The news had just come over the radio as I lay in my undersized bed in my undersized flat in Hong Kong: Deng Xiaoping, China’s “great leader,” was dead. He was 93, not bad for a diminutive guy who had survived the civil war, the Cultural Revolution, and several million cigarettes, to usher his country into the world of market capitalism and unprecedented economic growth and change under the slogan “to get rich is glorious.”

The news had just come over the radio as I lay in my undersized bed in my undersized flat in Hong Kong: Deng Xiaoping, China’s “great leader,” was dead. He was 93, not bad for a diminutive guy who had survived the civil war, the Cultural Revolution, and several million cigarettes, to usher his country into the world of market capitalism and unprecedented economic growth and change under the slogan “to get rich is glorious.”

Then the phone rang. It was my brother, calling from San Diego. Our father was in the hospital. The prognosis was not good: my father might only outlive Deng by six months to a year. I would miss witnessing the handover of Hong Kong to China in July and be back to have a couple of months with my father before he was gone.

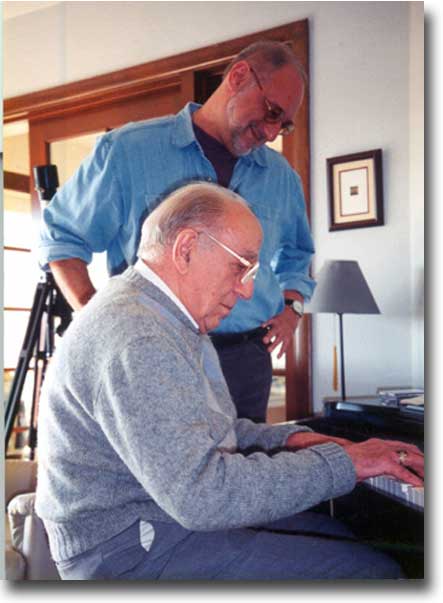

A half dozen “fathers’ days” have passed since then, but I think of him much more often than that, and every time I sit down at the piano. I miss our little jam sessions.

And everytime I hear Deng Xiaoping’s name I can’t help but think of my father. The contrast. Deng’s death would be noticed by literally billions of people. There would be so few who would remember my father, but I knew with certainty that everyone who knew him would remember him with love and respect. Deng led a huge nation; my father, just a family. But Deng was the “father” of the new China; my father was an exemplar of selfless fatherhood.

Fatherhood has gone though a lot in recent decades. The so-called “women’s movement “ has battered it’s familial hegemony, the traditional pater familias role has been compromised by the necessities of two-income families, paternal blood ties have been attenuated by the fact that four out ten kids today have a step-parent, and there has been the sense that fathers have been left behind in the various movements scrapping for political niche recognition.

Political conservatives and fundamentalist preachers rage and rail at the problems besetting fathers today, often assigning blame on easy targets like feminists, gays and opponents of school prayer; but the roots are deeper and more systemic in the social soil. There are perhaps no more pathetic and whiney illustrations of fatherhood’s contemporary identity crisis than the emergence of sappy organizations such as “Promise Keepers,” and events such as the “Million Man March” on Washington, or inanities that “men are from Mars.”

Like most every father in history I became one without much of a clue of its importance and complexities, and struggled to get through my part of parenting without negating the blessings of their mother. I have Dad to thank for how well I did. I’m grateful that, unlike Deng, he didin’t have whole nation to lead. When it comes to fatherhood, Dad was my “great leader.”

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 6.20.2004)