©1997, UrbisMedia

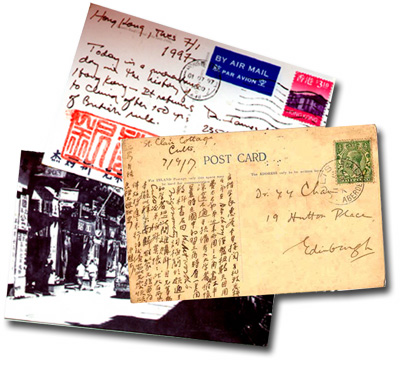

In 1997 I bought a tattered old postcard from a street vendor in Hong Kong. Its postal cancellation mark reads July 1, 1907. Addressed in faded ink to a Dr. Chan in Edinburgh, Scotland, the message side is crammed with vertical Chinese ideographs. The profile of King Edward VII adorns the “hape’ny” (one-half penny) postage stamp. Somehow, sometime, the card made its way back to Hong Kong, perhaps with Dr. Chan.

Surely this postcard got to Edinburgh by steamer, maybe taking months to reach Dr. Chan (doctor of what, I wonder?) in his cold flat where it warmed him with some “news from home.” But how did it get back to Hong Kong? As part of his personal effects? By ship, or later by plane? And When? And where has it been all these years, during two world wars, the rise of Hong Kong to a great world city? Did it sleep away some ninety years in an attic somewhere, a desk drawer, tucked in a book? And how did it end up with a street vendor of philatelic flotsam?

There’s s snapshot of some past lives retained in that old postcard; like the way a fossil retains something of its “author”. It’s a record of a time and sentiments gone by. That postcard is a relic of a medium of communication that I couldn’t help but contrast with my laptop computer, which was with me to assist in my work over a few months in Hong Kong. The computer would also be my primary mode of communication with family and friends back home. For the first time in a couple of decades of travel I would be “on line”. No more trips to the post office or Amex; my new mode of communication would be “modem communication”.

It is difficult to gainsay the ease and speed of E-mail. Each day I would log on and read mail from my daughters, or various friends, keeping current with affairs at home as if I were in fact “at home.” I could even set up a private chat group with family and friends and exchange news in real time. And E-mail became especially valuable when my father had a serious illness and I needed to be in close contact with the family.

But as with most technologies there is a down side: The magician has his price. For me, so much of the allure of travel is related to being in a different time and place. The ubiquity of cyberspace, and instantaneous communication through it, remove some of the sense of geographic and temporal distance. The low cost of E-mail means that the mundane and trivial matters that used to be left behind now can follow one around the globe. Did I want to be reminded about that root canal appointment after having spent an afternoon exploring Kyoto?

Then there is what might be referred to as the “aesthetic” of traditional (or “snail”) mail. Electronic mail just doesn’t lend itself to certain sentiments. The kinesthetic of typing is not at all like putting pen to paper, and selecting “bold” and “italics” for “I love you” seems like the equivalent of sending plastic flowers. Adding a typed smiley-face doesn’t help either.

E-mail is mail stripped to its essentials and. in the end, most of us dump it or leave it buried somewhere on our hard-drive. It’s mail that hasn’t had the experience of actual travel; it hasn’t been canceled, and shipped, fondled, mangled, and carried around in a pocket for days, or used as a book mark. Email may have content; but it lacks substance . There’s no coffee spill on it from that cafe in Sienna, no stamp that says Marrakech, or Djakarta, no envelope from The Hotel Metropole, or a postcard picture of the place to which the words “wish you were here” actually refers.

I’ll probably continue to travel with my laptop and modem, but I won’t be leaving my pen at home either. I rather like the idea that somebody in the year 2073 might discover one of my postcards in a street stall in some foreign city and wonder, as I do about Dr, Chan, what dimension of time and space its author might be traveling through.

___________________________________

©2003, ©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.12.2004)

Originally published as “Messages Bearing Music,” DimSum , Volume 7, Spring 2003