“My parents had a good reason for taking me to the movies all the time, because I had been sick with asthma since I was three years old and I apparently couldn’t do any sports, or that’s what they told me. But my mother and father did love the movies. They weren’t in the habit of reading—that didn’t really exist where I came from—and so we connected through the movies.

“My parents had a good reason for taking me to the movies all the time, because I had been sick with asthma since I was three years old and I apparently couldn’t do any sports, or that’s what they told me. But my mother and father did love the movies. They weren’t in the habit of reading—that didn’t really exist where I came from—and so we connected through the movies.

And I realize now that the warmth of that connection with my family and with the images on the screen gave me something very precious. We were experiencing something fundamental together. We were living through the emotional truths on the screen, often in coded form, which these films from the 1940s and 1950s sometimes expressed in small things: gestures, glances, reactions between the characters, light, shadow. These were things that we normally couldn’t discuss or wouldn’t discuss or even acknowledge in our lives.

And that’s actually part of the wonder. Whenever I hear people dismiss movies as “fantasy” and make a hard distinction between film and life, I think to myself that it’s just a way of avoiding the power of cinema. Of course it’s not life—it’s the invocation of life, it’s in an ongoing dialogue with life.” [Martin Scorsese, “The Persisting Vision: Reading the Language of Cinema,” The New York Review of Books, August 15, 2013, P. 25]

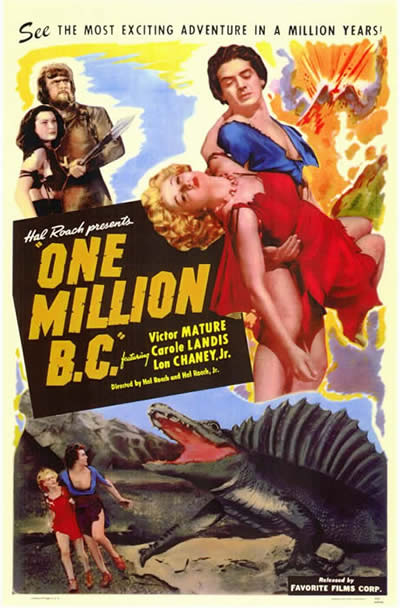

A few years ago, thanks to the wonders of the Internet I managed to find a copy of the very first book I ever read, a book long out-of-print but not out of my memory. Recently, thanks again to the Internet I was able to obtain a DVD of the very first movie I ever saw. I must have been around age six when my grandfather, Sebastian, who was my favorite playmate, took me to a small single aisle theater in a Rochester, NY neighborhood to see One Million B.C. (no, not the 1966 re-make with Raquel Welsh filling out a fur bikini; the 1934 original with Victor Mature and Carol Landis, directed by Hal Roach). Magically, the DVD arrived three days after I ordered it online. I was astounded how much I remembered of that movie. Nearly seven decades after sitting in that movie theater with my grandfather, now sitting in the comfort of my own living room, with my bowl of popcorn, watching on my high definition TV screen, I was amazed not so much at my mnemonic abilities as by the indelible power of the photographic image in re-creation of a narrative.

There was the young Victor Mature and the beautiful young Carole Landis just as I remembered them, he from the brutish and bellicose “Rock People,” she from the caring and communal “Shell People.” The simple story exploits that most fundamental element of drama, conflict, in the stark contrasts between these troglodyte social groups of supposedly 1 million years ago (plus the 70 since I first saw the film) and the ensuing tensions. It’s also the tried and true “boy meets girl,” but boy and girl are from different sides of the tracks, different faiths, different ethnic groups, different races, whatever, it’s the difference that makes the difference in dramas of the sort. We have seen it again and again from Rebel Without a Cause, to Peyton Place to A Patch of Blue, I could go on for pages.

But that is in retrospect. At the time, I was less interested in the boy meets girl part of the story than I was in the dangers that they had to overcome, not only from social differences, but from what was (also in retrospect) a rather curious menagerie that at the time I believed might well have existed one million years ago. There were mastodons, which now looked like exactly what they were, elephants dressed up in for, with loosely attached mastodon tusks. These coexisted alongside an array of dinosaurs, one a rather sad looking and diminutive to Tyrannosaurus Rex, but the others being played by real baby crocodiles with fin-sails attached, and a variety of lizards, all separately photographed in threatening postures and fighting with one another, rear-projected on large screens against which the players almost appeared to be in the same plane. For 1934, these were pretty good special effects and they certainly had a special effect upon me. I have read a good deal about evolution seen a good deal of the fruits of paleontology as well as the Jurassic Park series since then, but I would assume that the temporal and physical juxtaposition of humans and long extinct giant reptiles would find favor today with primitive minds of religious “creationists.”

Like the young Mr. Scorsese it appears that I was, on viewing my first film, not only consciously impressed by the narrative elements I was observing, but was also somewhat subliminally gaining an appreciation for the elements of production of motion pictures. Although we two East Coast Italian-American boys from the early 1940s took different routes—he becoming a renowned and respected film director and producer, and me approaching film (shameless plug alert) from an academic perspective*—we were both imprinted by those early experiences in movie theaters. In fact, I could not help wondering whether Scorsese had seen One Million Years BC as a young boy and also have been impressed by it. In the very same article quoted above Scorsese wrote: Light is the beginning of cinema … The desire to make images move, the need to capture movement, seem to be with us 30,000 years ago in the cave paintings at Chauvet—in one image a bison appears to have multiple sets of legs, and perhaps that was the artists way of creating the impression of movement. I think this need to re-create movement is a mystical urge. It’s an attempt to capture the mystery of who and what we are, and then to contemplate that mystery.

Curiously, twenty-four years earlier, on August 18, 1989 I wrote and aired an essay called “The Moviegoers,” on KPBS-FM. I wrote then:

The moviegoers file silently into the picture place. There is a sense of anticipation, even an undercurrent of anxiety in the knowledge that what they are about to see could move them emotionally. They are uneasy with the sense that what they are about to witness is magical, something with a curious power through which images come to life, quicken before their very eyes, like those images that come with sleep, in the mysterious worlds where the real and the imagined commingle.

They are seated now, hushed in the low light of the picture place, seeing each other only in silhouette and soft shadow. Then the magic-makers come forward with their magic torches; the wonder is about to begin.

Now the gleaming surface of the wall is illuminated, and creatures, familiar and strange, begin to dance in the flickering light, jumping here and there, on and off the walls and startled retinas. Horned beasts that the audience recognizes appear, their eyes mirroring the restrained fright in those of the moviegoers. In the next flickers, spears now seem to appear, entering the beasts, and there is blood on their necks and flanks. And now another creature appears—one that looks like themselves, but not: a man-beast, two-legged, but with horns and fur. In the flickering light, the man-beast dances and leaps about. To the side of the wall there appear more beasts, some big, some small, their legs jerking them over the surface, back and forth, tumbling them over one another.

The moviegoers gasp, or sit silent and wide-eyed. Some, who have seen the magic images before, are again fascinated. Others, seeing the images for the first time are enthralled, even terrified. But for all there is in the magic images the affirmation of a new truth that is part lie, a new stratum of reality, borne by the mysterious process as well as the images. They have been changed; they have no word to express it, but they have become the first moviegoers.

Movies are, existentially, about time. When we watch them we are in three parts of time simultaneously: the present (in which we are watching); the time of the place and technology in which the movie was made (watching the people photographed in the streets as they were in their time; and, in the re-creation of times past on film, transported through history. Cinema is time travel, maybe the only time travel that is possible, and I will watch almost any movie(some are pretty crappy) in which time travel is the narrative, just to get an aperçu, an idea of how time travel just might be possible.

Is it any wonder then, that sitting in my own living room viewing again my first movie, first seem almost seventy years before, I felt for a few brief moments transported back to that dark movie theater, sitting beside my grandfather Sebastian, smelling the aroma of his Di Noboli cigars clinging to his clothes, mingled with that of buttery popcorn, and watching in the flickerfing light the rock people and the shell people of one million years ago, I felt a little bit like a time traveler.

________________________________________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 9.30.2013)

*James A. Clapp, THE AMERICAN CITY IN THE CINEMA (NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2013)