© 1937, MGM

The good earth of MGM’s expensive ($2.8 million) 1937 film of Pearl S. Buck’s award winning book was not of Chinese soil. Filmed entirely on a five-hundred-acre farm in Chatsworth, California, the movie probably said as much, if not more, about America as it did about China. Given that the preponderant portion of Chinese society was composed of rural and village life,The Good Earth was an apt introduction to American audiences of a people and a place known to them at the time primarily through the mentality of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1924, Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu films, and encounters in local “Chinatowns.” In short, the Chinese were perceived primarily though that good ole American bugaboo—racism.

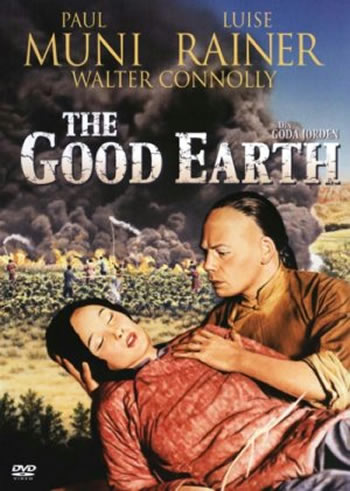

Under Sidney Franklin’s direction the story is about a peasant couple in rural China. A simple, poor Chinese rice farmer, Wang Lung (Paul Muni), weds O-Lan (Louise Rainer) a slave from a manor in an arranged marriage. They endure hard labor, poverty, and a severe drought and famine, while she also bears children. It is also a time of a revolution and their lives are transformed, Wang becoming the wealthiest landowner in the province. But his all-consuming greed begins to bring about the disintegration of his family, involving his desire to take another wife. Eventually a swarm of locusts brings him down. In the end, he learns too late that his long-neglected, self-sacrificing wife was the essential element of his good fortune.

MGM intended to make the film in China, but the Chinese government was divided on giving permission. The officials resented the novel, charging that it focused on the country’s backwardness; but some government officials felt they might better be able to control the film than if it was produced outside China. Permission was granted, with the intervention of Chiang Kai-shek and likely, Mme. Chiang, on condition that the view of China be favorable, that Chinese government would supervise and have script approval, and that the entire cast be Chinese. This last matter itself was a deal breaker. Despite the fact that Pearl Buck, as well as producer Irving Thalberg, wanted the film to be cast with all Chinese or Chinese-American actors, not only were American audiences were not ready for such a film, the Hays Code anti-miscegenation restrictions required Paul Muni’s character’s wife to be played by a white actress. This ruled out American-born Chinese actress Anna May Wong, widely considered to be the ideal fit for the role of O-Lan that went to German-Jewish actress Louise Rainer.* Many of the characters were played by Western actors in “yellowface,” with a few supporting cast including Chinese Americans.

The requirement for an all-Chinese cast was not enforced an the government in Nanjing did not foresee the sympathy the film would create, but when shooting began n location in China authorities became officious and tried to micromanage the project. The production was moved to California, most of the China footage disappeared and most everything had to be re-shot in Chatsworth.

Despite these difficulties The Good Earth was included in a distinguished list of nominees for “Best Picture” in the 1937 Academy Awards, losing out to The Life of Emile Zola (which also starred Paul Muni), but garnering a “Best Actress” Oscar for Luise Rainer. The movie also won “Best Cinematography” without benefit of the real China as a location (although the impressive special effects of the locust plague scene might have been very influential). But, importantly, Asia was beginning to receive serious subjects and realistic stories.

In the same list of distinguished nominated films was Lost Horizon,** Frank Capra’s rendering of the James Hilton romantic fantasy adventure of a group of British refugees led by diplomat Robert Conway (Ronald Coleman)

fleeing a Chinese city in the chaos and violence of the civil war and Japanese invasion. Coincidentally, it was shot just a few miles away from The Good Earth, not in China or Tibet(?) where the story takes place.

After their DC-2 passenger plane barely escapes desperate crowds and marauding soldiers it is hi-jacked and they fly through the night toward an unknown destination. The pilot makes no announcements over the public address system and the flight attendants just as informative. In the morning they look out the plane window and see huge, snow covered mountains from horizon to horizon.

The small group of passengers that includes Conway’s brother, a swindler and a consumptive prostitute wonder where they are when they discern that they are flying in the wrong direction, but wonder is soon replaced with worry as the plane begins a rapid descent. A terrifying few minutes ends with the plane half-buried in the snows of a high mountain valley. Everyone is alive and unharmed, but there’s a lot of praying, cursing of airlines, and anxiety about uncertain fates, until through the blowing snow some lights can be seen approaching the plane.

Soon appear people with beatific, smiling, ambiguously-Asiatic faces (the sort of faces you get when Western actors are made-up to play Tibetan monks). They dress the survivors up in warm animal skins and lead everyone through a pass in the mountains. Suddenly they emerge above a sunlit valley with streams, woods and fertile farms and orchards, and a pleasant, clean, cute and orderly town. They are in Shangri-La, where people hardly age at all and live apparent lives sybaritic indolence for hundreds of years.

That is what Conway is told by the, Chang (H.B. Warner) head monk in “yellowface” that looks like a cross between John Guilgud and Bruce Lee. They are welcome to remain in this remote mountain retreat from the global economic depression and impending wars of the late 1930s, but should they subsequently leave Shangri-La their suspended years of aging will be instantly come due.

In the end some stay, some leave, among them Conway, who has fallen in love with local girl Sondra (Jane Wyatt, who conveniently, and perhaps in respect of the movie code, is distinctly un-Asiatic in appearance), to try to save his brother, but is trying to find his way back to Shangri-La when the movie concludes.

But Westerners were not always ready to cut and run to Shangri-La when things turned unsettled and dangerous in China. A colonial cohort of British, Americans, French, Italians, Russians and Japanese held out for 55 Days in Peking, the 1963 Nicholas Ray re-creation, in Madrid, Spain of the siege of the British Legation compound by the Boxers sixty-three years earlier. Charlton Heston, Ava Gardener and David Niven played Westerners, but yet again the roles of the Dowager Empress (Flora Robson) and Gen. JungLu (Leo Genn) went to Westerners as well, perhaps explaining why they colluded with the Boxers, who vastly outnumbered the Westerners. Or, it could have been what a never-made sequel would have shown after the delegation was rescued by a “cavalry” of superior force that opened up a despicable period of rape, looting and killing (not that the Boxers had covered themselves in humanistic glory). Had the movie employed a more wide-angle lens than just fifty-five days it might have been a cautionary tale for hubris of foreign powers who would impose themselves and their ways upon other peoples.

Especially when those people are embarking on a long and fractious internecine spat.

[To be continued]

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.10.2014)