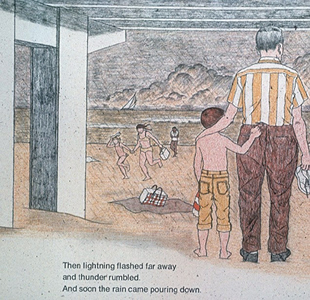

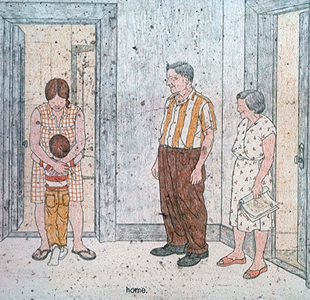

In a spare, hot tenement room the elderly neighbor suggests a trip to the seashore. While such neighborliness might be considered a positive element (especially when there are probably more negative associations with such encounters these days), one might be given to wonder why the little boy seems to have no recreational relationships with his peer group. The elderly neighbor and the boy take the subway to the seashore.

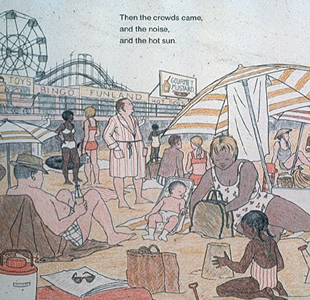

The seashore provides a place for quiet contemplation, but again reflects the representative restorative powers of the nature theme. However in this case it is somewhat spoiled by the emerging Coney Island like crowds, although nature intervenes a little here to disperse them from the beach with a rain squall. The story ends on a more ambivalent note than the others we have reviewed. The boy is safely returned to his mother, but the has been portrayed as a hot, dense place with little room to play. Summer in the City is closer to reality. It is the only story that involves humans, and particularly a young boy as its prime focus. Moreover, its anti-urbanism is not the romantic dis-urbanism of the other examples, but is tempered by a recognition that the city is a place of diversity and change.

These four examples do not, of course, give a complete picture of anti-urban and pastoral romantic themes in children’s literature nor, do I intend to suggest that these themes dominate such literature. Moreover, I have chosen examples largely from those written for a narrow age bracket; although in this case my purpose was to choose those aimed at the earliest impressionable ages. No claim is made here that there was a comprehensive survey of children’s literature, which is not only vast and diverse, but also the subject of some academic specialties. Much of that literature deals with fantasy and fable and what I did survey convinced me that the them of the city is rather complex both visually and conceptually, and so is less a subject for children’s literature. There are also some themes where the country has been portrayed negatively, Little Red Riding Hood, for example.

The obvious question that arises from what is been presented thus far is: what are the effects of this literature upon children and their subsequent attitudes about cities and city life. Such effects would be quite difficult to isolate; there are a variety of other sources from which children can receive exposure to anti-urban sentiments. The theme is further reinforced throughout literature, and the lament over the fate of Shady Glade may simply prepare children for more sophisticated negative urban views when they graduate to Thoreau or the Bible. It therefore seems reasonable to hypothesize that children’s literature represents in a simplified and distillate form far more complex and multidimensional causes for the formation and persistence of anti-urbanism.

___________________________________

©1973, ©2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.3.2014)