[This concludes the Cinema China series]

© 1974, Paramount Pictures

Chinatown, USA

Chinese often viewed America as the jin shan, “Gold Mountain,” the name given by the Chinese to western regions of North America, particularly California, but also British Columbia, after gold was first discovered in the state of California in 1848. Thousands of Chinese from southeastern China began to migrate in search American riches. Chinese immigration preceded the Gold Rush, but the yellow metal held out promise for more rapid riches than the cold steel of rails and railroad spikes of their previous experience earlier in the 19th Century during which they worked as laborers, particularly on the transcontinental railroad, such as the Central Pacific Railroad. They also worked as laborers in the mining industry, and suffered racial discrimination. While industrial employers were eager to get this new and cheap labor, the ordinary white public was stirred to anger by the presence of this “yellow peril.”

This was the flipside, the Asian-American side, of the East-West cultural interchange, and much of the cinematic attention to this phenomenon that has attracted my (descendant of immigrants) interest is that concerned with acculturation and cultural fusion. Several films, by and about Asian-Americans, focus upon this dynamic. Hong Kong-born Wayne Wang’s Chan is Missing (1982) is illustrative of the interplay of cultures. Although a simple mystery about the search for the missing Chan, it is also an oblique reference to the American-made Charlie Chan series of films that never was, and still is not, in any way insightful about the Asian-American experience. The quest for Chan becomes incidental to an immersion into the culture and everyday life of San Francisco’s Chinatown. The excursion, guided by two taxi drivers who are trying to find the missing Chan and the $4000 he has of theirs, is really a journey though a part of immigrant America that had not been so exposed cinematically by one of its own. The audience is taken into restaurant kitchens, offices, bars, flophouses, not finding Chan, who is replaced by an emerging portrait of the complexity and richness of this blended culture.

Wang followed his examination of Chinese-American life in San Francisco with Dim Sum (1984), a lightly plotted comedy of the Tam family that illustrated how traditional Chinese values and emotional complexities have been retained and influence intergenerational relationships. However, the extent to which the old world past invades and influences the new world present is well told in Wang’s Joy Luck Club (1993) about a group of Chinese-born women who meet regularly to play mah-jongg in San Francisco. Though they now lead comfortable lives, their pasts in prerevolutionary China, a time of famine, forced migrations, and privations that often required great personal sacrifices, are indelible and intrusive. Though their daughters are Americanized and successful, their filial relationships are greatly influenced by their mothers’ pasts. These pasts include that of one mother who was one of her husband’s multiple wives, another who had children taken from her, and another who was forced to abandon her children.Joy Luck Club demonstrates convincingly that, as the new American immigrant filmmakers take their place alongside their predecessors, American cinema is vastly enriched by these cultures, their pasts, and their adjustments to American urban society.*

Adjustment does not come easily for the hero in Pushing Hands (1994), by Taiwan-born, US-educated, writer-director, Ang Lee. Mr. Chu (Sihung Lung), a tai chi master, copes with his new life in well-to-do suburban Westchester, NY by maintaining the rituals of his former Beijing life: exercising with his tai chi quan, listening to Peking Opera, watching Chinese videos, and preparing his own Chinese meals. Chu’s son, Alex (Bo. Z. Wang), is, in some sense, the new immigrant success story, a well-paid professional, married to an Western woman, Martha (Deb Snyder), who is a writer. They have a young son to carry on the family name. The problem is that Mr. Chu is just a little too exotic for Martha, who is home with him the entire day and cannot abide his cooking and Chinese music.

Pushing Hands brings together multiple dimensions of the immigrant experience: intergenerational differences, the difficulties of those who immigrate when they are older, and the differences between the ethnic enclaves of Chinatowns (which function as retreats and halfway houses for immigrants), and the cultural blandness of suburban existence. While it is a comedy, there is a core truth to the predicament of Mr. Chu, who is not only foreign, but in many ways superfluous. In the end, Chu manages a bittersweet compromise with America, immersing himself in the society of urban Chinatown and drawing upon his tai chi to restore some connection and balance in his life.

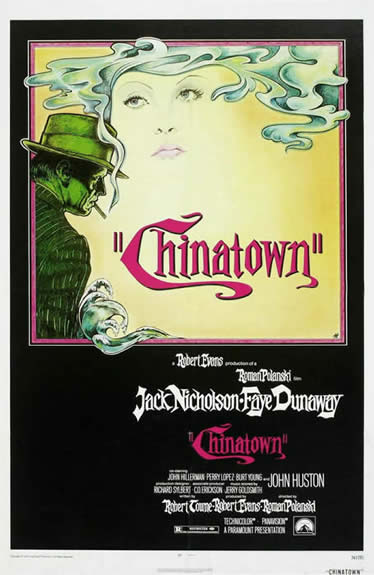

Chinatown finally becomes metaphor in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), in which LA’s Chinese enclave exists as a mysterious, exotic alternate urban universe with its own rules and rationality, “explicable” only by the invocation of its name. As a “location” of only scant appearance in the film it nevertheless exhibits its power in the influence it plays upon character and plot. In the concluding scene private detective Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) is rendered powerless in the re-enactment of an attempted (only alluded to) good deed years earlier in Chinatown that results in the death of another woman with whom he had become involved. When it all goes horribly bad Gittes is told by police detectives to: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” In other words, it doesn’t fit our notion of what’s rational, or explicable. The Chinese might say, “shi zhei yangde.” That’s just how things are . . . in Chinatown.

Cinema again played mediator for me, in Hong Kong this time, about a decade later. It was there that I boarded a venerable, old, green and cream Star ferry at Tsim Sha Tsui on a bright Spring afternoon.

As it rocked gently at its mooring I shuffled along with a crowd of passengers down the gangway, boarded and took a seat on one of the reverse-directional benches. It was nothing I had not done many times before, but on this occasion (my return to Hong Kong on sabbatical to study what was being called “the handover” on July 1, 1997) there was a significant difference. This time a few rows ahead of me the back of a girl wearing a khaki trench coat caught my notice. Her raven black ponytail brushing against its collar evoked a reverie of the opening scene of The World of Suzie Wong, a movie I had first seen in New York nearly forty years before, but which had given me my first impression of Hong Kong. In that scene actor William Holden walked the very same gangway and took a seat across from a fetching Chinese girl, played by Nancy Kwan, wearing a khaki trench coat, her hair in a ponytail. I could see her again in my mind, the beautiful face with the quick, flashing expressive eyes. But as the scene replayed from my memory as vividly as that day I first saw it, it now seemed I was in the scene itself. Somehow I needed to see the face of that girl seated up ahead with her back to me. Would she look like Nancy Kwan? Would she be Suzie Wong incarnate?

But when the passengers began disembarking my view of her was blocked by a large western man as the girl walked on the other side of him, allowing only tantalizing glimpses of her ponytail. I rushed to the other side of the funnel housing in the middle of the ferry, but was blocked by other exiting passengers. All I could see of the girl was the back of her as she alighted the gangway. I struggled to catch up with her, but once outside the terminal at Central she vanished. I suppose that, were he present, Jack Nicholson would have explained my perplexity with the resignation: “It’s Chinatown.”

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.22.2014)