In my old Seminar in Planning Theory I used to give my students a series of small writing assignments. “In one I would task them as follows: A director of city planning is found dead at his desk, from a self-inflicted shot from his revolver. On the desk slightly splattered with blood is his suicide note. What does it say?” I received some interesting answers over the years.

In my old Seminar in Planning Theory I used to give my students a series of small writing assignments. “In one I would task them as follows: A director of city planning is found dead at his desk, from a self-inflicted shot from his revolver. On the desk slightly splattered with blood is his suicide note. What does it say?” I received some interesting answers over the years.

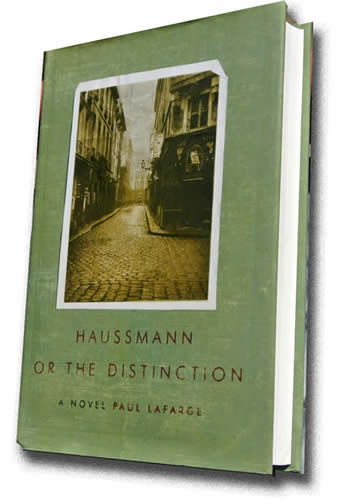

Paul Lafarge’s novel of Baron Eugene Haussmann, the Prefect de la Seine, the planner appointed Napoleon III with plenipotentiary powers to bring Paris into the emerging modern age, employs some literary leger de main. Lafarge leads the reader into that sepia gaslight era by posing his contemporary novel as a translation of a long forgotten novel of 1922 by a fictitious author who might have been born in the age of Haussmann. He even might have been in a position to verify the rather surprising alleged garbled deathbed confession of the Prefect that he regretfully “wished all his work undone.” One might imagine some contemporary urban planners renouncing some disastrous suburban monstrosities, or even the authors of La Defense in Paris needing to apologize; but the man most responsible for the physical Paris that the world has come to know and love should, it seems, have no cause for regret.

Not many novels would take a city planner as protagonist. Ask most people to name three renowned/influential city planners and you might not even get one. Who, outside of planners and urbanists themselves would name Fifth Century B.C. Hippodamus of Miletus, Pope Sixtus V, or most lately, Robert Moses of New York. As individuals they might well have been interesting persons with interesting personal lives, worthy of building a story around. But the city is a complex mechanism and, while it figures significantly as a “character” or influence upon plot in many novels, movies, and even paintings, it can be difficult to capture with the limitations of their frames.

It also may be that the reason we find scant material about cities and city planners per se and various works of art owes to the fact that, for the great part, most city planners do not really “plan” their cities. Few planners get to lay out an entire city ab initio, and even those that do, do not, other than the limited extent to which physical design is determinative of social behavior, influence the nonphysical, cultural dimension of the city that is its essence. Far more influential than the planners are scientists, inventors and technologists who, while not setting out with specific intent to influence urban morphology, often do so with significant “side effects” of their innovations.

When I gave a series of lectures to professors of city planning in America from various universities in Beijing I began by asking the rhetorical question of how many of them could name a famous city planner in America. I think one might have mentioned Philadelphia’s Edmund Bacon, who probably came to mind because of a book he had written on urban design, but otherwise the audience was silent. I then place the following list of names on the whiteboard: John Jacob Astor, Cyrus McCormack, Elisha Otis, Henry Ford, Bill Gates. They recognized Ford and Gates, but probably wondered just as much about them as the others as to why I called these men the most influential “planners” of the American city. Astor, who said that “landlords grow rich while they sleep,” was the first great real estate tycoon of the American city; McCormick’s inventions mechanized agriculture that increased productivity while sending erstwhile farmworkers to the city; Otis invented the elevator that made possible the intensive use of urban space; Ford’s automobiles probably had more to do with enabling the outward expansion of urban areas than anything else, and; Gates, who was representative of several progenitors of the information technology revolution, has brought about, and still is, optional reconfigurations of urban morphology. There were others of course, the Wright brothers, and Thomas Edison could also be included. None of these men however were concerned primarily or initially with urbanism or its form.

But the city planner, the urban administrator labors in a more reactive capacity, having to deal with the temporal exigencies and the forces of existing and changing technology as well as its capacity to be a tool in that process. There is of course more to city planning than simply reacting to the influences of technological innovation upon urban form since there is more than technological determinism that influences the character and quality, the culture of urban life.

Unless, of course, there are some aspects of Haussmann, some “distinctions,” that Lafarge provides that might make for such a last wish. After all, when Lafarge connects the Baron with a character named de Fonce who makes a fortune buying up properties that are demolished in the “half” of Paris that was in the path of redevelopment. And de Fonce is the adoptive father of Madeleine, who was given up to a convent-orphanage by a lamplighter father, only to escape, be plucked from the polluted Seine and end up the mistress of the Prefect and bearing his child (Haussmann was twice her age, married and had daughters her age). How real is Madeleine? She occupies nearly the first seventy pages in what might be a roman a clef with Haussmann in second position; but that changes abruptly and he is given thoughts and feelings. Haussmann sets up love nest for he and Madeleine in rue Le Regrattier on the Ile St. Louis, street referred to as “Headless Woman Street” (also “The Perfect Wife”) because there is an ancient headless statue of a woman on a corner building. Is this creative license? No, the street and the statue exist,* but we had to wonder since Haussmann erased much of old Paris. There were those, among them Victor Hugo, who hated him for it.

When Haussmann set to work Paris was a filthy, dark, feudal, foul-smelling city. He tore through it with expansive boulevards, gas lighting, over one hundred thousand new apartment buildings and over three hundred miles of new sewers, the latter an apt answer to the cholera epidemic five years before that had killed one out of every two Parisians. The dozen avenues radiating out from the Arc de Triomphe, the spendid open spaces of the new Bois de Boulogne with its two artificial lakes, the Bois de Vincennes and Parc Monceau, the innovative design of the glass and metal stalls of the food markets at Les Halles, to the contested transformation of the Île de la Cité and the parvis of Notre Dame, the innovative street tree planting schemes, all where the schemes of the tall Alsatian workaholic who was appointed in 1853 by Napoleon III soon after his accession to the throne. Not unrelated to the new open design was that troops and ordinance could be moved to trouble spots with greater ease and not be bottled up in narrow, barricaded lanes.**

Louis Napoleon had lived in exile in London and New York. He admired the parks and broad avenues introduced into the English capita in the Wren Plan after the great fire of 1666, and the efficient economic layout of Manhattan in 1811.*** And the economics behind such expensive grand plans was proto-Keynesian in concept: it would be paid for not by taxes hikes but by issuing huge government loans that would be retired by those who would most benefit from the rebuilt city, the public and the businesses that would prosper from this gigantic stimulus. Government spending would also fuel prosperity. And it would provide employment to whole armies of workers whose pay would add to the economic multiplier.

By 1870, Louis Napoleon was out, the French were defeated in the Franco-Prussian War and the Third Republic was about to be installed, and Paris was transformed into a modern city.

___________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 11.29.2013)