The Cinema: a little script

INT: SUBWAY STATION, IRT, NEW YORK, MARCH 23, 2014

MEDIUM SHOT: Subway platform and train and modest crowd

ACTION. Mark enters the door of the IRT and about to take his seat when we see him reach into his coat pocket and extract is iPhone that is still playing its heavy metal ring tone. He smiles; it’s Molly.

CLOSE-UP: Mark’s iPhone. Molly’s face appears in the screen, live. There is street action behind her. It’s a bit shaky a nervous hand-held.

MOLLY (Stressed)

Baby, where are you? You are not going to believe this! Jennifer and I were just coming out of the

movie theater when we heard––and felt!––this explosion just down the street from us. Jesus, Mark,

it was incredible. Look, I’ll turn this around so you can see.

LONGSHOT in Mark’s phone as the screen flips:

ACTION: People running toward Molly, police cars, and other emergency vehicles, along with a new station’s location van heading away and down the street. The air is thick with smoke and there is still some fluttering debris descending through the, frame.

CLOSE UP: Mark. surprised face.

MARK

I’m just getting on the subway. Jesus! It’s like 9-11 again!

TWO-SHOT: Elderly lady sitting next to Mark throwing a look of rebuke at him.

MARK

You OK, Mol? You look scared.

CLOSE-UP: Mark’s iPhone. Returns to Molly’s face

.

MOLLY (voice shaking)

Jennifer has been recording it on her digital camera and is going to upload it to her Facebook page.

You might want to go and take a look at it. She’s thinking of posting it on YouTube, too.

CLOSE UP: Mark’s face.

MARK

I will. Hey, see if you can get some more video. Maybe this footage is something I can

use for my film project at NYU. But be careful.

CLOSE UP: Mark’s iPhone; Molly’s face.

MOLLY

I don’t know if we can. Maybe we should just leave. The police are saying it probably was a

bomb and there might be another one, you know, to kill the responders, but . . . [audible crackle]

CLOSE UP: Screen on Mark’s iPhone turns to snow static.

FADE TO WHITE

To photograph is to confer importance. There is probably no subject that cannot be beautified; moreover, there is no way to suppress the tendency inherent in all photographs to a accord value to their subjects. . . . In the mansions of pre-democratic culture, someone who gets photographed is a celebrity. In the open fields of American experience, as cataloged with passion by Whitman and as sized up with a shrug by Warhol, everybody is a celebrity. No moment is more important than any other moment; no person is more interesting than any other person. [Susan Sontag, On Photography]*

In the ability to fashion images, it seems that humankind has always been especially fascinated with itself, whether it is with those Paleolithic cave drawings, the bustle of turn-of-the-century streets, or the realistically or surrealistically imagined narratives of moving fiction. We are mostly fascinated with ourselves, perhaps because we are each in our own way a camera.

Mark and Molly, with their iPhones capable of digitally recording “real time” events, transmitting them to one another, uploading them to various forms of mass communication, “sharing” images only moments removed from their occurrence, are of course light years beyond a troglodyte tableau from crude brushes and pigments, or those grainy, flickering snippets of urban life documented by clunky locked down cameras in some turn-of the–century American Avenue. But the essences remain the same: life observed, made into images, those images examined, interpreted, dissected, manipulated, slowed down, speeded up, etc., to either understand its story, or to imagine one.

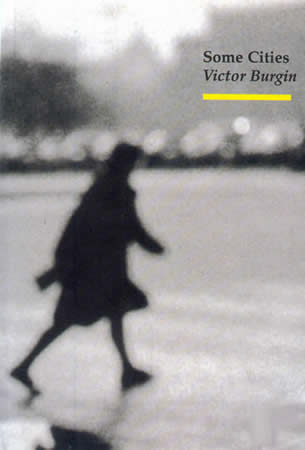

The cover photo of Victor Burgin’s book of his photography is illustrative of the photographer’s eye that seeks out what is mysterious in the seemingly most mundane of urban moments. In an Antonioni-like “blow-up” the blurry silhouette of a woman (girl?) strides across a space (street?) with only vague urban components in the distance. We only learn later that this nameless, faceless woman is a Varsovian on some unknown errand appears in the corner of a photo the author made of another, primary subject in Warsaw in 1981. But does she not represent untold urbanites in cities everywhere? One wonders in studying the photograph whether she has any recollection of a moment and place in her life that was chosen, albeit perhaps in afterthought, to stand for a body of work selected from nearly two decades of the author’s travels. Burgin forces us to think about her, and by extension, to consider the city.

The city has once again invented and expanded its technology of image making and its communication such that the capability to hold up an iPhone or a small digital camera and decide that something before us merits being framed and recorded, to simply give it a title, or a caption, and be a complete narrative or a clue to one.

With Molly and Mark the urbanite has evolved from the subject of urban cinema to an amalgam of writer, cameraman, director, editor, producer, and distributer. All that urban space for sound stages, movie theaters and heavy equipment is replaced by digital space and “imported” images and multiple terabyte computer hard drives and sophisticated movie-editing software. With the new image technology we all have become potential movie-makers.

But the iPhone, the point-and-shoot and highly portable video camera do not portend a technological determinism. Give a kid a point and shoot and we might get two-dozen pictures of a sleeping cat, and we have all sat in polite boredom at someone’s interminable and inane vacation video. Video games have yet to evolve from simplistic violent plots. The essence of the “captured” image is, as it always was, and always will be, what captures our interest—what we think the images “says,” not just depicts, what it represents, not is just representational, what its “story” is.

And the “story” is always imminent (and immanent) at the intersection of image and imagination. Jennifer’s shaky video of dust and debris rolling down a New York street is now immediately evocative of other “time-coded” images of the city. At times it seems the city can almost impose its narrative upon us. Movies that contain the New York skyline shot of lower Manhattan can now be dated or demarcated by the presence, or absence, of the World Trade Center. Moreover, those very structures continue to exist in a King Kong movie, and numerous others, and evoke or stand for movies like 9-to-5 or Wall Street. These iconic buildings become places “exposed” in our memories from actual events or what we have imagined in them.

Of course, this new, multiple–refractive reality between image subject and image-maker, has itself become the “story” of many motion pictures. The mere curiosity of observation has become transmogrified into what is considered to be the necessity of surveillance, seizing the urbanite as “talent” in daily documentaries of a myriad of cameras in shops, public buildings in spaces, elevators, and ATMs. We might, or might not, be a “person of interest” in some drama into which we are unwittingly captured. In many parts of the city we are never “off camera,” a new reality that it solve has become the subject of surveillance and surreptitious observation in films from The Conversation to Enemy of the State and Eagle Eye.

We not only capture images, but in an age in which we are virtually surrounded by images, many images are intended to capture us, or at least our attention from the mass of still and moving images we encounter in a single day.

What will be the effect upon creativity? With everyone a potential movie-maker with access to technologies that we only imagined in science fiction and comic books a generation ago, will the image be so trivialized by its abundance and ubiquity that we will come to regard it or ignore it out of a bored insouciance.

Not likely.

The City

Our relations with cities are like our relations with people. We love them, hate them, or are indifferent toward them. On our first day in a city that is new to us, we go looking for the city. We go down this street, around that corner. We are aware of the faces of passers-by. But the city eludes us, and we become uncertain whether we are looking for a city, or for a person. [Victor Burgin, Some Cities]**

From its very beginnings the great attraction of the city—serving its noblest purpose—has been its capacity to expand the possibilities for individual opportunity and self-expression. At its best it offers, sometimes out of exploitation, sometimes out of need, sometimes out of its sheer mass and anonymity, a freedom to be, to self-define, the highest achievements in the human experience.

The city, as embraced by this project, is our greatest subject. It is our most complex and important invention, the container not only of our art, politics, ingenuity, intelligence, and our dreams, it continues to fascinate, perplex and entertain us.

We began this exploration of the reciprocal relationship between the city and the cinema with a discussion of those earliest films produced in the streets of cities in the first decades of the 20th century, composed largely of voyeuristic curiosities of the commonplace circadian activities of American urban life. In its formative days the cinema of urbanism featured the activities of the same city streets that Molly emerges into today. A lot has changed in a century; and some essentials remain.

What remains is the dynamism of the themes that were chosen. Immigrants will continue to be drawn to the flame of urban opportunities like moths. They will look and sound different from Chaplin’s characters, but they will emerge as wide-eyed with wonder and trepidation, as they do in the final scenes of Crash as they did on first sighting the Statue of Liberty in America, America. The contrasts between small towns and the big city remains a viable theme for exploring the differences in American values, such as in New in Town (2009). A simple search in iMDB on “suburbia” testifies to the growth of both producer and audience interest, especially, in films such as Hesher (2010); Everything Must Go (2010), in rebellion against its oppressive norms.

As it did for years with Japanese monster films, the city, especially the large metropolis, will be punished (sometimes by remake) by giant monsters and space aliens (remakes of Godzilla, The Day the Earth Stood Still, War of the Worlds), climate change (The Day After Tomorrow), transformers, pandemics (Contagion) and end of the world predictions (2012) in the expansive theme of urban holocaustalism. Out of guilt or childish distemper we see always impelled to the theme of seeing our greatest inventions brought low by forces unleashed often by our own ungoverned impulses, entertained by it when it is the product of our own imaginations and abhorred by it when there is no necessity for suspension of disbelief.

Yet in those same cities we remain willing to believe that there is a Breakfast at Tiffany’s orMoonstruck love story in full bloom (or gone sour) in every other window in a apartment building, or Double Indemnity crime story in every other brownstone or lurking and gloomy alleys. We expect that there will always exist the dramatic frictions of rich and poor of Midnight Cowboy, the contending races and ethnicities of West Side Story, dreams alive on 42nd Streetand Sister Carrie’s dreams dashed, those on the way up for a Pretty Woman, or down in Bonfire of the Vanities, and the ever present sense that, in the city, something might happen: aPrisoner of Second Avenue urged by circumstances to rebellion, or a an attempted hit on The Godfather in Little Italy. There is always the molecular world of an immigrant Jew in Hester Street, or the rhapsodic sweep of Portrait of Jennie.

Every culture has its characteristic drama. It chooses from the sum total of human possibilities certain acts and interests, certain processes and values, and endows them with special significance: provides them with a setting: organizes rights and ceremonies: excludes from the circle of dramatic response of thousand other daily acts which, though they remain part of the “real” the world, are not active agents in the drama itself period the stage on which this drama is enacted, with the most skilled actors and a full supporting company and specially designed scenery, is the city: it is here that it reaches its highest pitch of intensity. [Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities]***

The cinematic city and the life portrayed in it as discussed in the preceding chapters are admittedly a subjective “take” on the subject. The topics chosen, the films selected––especially those chosen to typify their theme––owe everything to the author’s “time,” “place,” and “circumstance,” his own, particular, personal and peculiar urban chronicity. This is, unavoidably, to use the vernacular, “where I am coming from.” If those themes and reciprocities can be communicated, if there are commonalities and connections, or if they open possibilities, then there might be merit this effort in spite of the certainly of overlooking someone’s iconic city or film or perspective, as it surely must, then there at least remains a wider frame and always room for further exploration. This is not a treatise on the fixed body of work of a dead poet, but of a dynamic and mutating relationship of elements that grow and change both independent of and because of that relationship. Consequently, there is an inescapable subjectivity in the ramification of the screenwriters vision, the directors interpretation, and what particular focus of interest––in this author’s case, what this or that movie has to say about cities and urban life––that one can only hope can be expressed in a manner of some academic value, that adds perspective, provokes discourse, and incites further attention.

Or, will it push us further creatively, seeking that angle, that composition, that montage of shots, that mixture of sight with sound and speech, that cut that is so apt or revealing, that edit that composes something that says not only what is, but what it subjunctively might have been. It will probably always be there.

Perhaps when Molly and her friend emerged from a movie theater into a street in which there is a real drama unfolding that they are moved to document, the city and the cinema merge—the city becomes cinema, and it becomes a critical means by which we try to comprehend it ramifications. And as we urbanites are intensely conscious of ourselves as observers and subjects of images, fall into an existential illusion/synthesis in which we become the subject/objects of at least a sense of our own urban drama.

____________________________________________________________

©2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 9.10.2013)

Note: This essay is taken from the concluding chapter of my book, The American City in the Cinema (Transaction Publishers 2013)

*New York, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1973, P. 28

**Berkeley, University of California Press, 1966, jacket leaf. See also review by James A. Clapp,Journal of Planning Education And Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, Fall 1997, Pp. 109-11

***Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc. 1938, P. 60