Last night, on TCM, I found myself watching––again––The Song of Bernadette, the 1943 movie about the little peasant girl of Lourdes who started seeing “a lady in white” in a grotto by the town dump. Why? I say again because I don’t know whether I used to have this sexual fascination with Jennifer Jones, who reminded me of my fifth grade nun, Sr. Mary Sharon, about whom I had the same fascination; or, whether I have some latent, unresolved thing about nuns in general (I understand it’s a porn thing with some guys). But if I get into that it will be one too many layers for this narrative to handle. I’ll just promise to get some counseling for all this, later.

Last night, on TCM, I found myself watching––again––The Song of Bernadette, the 1943 movie about the little peasant girl of Lourdes who started seeing “a lady in white” in a grotto by the town dump. Why? I say again because I don’t know whether I used to have this sexual fascination with Jennifer Jones, who reminded me of my fifth grade nun, Sr. Mary Sharon, about whom I had the same fascination; or, whether I have some latent, unresolved thing about nuns in general (I understand it’s a porn thing with some guys). But if I get into that it will be one too many layers for this narrative to handle. I’ll just promise to get some counseling for all this, later.

However, I do want to divert for a few paragraphs on the matter of nuns in the movies, a subset of cinematic curiosity that is shared by a good half dozen guys (who also probably need counseling) on the planet. I think you have to expect this sort of thing when impressionable young boys are turned over to the first non-mommy authoritative women in their lives to female penguins wielding two-pound crucifixes with mace-like lethality. Well, anyway . . .

So, back to the movies, and a question that yet haunts the minds of those young boys since grown up: who is “the best nun?” [Yes, I do mind if you go off and check your email or text messages now . . . your loss.]

First we have The Song of Bernadette (1943) with Jones, at 24, playing a teenager (but she had those permanent ingenu-ish looks; see Portrait of Jennie). We don’t get to see her in habit until late in the film, but she prepares the rest of the time wearing a peasant veil and comporting herself with such unassailable piety that she disarms a doubting priest, the town doctor and eventually everybody else even if none of them can only “see” the beautiful lady in white” by way of some alleged “miracles.” If you want to find some sensuality in Jones’s Bernadette you have to impute it from one of her other roles (maybe Madame Bovary, or Duel in the Sun). But she remains in the running for “best nun.”

Then there is Ingrid Bergman in The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945) playing this sort of sublimated sinful thought script with Bing Crosby as Fr. O’Malley. (Come to think of it, Bergman probably looked more like Sr. Mary Sharon than the others.) Bergman was aged thirty at the time and looking very “prima,” although this time she is rather self-assured as Sr. Mary Benedict, not the conflicted lover in Casablanca or the dominated wife in Gaslight. Clearly, the best part of the movie is her teaching a bullied student how to box.

By 1959 Hollywood was more willing to address that there was complexity to Jesus’ bigamous relationships with pretty, young nuns in The Nun’s Story.* That’s how it is for Sr. Luke (Audrey Hepburn), the last of my three candidates for the Sr. Mary Sharon of my blasphemous fantasies. I end up voting Audrey the “best nun” probably because she decides to leave after the order refuses to send her back to work on tropical diseases in the Congo and refuses to renounce the Nazis I (who killed her father in the Resistance).

Now we come to the postulant nun, Mariette Baptiste, the subject of Hansen’s novel about a rather anachronistic convent of an order of Belgian nuns in Upstate New York in 1906. Unlike the nuns of our movies, this is one of those cloistered orders that entirely renounces “the world” for a life of simple labors, orderly days, prayer, gossip, boredom, and the various forms of insanity that come with institutions that are founded on a bedrock of fantasy.

Now we come to the postulant nun, Mariette Baptiste, the subject of Hansen’s novel about a rather anachronistic convent of an order of Belgian nuns in Upstate New York in 1906. Unlike the nuns of our movies, this is one of those cloistered orders that entirely renounces “the world” for a life of simple labors, orderly days, prayer, gossip, boredom, and the various forms of insanity that come with institutions that are founded on a bedrock of fantasy.

Marie’s father is a physician and her sister is already the Prioress of the convent. (As myself a father of two daughters I cannot help but wonder at what it would be to bring them into this world to waste their lives in self-indulgent preparation for a delusional afterlife.** But, hey, that’s just moi.) So lovely little Mariette joins up and Hansen creatively leads us through a process in which the cumulative circadian rote of convent life can sap members of this ersatz sorority of all womanhood, or drive it inexorably to forms of sexual fantasy masquerading as holiness.*** I particularly appreciated the manner in which he renders the sort of twisted reasoning that comes from this sort of context. In a “scene” in which Mariette is with her confessor, Fr. Marriott, she has already confessed being disobedient by innocently imitating one of the other nuns. After Marriott tells her, . . . “just imagine how it hurts Jesus to see you making fun of these holy women that he loves so dearly.” He then asks her about her other sins. Picking up from Hansen:

She hesitates for a moment and tells him, “I have not been getting consolations from the mass. I have too little faith or fervor. I feel almost forsaken by God. Spiritually dry.”

Pére Marriott says. “We hear this from the holiest people. Even as far back as Isaiah we read, ‘truly, you are a hidden God.’ Even Jesus at his death cried out, ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?’ My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? We have to be patient at times we must permit God to rest in our presence. We have to believe that our good God not only loves us but is that which is most intimate to us. And if we truly need Him, there He’ll be. We can always rely on that.”

“Merci Bien, Pere Marriott.”

Later on, Mariette gradually is taken by her desire to be more pious and more intimate with her “husband,” to acquire or affect, with physiological evidence that appears and disappears and, with the shock of the premature death from cancer of her sister, the prioress, the stigmata of bleeding, wounded hands, feet, and side. That this throws the convent into a quandary—as though the reality of a physical manifestation of piety (or psychosomatic inducement) is too much to handle—that can only be resolved by denial and banishment.

There is another question to be broached here with regard to the way in which Christian, particularly in this case Roman Catholic, lore and dogma, pervert the sexuality of its adherents both clerical and lay. Probably the best way to express it is in that quirky way in which nuns become “brides of Christ.” When you’re a young boy who has a thing for his fifth grade teacher, Sr. Mary Sharon, but at the same time are told that she is a “bride” of a “resurrected” first century Jewish Rabbi, it kind of plays with your head. Consider how Hansen puts this thought-voice in Mariette’s head when she is punished for presumably affecting the stigmata: “Mother Sainte-Raphael has forbidden me Communion for six days now. Oh, how I ache for him, and how tortured and sick and desolate I have felt with out him! I grieve to imagine how dull and haggard and ugly his Mariette must seem to him now! And yet I should think myself hateful if being deprived of him for these six days had not grossly disfigured me. [Then, directly to her “lover/husband”] What a cruel mistress I am to complain so much about your absence when I should be wooing you and praising you for your kindness and sweet presence.”

Yup, I think I get what’s goin’ on here.

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 6.17.2012)

*It is worth noting that there are more examples of the prettified portrayals of convent life, for example, among my favorites are: Lillies of the Field (1963) in which an itinerant black handyman, Sidney Poitier, forms an affecting relationship with a bunch of East European nuns resettled to the American southwest; and Green Dolphin Street (1947) in which a guy loses the girl he loves to booze and Jesus (but that’s the way, Jesus probably had it all planned out). More recently there is The Doubt (2008), although there is no doubt that Meryl Streep does such a masterful job at playing a desexualized Sr. Aloysius Beauvier, the principal of the Catholic school she oversees, that she is definitely not a candidate for “best nun” for my sister Mary Sharon fantasy.

**To be fair there are, and have been, many nuns who have given selflessly of themselves in the service of others as nurses and teachers, often paying further suffering rape, torture, or assassination but, at a minimum, their exploitation by the Roman Catholic Church.

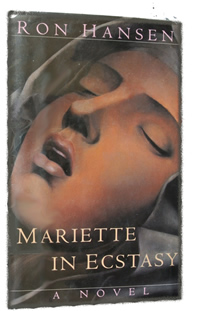

***It is appropriate that the jacket illustration is obviously derived from Bernini’s St. Therese in Ecstasy. See 13.5.