© 2014, UrbisMedia

Since I have been unsuccessful in finding any ancient Romans to chat with I have long felt the urge to put to use those four years of Latin I slogged through in high school. I always liked Latin for its ancient color when we translated a lot of Caesar’s Gallic Wars, less so its mumbo-jumbo function in the “holy sacrifice of the mass” (taken away by the modern vernacular reforms to expose the prosaic supplications beneath). But that wasn’t quite why I stopped attending. Dies iræ! Dies illa/ Solvet sæclum, in favilla.

I think a little Latin adds richness and distinction to one’s modus scribendi, since English already gets a good deal of its origin to this mother of many European languages. I conjured the neologism (from the Latin) blogoscenti, for the quid nuncs (news hounds) who get most of their information and opinions from blogs. I think we need a word like this. If blog comes from “web-log” it already begins with the Latin logos, for “word.” Actually, I hate the word “blog.” (Please don’t call DCJ a blog, although it isn’t literally a “journal” either. It’s really sort of what the French used to call pensée, I guess, but forget that, too, unless you are having some paté and a bon vin rouge while reading this. Christ! Help me shut down this obiter dictum!)

There are distinctions in Latin that make a lot of sense to me. Cognoscenti, a term that has made slight inroads into the English lexicon, means “those who know (about),” somewhat in the way someone is “informed.” But it doesn’t mean knowledgeable in the way the term sapientimeans “wise or “intelligent.” Cognoscenti might be “in the know” about some things they share with others, but they might not be sapienti. The same distinction turns up in the French verbs “to know” (which they have the conquest of Gaul by the Romans back in the 60s B.C, to be grateful for).

My Latin lexicon might be no more than my private way of marking or trying to find an apt term for a new phenomenon. For example, I recently came up with a term for the new (or revived) phenomenon of tattoo-ing. No longer restricted to drunken sailors, but popularized by the likes of Angelina Jolie, rock stars, and sports heroes, the tattoo is the “in thing” (or “on” thing) for many dermatologically narcissistic people I like to call illustrati, “illustrated people.” One can even use a gender distinction for an illustrated women (illustrata, or illustratus, for a man), since new to this revived interest in self-decoration is the number of women who engage in it. Tattoos can range from a simple flower or Chinese character on a shoulder, to a ubiquitous “graffiti” that looks like it was done in a prison by a blind inmate with palsy and a repertoire of death heads and Nazi symbols. Seeing a lovely young woman with inked daggers, Harley Davidson imagery, or arms completely obliterated with flames or floral patterns (vidi) changes my mumbled utterances from dea certe, to lacrimae Christi!, as though a statue of a goddess had been desecrated by a gang tagger from East LA.

Then I discovered that I needed a word for the other fashion of sticking ugly chunks of metal through one’s nose, tongue, lips, eyebrows, ears, etc. This act of “beautification,” or revenge against airport metal detectors, at least does not necessarily have the permanence of being among the illustrati, although the invitation to infection or death by high-powered magmnet might well obviate such concerns. In any case the puncturati (“the pierced ones”) defy my notions of corporeal (from the Latin corpus, for body) self-respect as much as do the dermal doodles of the illustrati. Together (and sometimes they occur together on the same person), these categories of personal disfugurement can be referred to as deformitati.

One suspects that few of the deformitati are also sapienti. Since many of these newly illustrated and pierced cohort are young there seems reason to hypothesize that their attraction to these expressions are foolishly faddish. Ours is a society consumed with both conformity and personal identity, especially among the young. Their clothing, music, language, hairstyles, films and television programs and, especially, personal presentation are crucial in establishing who they are (or what group they choose to belong to). They used to distinguish themselves with something as innocent as a T-shirt with their favorite rock group or that ubiquitous authority-challenging image of Che Guevera. When their allegiances, styles or tastes changed it was just a matter of changing their shirt. Who would want to be stuck with greasy DA hairdos, poodle skirts, bell bottoms, tie-dyes and puka beads today; if they were tattoos they would still be right there every time you take a shower saying “WTF was I thinking when I did this?” But not so with a becoming an illustratus with a bad likeness of Justin Beiber on your thigh, or a puncturatus with a lingering inflamed sinus from that nose bolt or urinary tract infection from that stud through you’re your-know-what.

But my biggest concern about this fad or fashion as adopted by the young is the negative prejudice it is likely to invite. It might be cool to have a flowery vine or crusader sword (gladius) rising up your spine from your butt crack when you work as a café barista, Harley mechanic or a pool boy. But it will be more difficult to pass employment muster at a day care center, or any number of jobs that involve customer or client relations when you have a lizard winding up on your neck, or swastikas on your knuckles. The reality is that unless you are a Maori or a Samoan, where traditional symbolic tattoos have tribal and associations and identifications, in our society your ink is likely to evoke associations with sailors, bikers and convicts. (I have no idea what’s up with African-American athletes whose illegible tattoos come off as some sort of vermiculated squiggles.) Are we likely to have in the future a minority of unemployable illustrati as a social and economic burden, with society having to foot the bill; for expensive laser removal of millions of inked skulls, psalms, crucifixes, Elvis likenesses, and hearts with the names of long gone lovers?

Admittedly, some of my critical reaction to illustrati and puncturati might well be assigned to generational distance. First impressions can be as indelible as a tattoo. Mine came when I was working a summer job in high school at an automobile dealer used car “doll-up” shop. I was assigned to assist the painter to get cars ready for a new paint job. “Bud” (not his real name, but he might be out of prison by now) was making a little extra on the side by, as I discovered, pimping his wife, “Belle” (her real name, but she’s probably dead by now). Bud had a huge black panther tattoo wrapped around his torso, made of enough ink to start a daily newspaper. He caught me by surprise shortly after I began working there when he said he wanted to show me “something [I] might like.” He escorted me behind the building where his “wife,” Belle parked in a convertible each day at the lunch hour. Saying “I want you to meet my wife” he pushed my head though the open window to be greeted by Belle fully exposed in “the wishbone position.” My head was close enough to discern tattooed on the inside of one ample thigh a leaping bunny with a scripted “Belle” next to it. On the other inner thigh was tattooed printing with an arrow pointing well to where it specified there would be an “entry fee.” It was enough to indelibly create a negative association with tattoos that has lasted to the present.

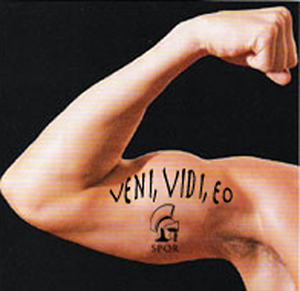

I can’t recall what I said to get myself out of that situation, but if I had gotten a tattoo to commemorate the occasion it would have been: Veni, vidi, eo! “I came, I saw, I’m outta here!”

___________________________________

© 2014, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.8.2014)