Period French postcard, with added fox by UrbisMedia

My mind kept returning to that last scene in Robert Towne’s screenplay of Chinatown (1974) when Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) is slumped over the wailing horn of her car, shot dead, and the cops who used to be Jakes Gittes’ (Jack Nicholson) colleagues restrain him, settling him eventually with the simple explanatory phrase that “It’s Chinatown.”

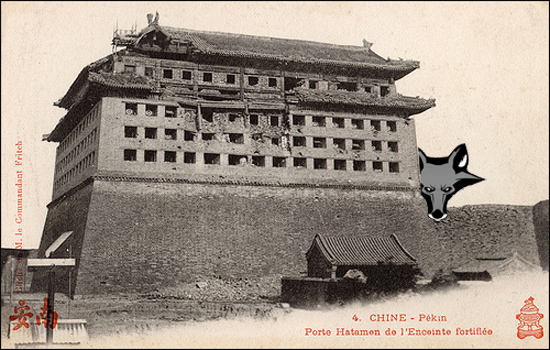

Beijing might be the ultimate Chinatown; not some neon-illuminated enclave of wok-steamed restaurants and the din of raucous dialects, but an imposing imperial scale of forbidden enceintes, legation quarters, intimidating squares and looming walls and towers, and interstitial dark and cramped hutongs. The grandly-scaled city can be imposing and spooky at night, especially for superstitious people who believe in ghosts and other spirits, like Chinese. That “Chinatown,” of haunting deep shadows cast by walls and towers might be especially daunting to the alien, to the denizen whose rationality might reject local myth and fable, but yet find a reason to exercise caution and restraint.

On the morning of 8 January 1937, the body of nineteen-year-old Pamela Werner was found at the foot of the Fox Tower in Beijing. All the blood had been drained from her body and in particularly gory detail, her heart was missing, ripped out through a gaping thoracic rift. In 1937 Peking was like a ship heading into a reef. China was in political turmoil with the KMT and communists vying for advantage while the opportunistic Japanese swallowed territory like an oozing bloodstain. By the end of the year, they would have taken Shanghai and be conducting rape and massacre in Nanking. Peking was full of spies, political turncoats, Russian mobsters, and Western ex-pats, with weak and shifting lineaments of allegiance. Out of this stew of intrigue and danger emerges a gruesome homicide. Something terrible happened in the night near the tower where sinister ”fox spirits” abide, that raises not only questions of the perpetrator(s) and motive but what was this attractive young woman doing out and about at midnight in Peking?

The story begins with Pamela’s father, China Hand Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner. He was the son of well-off English world travelers who took exams for a Far Eastern cadetship with the British Foreign Office and was posted to Peking for two years in the 1880s as a student interpreter. It was a period that the Chinese might have called “interesting times”; there had recently been the Taiping rebellion, (self-anointed Christ brother Hung Hsu-chuan’s attempt to overthrow the Qing Dynasty), or there had been the great drought and famine in northern China in the 1870s, and then, of course, the Opium Wars that concluded with the sacking and looting of Peking. When Warner arrived Europeans had already established legation quarters settled by diplomats, trade officials and missionaries. They were “yang guizi” (foreign devils) and called such in the streets of a city that was remote, bizarre, and dangerous outside of the European enclave. Walls, gates, and haunted places, segmented the teeming, sprawling imperial city into the “Tartar city,” Forbidden City, Chinese City, Legation Quarter, interspersed with temples and the tight, dense compounds called hutongs.

Werner loved it; he had found his place and he quickly moved his way up the diplomatic ladder with higher postings in the Peking legation, a year in Canton, a couple more internships in Macau, before a return to acquire a law degree in London. He was quickly back to China with postings at a variety of remote cities, including a four-year appointment as consul at Kiukiang. Now aged forty-five, and a full-fledged China Hand he decided to marry. She was Gladys Nina Raven Shaw, the daughter of a British military officer who had served in the empire’s conquered territories in the Asian subcontinent, and she was half his age. Gladys was accomplished at sports, music, well-educated, and attractive. She was apparently a good fit for Werner, settling into a rented four-story house near the Ch’ienmen Gate from which she liked to venture to explore her new environs.

Warner might have remained a lesser figure in the history of Peking at that time were it not, as it is often the case, that he was visited by tragedy. By 1937 things were much different. After several childless years, the Werners adopted a young Western girl from a Catholic orphanage. They knew nothing of the child’s parentage or even her birthdate; they named her Pamela. But Gladys would have only a short time being a mother, taking sick and dying in 1922 at age thirty-five. This left the grieving Werner to raise his five-year-old daughter as a widower. He never remarried and threw himself more deeply into his studies and writings about Chinese language, history, and culture. Pamela grew up independent-minded. Educated at a boarding school and Tientsien, she returned to Peking where she boldly plunged into its nightlife that was composed of cafés, clubs, brothels, and opium dens, people do with Russians, Europeans, and spies for the Japanese army preparing to invade the city.

The workers lived in number 1 Armor Factory Lane at the edge of the Legation Quarter nearby the massive Fox Tower close by the wall of the Tartar City. Since it was believed to be haunted by sinister “fox spirits,” it was an area that was usually deserted after dark. French writes that: “after dark the area became the preserve of thousands of bats, which lived in the eaves of the Fox Tower and flitted across the moonlight like giant shadows. The only other living presence was the wild dogs, whose howling The locals awake. On winter mornings the wind stung the exposed hands and eyes, carrying dust from the nearby Gobi desert. Few people ventured out early at this time of year, opting instead for the warmth of their beds.”

It was in a ditch below the Fox Tower that an old man from a nearby hutong who was taking his songbird out on a walk discovered the body of Pamela Warner. Her face and body had been so badly mangled that when her father saw it his most certain identification was on the basis of some of the clothing. It is almost a too-perfect set up for a murder mystery: an attractive and adventurous young girl of nineteen, who might already have had some amorous involvements with a schoolmaster in Tientsin, who was pursued by a well-off dentist in Beijing, and was frequenting nightclubs in areas of brothels, drug dealing, and espionage; a crime site of looming towers, dark shadows, bats and feral dogs, and the overriding superstition of evil spirits, and; ambiguous lines of policing authority shared by the Chinese and officials of the ex-pat communities in a city that is imminently threatened by the Japanese invasion.

The bulk of midnight in Peking attempts to deconstruct this grisly murder with the assistance of newspaper accounts, and official reports and documents. Two detectives, one British, one Chinese, attempt to work together under the pressure of their respective bureaucracies, suspects are investigated, lines of motivation are pursued, but without result. The trail grows cold and finally, in a belated effort of paternal responsibility, Warner himself immerses in the mystery, connecting many of the dots better than the detectives. But it is all too late. There is too much distraction of the turbulent history, people disappear and Warner who himself remains in China until 1951 finally repatriates to the UK that barely remembers him. Her daughter remained behind in her grave that now lies under the second ring road near the Fox Tower.

Edward Werner died in 1954 and is buried at Ramsgate. One suspects that he might have felt in the end, as we might, a little like Jake Gittes must have felt when confronted with the inscrutable he was told to just accept that “It’s Chinatown.”*

___________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 1.28.2014)

* French has also written about another China Hand: Carl Crow – A Tough Old China Hand: The Life, Times, and Adventures Of an American In Shanghai (2006). Beijing also serves as a setting for fictional murders and thrillers. See, for example, Carl Hiasson and William Montalbano, A Death in China (1998).