Out here in Hong Kong the BBC, beloved as “the Bebe” by some, serves as a largely reliable source of news and information for me. But every so often there is an bit of annoying “Britishness” in its broadcasts. Recently, it ran a piece about a professor from the London School of Economics who had devised a revision of perhaps that most annoying attribute of Britishness, social class, coming up with a seven-tierd hierarchy. One could, if they desired, go to the BBC website and fill in a survey with their personal information, to determine just where one “fits” in these social class categories. It’s a simple survey of a small number of variables, putatively relevant enough to assess one’s place in British society.

Out here in Hong Kong the BBC, beloved as “the Bebe” by some, serves as a largely reliable source of news and information for me. But every so often there is an bit of annoying “Britishness” in its broadcasts. Recently, it ran a piece about a professor from the London School of Economics who had devised a revision of perhaps that most annoying attribute of Britishness, social class, coming up with a seven-tierd hierarchy. One could, if they desired, go to the BBC website and fill in a survey with their personal information, to determine just where one “fits” in these social class categories. It’s a simple survey of a small number of variables, putatively relevant enough to assess one’s place in British society.

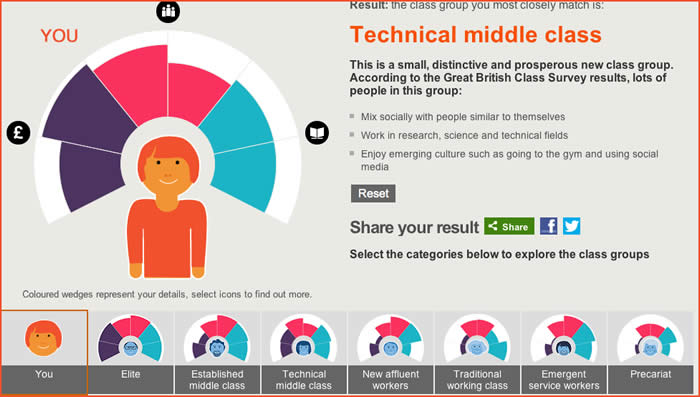

I took the test and, as the graphic above shows I came out in the “Technical middle class,” a “small, distinctive and prosperous new class group,” despite the fact that, in my own terms, “technical” is not a term I would consider using to describe myself. But then, unlike the Brits, what I’ve always found to be sociopathicly-obsessed with their class distinctions and positions, I am aggressively resistant to being defined by others. This is because there lurks in the fundamentals of the British social class system (as there does and other social class systems) a tendency for such systems to be themselves confined by those in the social strata who have arrogated to themselves a position of supremacy in the hierarchy based on some notion of superior bloodline or breeding.

This is why I cannot abide those denizens of the “upstairs” of the beloved Downton Abbey, the extremely popular latest British export drama of their beloved aristocratic gentry ingested by Anglophiliacs like fine a brandy after riding to hounds. Drama is, as we know, based in conflict, in contrast and difference make for much conflict, and often engrossing drama. The British class system as portrayed in Downton Abbey, provides a dramatis personae of upstairs insufferable twits, who are forever getting dressed for dinner and engaging in self absorbed, unproductive pursuits, like parties and hunts, and worrying that they might be doing something unbecoming being an insufferable twit. Not that I hold those “below stairs” in much higher regard, especially those who have completely bought into the notion that among humankind there are those who can be described as “betters” and “lessers,” and abide by the indoctrination that they should never ever entertain the prospect of “rising above one’s station.”

In sociological parlance that is not reflected in the simplistic BBC format referred to above, there are other ways of looking at the demographic phenomenon of social stratification. At the top of the British system is the small and rather elusive category of “elite,” a cohort that often achieves its exclusiveness from a self-definition of superior bloodline. They are the aristocracy, who have arrogated to themselves most of the land and property that allows them to live indolent lives that involve no labor, and in which they are constantly dressing for dinner. Oh, they are sometimes required by their internal codes of responsibility and honor to serve in the government or perhaps acquire a military (officer class only) title to add to Earl, Baron or Duke, but this usually only serves to enhance their precious sense of themselves. These are the sorts of people who take to themselves, or inherit (not merit) not only titles of social position and privilege, but result in the likes of the Royal Family, and flaunt escutcheons that announce “Dieu et Mon Droit,” to justify their authority to rule. And, as with most stratified societies the elites get more than their share of opportunity to propagandize, more than their share of good public relations.

Broadening my perspective on this subject beyond its relevance to the class obsessed British, nothing invites push back from me more than the attitude of some people that they are superior to others by virtue of race, ethnicity, gender or other circumstances of birth, such as nationality, over which they should receive either credit or blame. But given that we all called by these variables by the assignment of birth, humans are forever seeking reasons and means by which they can distinguish themselves in what can be called “achieved” or acquired status. Needless to say there are great prospects for bigotry, intolerance, and domination, among other nasty attitudes and behaviors in the establishment of social hierarchy. This is not to say that it is socially deleterious or inappropriate for those who wish to apply their talents and further their ambitions in ways that are not “hydraulic” to the commonweal or the interests of others. Society certainly could not advance otherwise.

But the ugly fact of human history is that much of the arrogated status of aristocracies and elites has been achieved at the expense of those which we have elsewhere referred to as the “laboring classes,” and the bourgeoisie. It is interesting that the class hierarchy in the BBC formulation contains at its bottom a coterie referred to as the “Precariat,” a most apt neologism for that category of humankind whose predicament can often be explained in good part as a result of the manner in which those at the opposite end of the social class spectrum have advantaged themselves.

But let us turn from this somewhat didactic tone to some appropriately illustrative segments of personal memoir germane to the theme.

London, 1979.* It was in an old pub nearby Trafalgar Square that I met Cecil, Thomas and Ned. They were “regulars.” I mean “regulars”; they’d been coming to this same pub since the 1930s. Pensioners for many years by now, they had spent their working life in government offices in nearby Whitehall.

Well, Ned didn’t. Ned was a dog; Thomas’ seeing-eye dog. “Ned, The Dog,” as he was called to distinguish him from Ned, The Bartender, was named after Edward I, the King who in 1291 erected the last of thirteen crosses that marked the stages in the funeral procession of his wife Eleanor to Westminster Abbey, giving the area near the pub the name, Charring Cross. Ned was always curled-up under the little table that held their mahogany-hued quarts of English ale.

Cecil and Thomas always sat on the ancient butt-worn dark wood benches on which I imagined people like Boswell and Dr. Johnson to once have parked. With the bare wood floor, greasy, smoke-tar encrusted beams, paisley velveteen wainscoting, and the light-restricting wavy window glass, the pub possessed all the dark, cozy, gritty elements I had seen in a dozen English period films.

I seated myself on the other side of the small fireplace that now contained a small electric space heater of little benefit. “Might you gentlemen happen to know the year this pub was built?” I inquired.

Cecil looked at me, but it was Thomas who responded.

“Seventeen-0-four, I believe,” he said, his eyes looking blankly into space. “Or could I confusing it with the year of your birth, Cecil?” he quickly appended.

“You no doubt remember well the pree-decessor structure,” Cecil fired back at Thomas. Then, turning to me he added: “You see, there was a pub on this site that was burned in the Great Fire of 1666. This is the ‘new’ pub.”

“Now don’t be giving the Yank a history lesson,” Thomas inserted.

“He did ask a historical question,” said Cecil.

“An historical question; don’t also be instructing him in improper grammar either.

I had overheard this sort of repartee between Cecil and Thomas on a couple of earlier occasions. They were the pub’s local authorities on English history and language, about which they mischievously liked to disagree.

I’d asked the question about the pub’s date chiefly to break the ice. Pubs can be genial places, but they also have almost a code governing discourse that steers away from personal data. In America the first two questions one is likely to ask or receive in making a new acquaintance are: “What’s your name?” and “What do you do?” This might be the reason why it has always seemed to me that English pubs were far friendlier places than their counterpart, the American bar. Consider the fact that telling strangers your name and occupation in an American bar gives them at least two bases on which to punch you in the face. Your name is likely to betray an ethnic heritage that your newfound bar friend associates with the rape of his great-great grandmother ages ago in some faraway land that doesn’t even exist anymore. Tell him your occupation and you divulge something about your education, how much money you make, and whether you are, say, labor or management. All these are good reasons for him to view you with envy, competitiveness, or to see you as one of the privileged creeps who worked his father to death and keeps him hovering around the poverty level. In an American bar such information is less likely to be the foundation for an amicable conversation than a causas belli.

In an English pub one can go a long time without such inquires, if they ever arise. This is not to say that there aren’t brawls in English pubs, but they are more likely to be over politics or football (soccer) allegiances. These dangers can be avoided by simply walking into a pub and not proposing a toast to the IRA, and by making sure that the color of clothing you are wearing is not the same as the team that cost a bunch of drunken hooligans a week’s pay betting on their team.

Applying this knowledge in the pub I had remained reticent until I could fashion a suitable icebreaker question. But even after we began a discourse, while I knew their names by way of my eavesdropping, I didn’t use them. They seemed content to address me as ‘the Yank’.

In spite of these ‘formalities’ we had interesting discussions on several subjects, principally related to Cecil’s and Thomas’ areas of expertise: English history and language.

I had been patronizing this pub for a few weeks up to this point, ever since the election of Margaret Thatcher as the UK’s Prime Minister. Normally the election of Mrs. Thatcher would have been of little personal concern other than my customary liberal’s lament at furtherance of the rightward course of political leadership around the world. In this case, however, the “Iron Lady’s” accession to high office had pulled the rug from under my research sabbatical. The national development tax legislation I had been studying had been installed by the now defeated Labor government. Mrs. Thatcher took little more than a few days to send the tax law, and my research project, into the “dustbin.”

With nothing left to study I had to come up with another research agenda. I elected to examine the ways in which English painters had portrayed cities and urban conditions over the course of the past few centuries. It was a project that seemed safe from the new Prime Minister until she got round to clearing or closing the nation’s art museums. In the meantime I would be regularly visiting the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, England’s most significant museum of art. The pub was a couple of blocks off the square.

While Cecil and Thomas did wonder if the Tory victory might affect pensions ands social programs they had seen enough governments come and go to view the matter without approval or alarm. Nevertheless I avoided politics in the pub. Over the weeks I frequented the pub at lunchtime we spoke mostly about history, language, and why Young’s Ale was the equivalent of divine nectar. One’s allegiance to a particular brew was about a personal as discussion would get. Even the subject of why this particular “yank” was in London in the first placed was never raised.

Cecil and Thomas knew a great deal about English history, if they did at times find grounds for disagreement for the friendly rivalry. However, I was mostly interested in the city’s history, and particularly the period with which both of the old gents had direct experience: the Blitz.

The British seem to have an almost benign tone to terms they employ for the prejudices. I am addressed as a “Yank” in a way that combines a familiarity with an undertone of British superiority. “About ten minutes by foot,” an elderly, clerkish man informed me as to directions to the “tube” station, adding with a grin, “about fifteen minutes for a ‘Yank’”. Even their racial and ethnic slurs seem less vicious than those of other nationalities. Argentines were referred to as the “Argies” in the Falklands War, creating the image that the British forces were subduing something like cuddly stuffed animals. Native Africans had been referred to as ‘fuzzy-wuzzys” during the colonial period. Not nice, but not nearly as nasty-sounding as the more universal epithet. Pakistanis became “Pakis,” but “wogs” is used by those of meaner intent.

On the other hand it might well be that such “diminutives” are the way the British make themselves feel a bit larger and more formidable than their contemporary national size and geo-political influence would dictate. After all the once great “British Empire,” or as one wag referred to its more ruthless methods of territorial acquisition, the “Brutish Empire,” is today a mere sliver of its former self. And although they earned great admiration and respect for almost single-handedly saving the world from having to learn to speak German in the early 1940s, they came out of things so weakened that their imperial days were virtually brought to an end.

Indeed, that period, the time of London in the Blitz, the time of those grainy newsreels in the movies and Ed Murrow broadcasts during bomb raids, that was the time when the British earned my admiration, and was the period of London’s history that most fascinated me. I prowled the East End and docks areas, now undergoing “gentrification,” looking for clues of those nights when Heinkle 111s droned overhead disgorging incendiaries, and V-1s and V-2s plunged into the neighborhoods around St. Paul’s Cathedral. In the Underground I could imagine families sleeping out the raids on the platforms of Piccadilly or Oxford Circus stations. For me the train sheds at Victoria or Kings Cross were just a mnemonic click away from the throngs of troops saying their emotional goodbyes. I returned time an again to the Imperial War Museum and the restored aircraft of the Battle of Britain Museum on the site where Hawker Hurricanes and Spitfires scrambled into the air and later B-17s and Lancasters lumbered off with their bomb-loads for Germany. Despite the Wimpy restaurants, contemporary products on the neon signs at Piccadilly Circus, ugly Council Housing and the wretched architecture that so upsets Prince Charles, despite what remains of Roman, Elizabethan, Dickensian, or the other “Londons” of the past, for me, the most historically-evocative London is the London of the Blitz.

“Have you paid the War Rooms over in Whitehall a visit?” Cecil asked me. “That’s where you will find things pretty much as they were during the air raids.”

“Churchill’s desk and bed are there, just as they were when the war ended,” Thomas added. I wondered whether he had always been blind, or was speaking from having seen them himself.

“It’s hard for me to imagine what it must have been like in this area in the early 1940s,” I said.

“You ‘ad to mind your ‘P’s and Q’s’ in those days. We kept things as dark as possible, especially in this part of the city. Goering would’ve loved to put a few 500 ponders in the middle of Whitehall.”

“Better tell the Yank about the ‘P’s and Q’s’,” Thomas said, lifting his glass and pulling the mahogany-hued nectar through the thin layer of foam.

“In the first war there were some people who worked in the munitions factories who liked to relax in the pubs. Then was, of course, when pub hours were set to closing at eleven in the evening. But just to remind the workers returning to the late shifts in the munitions plants of the incompatibilities of alcohol and explosives, they used to put up signs in the pubs to ‘mind the Pints and Quarts’. Pints and Quarts, you see, “Ps and Q’s,” he said a trifle condescendingly. “It was also good advice for anyone, as one could have an injury bumping into things and tripping over things in the dark streets, especially with a bit fog in the bargain.”

Again I wondered if Thomas had been blind during the war, or maybe made blind by the war. The blackouts would have had little effect on him.

“Maybe you would trip over some Yank givin’ it t’ one of our English girls right on the street,” Thomas put in. “They’d be shagging standin’ up, right in the doorways of closed shops, and up against buildings and trees. You Yanks call it givin’ a girl a ‘wall job’ and they’d less likely get pregnant doin’ it standin’ up,” so they said. He related this stern-faced and, with his use of the present tense, I felt like I was some B-17 waist gunner with a three-day erection and a three-day pass to go with it. By his tone and expression I might have just de-flowered his sister up against the side of Westminster Abbey.

“Love ‘n war, mate,” Cecil said, “ it was love ‘n war.”

In spite of the little jibes and put-downs I enjoyed my lunchtimes with Cecil and Thomas. We were almost approaching what, in British terms, could be regarded as “familiarity.”

Then it all came to rather an abrupt end.

It was after a couple of months of lunches and a good many “Ps and Qs” that in a conversation I casually mentioned “at my university” in reference to some point I was making. Cecil and Thomas both “looked” over at me as though I had spoken something insulting to the queen. I think even Ned roused to fix his gaze on me.

“Your university?” Cecil asked.

“Yes, in southern California, San Diego. I’m a professor there,” I replied innocently. I waited for the customary question: What do you teach? But there was just a slightly awkward silence.

Then Thomas asked, fixing his look to approximately where my voice was coming from, “Why, then, are you not drinking at your club?”

I laughed, saying that the grandson of an Italian farmer who went to America in steerage had no intentions of ever being a member of a club.

But things were never the same after that. The British class system had closed down like heavy curtain between me and my newfound pub drinking mates. There was a less familiar tone in their greetings and they were less forthcoming in conversation. I soon began taking my lunches at the Italian tavola calda closer to the museum.

Another anecdote further documents the social class theme, from the same period I was living in London.

Mornings and Knights in Hyde Park. In the photograph I am standing on the steps of the Albert Memorial. Wearing sweats, a knit watch cap, sneakers and gloves, I look a bit like Sylvester Stallone in “Rocky.” The snapshot caught the steam from my breath and the penumbra of condensation forming around me. It was damn cold in Hyde Park that morning. A few days earlier my daughters and I had made a snowman over by the little pet cemetery along Bayswater Road.

My wife, Patty, had taken the photo. An artist, she had come to the park with me around 6:30AM to shoot some photos for her work while I ran my three-mile route from Kensington Palace (most renowned of late for being the last residence of the beloved Princess Diana) in the West, to Wellington’s old residence (Apsley House) in the East, weaving around the Serpentine pond in the middle.

Running, or walking, through Hyde Park is a brief journey through English history. It was originally the hunting preserve of Henry VIII. James I opened it to the public and Queen Victoria opened it to “all respectably dressed persons” (in which this James was in clear violation) when she added Kensington Gardens to the park. Since then it has seen artillery emplacements in both the Civil Wars and WWII installed and removed, and has been decorated with statuary and monuments to England’s royalty military heroes, and other builders of her empire.

We were living in Leinster Gardens Court, just north of the park in the Bayswater area. The daily run had become a virtual necessity if I was going to survive my sabbatical in London. It didn’t matter how cold it got in London that winter back in 1979, I was, so to speak, running for my life.

My life was being imperiled by English food.

Many people with functioning taste buds and gastro-intestinal tracts regard “English cuisine” as an oxymoron. Such people head directly for the nearest Indian, Chinese, Italian, or French restaurant at the first sign of hunger. These days I pretty much follow suit when I’m in the U.K.

But back in 1979, for reasons that remain mysterious to me, I got hooked on English food: English breakfasts, and Pub Grub, particularly fish and chips. One theory for this affliction is sort of “genetically” based. Being of Italo-Greek heritage I have hypothesized that my ancestors might have been in those Roman legions back in the first century B.C. that conquered “Brittania.” Many of them settled in the inclement little isle, intermarried with the locals (after the obligatory period of pillaging, raping, and other routines of the Pax Romana), and no doubt, began eating English breakfasts and other local delicacies.

Anyone who has survived an English Breakfast will recall that it probably consisted of the following: Bacon (though unlike American bacon, this is really more like boiled ham with slabs of translucent fat attached); Eggs, “runnyside-up,” and floating in the grease from the bacon; Hash Browns, cooked in . . . , you guessed it. And, to make sure that you are not missing your minimum lifetime requirement of fat and cholesterol, there are “bangers” (English sausages). Remember that no fat is permitted to be wasted, so the remaining fat is used to—are you ready for this?—deep-fry your toast! There might be a lonely half-stewed tomato as a gesture to one of the other food groups, or in some cases, and oily “kipper,” which is sort of an oversized smoked sardine. Wash it all down with tea with whole milk, and you are ready for a day in the “loos” of England’s tourist sites, or a test of Britain’s socialized medical system. You have just had perhaps the most mis-named meal in the history of cuisine: The Hearty English Breakfast.

My theory also posits that the Romans left Britain after a few hundred years because their Mediterranean blood chemistry couldn’t handle English cooking. The Romans conquered only as far north on the island as Northumberland, up near Scotland, then sort of gave up on the place. Historians say it was the weather, or the ferocious local tribes, who sent the Romans back south. But you have to have tasted “haggis” to know the real reason they left. There’s a long wall in Northumberland that marks the limit of the Roman northward advance. It still has some Roman communal toilets that were built into it, not doubt mute testimony to the Romans’ aversion to the apt sounding concoction of inadequately-cooked, weird animal organs, wrapped in intestines. Could the name have been derived from “gag us?”

History does not record how many Romans were killed off by Hearty English breakfasts and haggis. If they had blood chemistry anything like this descendant, their serum blood cholesterol jumped up ten points per mouthful.

To make matters worse I also had this inexplicable urge for English lunches and dinners, too. Pub lunches of bangers, Scotch eggs (hardboiled eggs sealed in a deep-fried carapace of doughy substance), Cornish Pasties of chopped meat in deep-fried dough (not mammary decorations), were favorites. For dinners I gravitated to fish and chips, a meal that totally reverses the arterial benefits associated with eating fish, and an occasional visit to a “carvery,” where one comprehends fully the origin of the term “Beefeater” in a atmosphere that only slightly civilizes what used to be Mediaeval gluttonous revels at which greasy-bearded trenchers flung joints of meat across raucous castle dining halls.

Since those days of running for my life in Hyde Park I have taken more to heart the advice and admonitions of the Surgeon General than I have allowed my stomach to try to digest hearty English breakfasts. When I think back on it there is little wonder why I ended those morning runs in Hyde Park with that little victory dance on the steps of the Albert Memorial: I’d survived another day of English cuisine.

But before I had taken my little victory dance on the steps of the Albert Memorial I had been pushing my reluctant body through Thames-hydrated air that was “cold enough to freeze Tiny Tim’s crutches” as Thomas had remarked at the pub a few days earlier. By the time I reached the entrance to the tunnel that snakes along the side of the Serpentine Pond in the middle of the park frost from my exhalations condensed and froze on my beard. Steam smoldered from my sweatshirt like I was about to burst into flame. I was sucking air like a fighter jet. I must have looked and sounded like some surreal beast, bundled in my sweat suit, watch cap pulled down to my frost-encrusted eyebrows, as I entered the dark opening of the tunnel.

The tunnel has a slight curve, and midway through, at six in the morning there is almost no light. This morning I was brought up short a few meters in by a strange sound, and odd metallic, clanking sound, coming from up ahead, around the curve and out of sight.

I stopped, jogging in place, allowing my eyes to adjust more to the low light, and lifting my cap off my ears to take in more sound. It had occurred to me on earlier runs that this place, at such an early hour, would be a good place for a mugging, or worse. Now the clanking was combined with a squeaking metallic sound. I considered turning around and not using the tunnel today. But I was also curious.

Slightly picking up my pace, and holding my breath so I could hear better I pushed on forward. The clanking grew louder, reverberating off the stone tunnel walls.

I was perhaps thirty meters away from its source when the light from the far opening silhouetted a figure, moving awkwardly, and slowly in the direction I was headed. The clanking and squeaking of metal grew louder.

When I got closer I could scarcely believe that the cold and A knight in a full suit of armor, ambling along using a halberd as a walking stick.

I pulled up again, jogging in pace that allowed me to maintain distance and collect my wits. I considered again turning about face and getting out of the tunnel. That halberd was a vicious weapon.

But I doubted that the knight even knew I was behind him, with all the clanking and squeaking of his armor, and his head in a full metal helmet. My heart was beating faster, but my wind had returned. I decided I would put on a sprint and blow by him at speed before he even knew I was there.

I was only a few feet beyond the knight when I heard someone yell: “You there, runner . . .” It was coming from a small group up ahead that I had not seen because of the curve of the tunnel, a camera crew, walking backwards.

“You there, runner, stop a moment, please,” someone called. I pulled up, jogging in place. “Would you mind just jogging alongside sir knight a bit while we get a shot of you both together.” The knight was clanking his way up behind me, but my heart already told me that my fear and flight instincts had abated. The crew was about ten meters ahead of us.

“Sure, OK,” I said.

Another voice asked, “Are you a ‘Yank’?”

“Yes.”

“Good.” But I didn’t know what ‘good’ meant.

Now the knight and I were side by side. In the better light I could see that he wore a genuine suit of armor. His face plate was pulled up, but I could only see his eyes. The crew had now come closer and the soundman held a short boom mike above our heads.

As though on a rehearsed cue the knight said: “What sort of damn fool yank is out here on a freezing morning running about in his underwear?” I could see the frost on his faceplate, and the voice had a noticeable shiver in it. But, of course, it was me, a yank, who was the damn fool to be out here, not an Englishman freezing to death in a metal suit.

As I jogged alongside I learned that ‘sir knight’ was “on a crusade,” a “circumnavigation” of the Serpentine in armor, attended by a television crew, to draw attention to the cruelty of “canning” in English schools.

“Canning!? You mean like in Dickens . . . ?” I asked.

“Taking a switch to a lad’s ahss for misbehavior,” the knight finished my thought. I had no idea such practices still existed.

“It’s a good cause, but your ass won’t be able to feel anything by the time you’re out of that armor.” I said. But he ignored the riposte.

“We’ve got enough,” the director said, “you can be on you way, yank. Look for yourself and sir knight on the news this evening.”

Dismissed again, I broke into a stride. Behind me I heard the knight shout: “Ban the cane! Ban the cane!”

I picked up my pace, feeling a second wind. The damp morning air wasn’t as biting as I rounded the end of the Serpentine and headed towards Wellington’s house. I felt better. Caning? In 1979! We “yanks” didn’t seem like such “uncivilized” former colonists after all.

And we don’t distort everything through the prism of social class.

__________________________________________________________________

© 2013, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.9.2013)

*Excerpted from “Once a ‘Yank,’ Always a ‘Yank’, in James A. Clapp, The Stranger is Me: Travels and Self-Discoveries,” 2007.