“Some years ago, my father came home with a carton of old letters that time and humidity had compacted into wads of barely legible paper. He announced that he had found them in the attic of the old family palazzo on the Grand Canal, where he had lived as a boy in the twenties.”

“Some years ago, my father came home with a carton of old letters that time and humidity had compacted into wads of barely legible paper. He announced that he had found them in the attic of the old family palazzo on the Grand Canal, where he had lived as a boy in the twenties.”

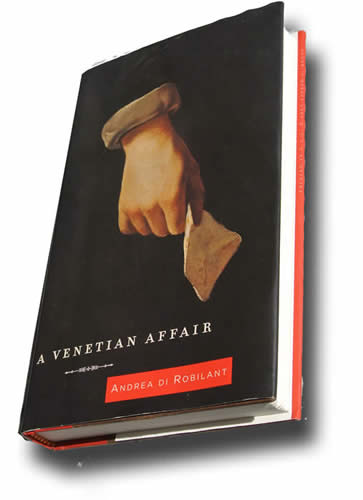

Some guys have all the luck; I love old letters, and I love Venice and, like probably every writer, I love a good story. So it was rather apt that as I was reading through the Venetian affair I took it to the local café of which I am an habitué, and happen to be sitting nearby a young woman who was texting on her smart phone the whole while I was there – hardly an uncommon sight these days. But it coincided strangely with another book that I had recently that I was reading because the letters that author Andrea Di Robilant’s father had discovered were predominantly correspondence between two lovers in Venice in 1750s. As that correspondence is translated and related as the core of this narrative two things become evident: one is that the back-and-forth correspondence between an English girl, Giustiniana Wynne, and Andrea Memmo, a young swain destined to become a great Venetian statesman.

This was all a premise worthy of Shakespeare (but he already did a story somewhat like this set just up the road in Verona), or any one of a number of contemporary bodice ripping romance novelists. But this was real! Well most of the elements were real. This cash of exchanges between two lovers of on even social rank –– he of the Venetian nobility, and she coming from some money and respected position –– reads a little bit like what would that have been the text messages of the mid-18th century. They are, as one might suspect and, as seems to be characteristic of communications put down by hand and pen, better composed, more erudite, and likely much more interesting than what would find these days thumbed out on a smart phone, although at times there is a tediousness in link the declarations of affection or suspicions of the decline of it. Another significant difference between these epistolary modes are that the Venetian lovers relied upon go-betweens and servants to dash through the streets and along the canals to deliver them.

It needs to be added that such a find of 18th-century memorabilia is enhanced by the fact that Venice itself is such a discovery. I can easily recall my first encounter with the city, emerging from the stars he own a federal Villa directly upon the grand Canal one early morning many years ago with the overwhelming feeling of being transported into the 14th century. Venice is a city that neither wishes, nor is able, to engage in urban renewal and land-use changes in the manner of many other cities. Constructed on a million or so larch piles driven into the mud of its Adriatic lagoon, there is little or no prospect for changes in land use to higher structural uses, particularly uses that are heavier. Even with its characteristic lacy “Venetian Gothic architecture,” constructed in a manner to minimize weight, the city resides a few scant feet above the level of the lagoon.

So Venice itself is the architectural equivalent of a find of 18th-century romantic correspondence in that one falls in love with it just as easily. So it is easy to imagine these two lovers who both were fully cognizant of the prohibitions and strictures of social class at the time, meeting clandestinely wearing the masks of Carnevale, or setting appointments in dark lanes, or in the apartments of trusted friends. Venice fairly oozes a sense of intrigue, secrecy, and the forbidden. Just see Don’t Look Now (1973), Nicholas Roeg’s eerie premonitions of Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland in La Serenissima. I myself had such an encounter a few years later. Patty and I visited the Ca Pescaro for a Giacometti exhibition on its main floor. It was just after opening in the morning and we were the only one’s there, a strange but pleasant feeling among the spare positioning of the sculptures in the spacious room.

But as we were about to leave the Palazzo, the lone custodian approached us to ask if we might be interested in seeing something of unusual interest. This was Venice of course, not some remote museum in someplace called Kidnapostan, so we said why not when he allowed that we could tip him appropriately after we saw the “something of unusual interest.” He then led us to a door that might have been to a closet but which opened to a dark rather steep staircase that ascended to a large, stuffy room that was dimly illuminated by small windows composed of circular pains of Venetian glass, and smelled of a spicy antiquity. We did not know at the time that we were entering the Museo d’Arte Orientale of the Ca Pesaro as we ascended the stairs past a phalanx of samurai warriors!, fully-girded for battle, including frightening face masks. They are part of an epic 1887–89 souvenir-shopping spree across Asia that Prince Enrico di Borbone preserved for posterity in vintage curio cabinets in his collection of 30,000 objets d’art. The collection has been left much as it was organized in 1928, with displays periodically covered to preserve against light damage.

One can only imagine how much fascinating material collects dust and molders in the attics of Venetian palazzi (forget about the basements, they’re full of water). And imagining is just what a number of writers have done. Donna Leon’s mystery novel, The Jewels of Paradise, centers on the discovery of two locked chests of a 16th C Venetian prelate-music composer. Unfortunately, after a couple hundred pages of foreplay this rather awkward story pays off in a dud of a denoument. Maybe that is also what a lot of attic junk turns out to be, but it is less forgivable when coming from a writer’s imagination.

The Venetian affair between Giustiniana and Adrea does not come to some neat chick-lit conclusion with their being sculled toward one another in separate gondolas to a satisfying embrace that spurns all she social impediments that frustrated their passion. Clearly, the romantic sensibilities of these correspondents is firmly established, but so also are their practical concerns. Perhaps, too, they were more acutely aware of the ephemeral reality of such passion, a passion that maintained its intensity, it seems, more by the very circumstances of its difficulty in consummation. So, while these lovers did find some fleeting opportunities to bring their obsession to physical completion, time, social position, and geographic distance eventually lead each to satisfying marriages with others. Perhaps, they lived out their lives reminiscing on their brief time of youthful ardor, reopening the memories as one might reread one of those old letters and giving the imagination leave to defy the inevitability of time.

________________________________________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.15.2013)