There are a lot of people who are bibliophiles, and a lot of bibliophiles who acquire a large number of books. Then there are bibliomaniacs that might have a hoarding complex. I think that might be me.

There are a lot of people who are bibliophiles, and a lot of bibliophiles who acquire a large number of books. Then there are bibliomaniacs that might have a hoarding complex. I think that might be me.

My attitude has long been that one can never have enough books; but that attitude doesn’t always square up with the amount of space you have to accommodate your mania. I’ve always envied the library that Prof. Henry Higgins had in the movie of My Fair Lady, the one with the staircase to a second level and the special ladder to access the upper shelves, all in mahogany. But in my cozy condo I have reached the spatial saturation point. There are books in nearly every room, one of which is entirely devoted to them, and they are of course in my office, but also there are several shelves in my bedroom. I love books; I have since I was a young kid. They are always there to company and entertain you, they make no reciprocal demands, and they take you away to faraway places in the past and future.

I don’t know how many books I have and, in spite of occasionally pruning my library and donating them to the public library, I almost immediately refill the shelf space with new acquisitions. I think this reveals an insecurity—that I might need to know something, or want to refer back to a book that I read, or some other such need, that I’m loath to part with my books, and always feel that I need to fill some lexical void with yet another book.

Ironically, although I resisted the idea of reading books on a digital device, what eventually urged me to purchase a Kindle was my other passion, travel. The logistics of travel are much influenced by the matter of weight these days. I go out for lengthy periods of time and that means heavier luggage. So when the airlines reduce the allowable weight of checked bags from seventy-two to fifty pounds I was forced to make choices between books and my necessities of Parmesan cheese, a pound of coffee and a jar of peanut butter. Books are heavy. And so on this last trip, when I would be out for over two months and in eleven countries, I opted for the Kindle––less than 10 ounces that can accommodate over 1000 books.

The Kindle also addresses that concern of insecurity that I might not be able to access a book or forget about 1 that I had made the intention to read someday. At Amazon, or at other sites that make digital books available, I can set up “wish lists,” the virtual libraries of my own where all those books that I intend to read, many of which I may never get around to, are “stored.” But these volumes do not require heavy bookcases that take up space and hold actual books that get dusty and brittle, and even lost behind one another and difficult to find.

We owe all of this to the digital revolution and the Internet. These days you can get almost anything––and I mean anything––that’s out there with a few clicks. It was recently announced that the Encyclopaedia Britannica that we used to appeal to in our local university library, that expansive set of heavy volumes that seemingly contained all knowledge, will no longer be sold as physical books. If you want to use the Encyclopaedia Britannica you have to subscribe the digital version on the Internet. The last few hundred book sets will be sold to traditional booklovers, but all the updates will take place on the Internet. So while I have several shelves of reference books, most of them have been already made out of date by materials available on the Internet. The Internet has also made my extensive reference library, accumulated at some cost over many years, all but obsolete.

The physical book may never fully fade away, but we have already witnessed the departure of many bookstores, places where I have spent a delightful and countless hours rummaging through shelves in search of specific subjects or titles, or just waiting for some literary surprise to call out for me to take it home. The older, used bookstores were a particular favorite haunt of mine and I can remember as I look across titles on my own bookshelves exactly where and when I purchased them: a history of science from Foley’s in London in 1977, or a book about great sea voyages at an intimate bookstore in Charing Cross Rd., the street of bookshops memorialized in the wonderful mood be about books, 88 Charing Cross Road; a title called Jesus Scrolls that I picked up at the English bookstore below the Keats House in the Piazza di Spagna in Rome that I remember devouring in a day on the train up to Paris; that reminds me of an old, and compact hardbound copy of Le Tour du Monde, in French, that I picked up for a mere twenty pence from the sale shelf outside a small booksellers in Salisbury New England, that I used to try to get my Francais up to speed. I could go on because I searched out and rummage through bookstores everywhere I traveled, especially the small used bookstores that might have a treasure that I have always sought, or one that I didn’t even know existed, lurking on a dusty shelf in the dim light. But the point is that these physical books are as much souvenirs, physical reminders of times and places in my life as much as they are vessels of knowledge and imagination.

The Kindle will also not give me the thrill of reading a used book in which I might stumble upon, as I have, an old letter or postcard that was used as a bookmark and forgotten when the book was sold or whatever fate that it had. I like the idea that someone else had turned those pages before me; I liked wondering where they were when they read it and what they thought as they read the same words.

The Kindle will not provide thrill of finding a first edition. The Kindle will also not lure a curious passerby into a conversation at a café or on a plane the way the cover of an actual book can. I will not be able to tuck and aerogramme or a postcard from a friend into its “pages” (although e-mail may well be resulting in the disappearance of those epistolary forms).

And what is to become of that other favorite haunt of mine, the library? The day may well come, and not before long, when the ambience of the library, the floors and rows of shelves, the student flopped on the floor reading, that rustling in the quiet, that moldering, paper-induced aroma of knowledge. Already, long gone are those banks of Dewey decimal system card catalogs, and students diligently copying out information for a research paper have been replaced by the credit card operated clunking photocopy machine. The Kindle and the digital book might well consign the library to the role of a “hard drive” that retains the remnants of a bibliographic form that is more museum of an aesthetic than it is a necessary technology.

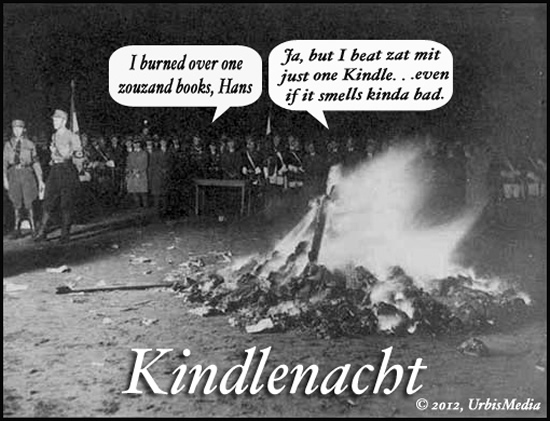

Since the days of the rolled papyrus papyrus through the time at which monks laboriously and beautifully copied out the prevailing knowledge in manuscript books, up to Gutenberg, people that love books. But because books open minds to knowledge that authoritarians have always liked to control, or because books espouse new ideas that challenge the old ways and the entrenched values and interests, books have also been despised by governments and religious institutions.* The Romans torched the bibliotheque at Alexandria (as Alexander had torched Persepolis), and there have been book bannings and burnings through the ages. But maybe when the next book burning comes about there will be, slightly illuminated by the flickering flames emitted by those venerable old volumes, a face in the background with a smirky smile and a loaded Kindle snugged in his back pocket.

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.26.2012)

*See Ray Bradbury, Farenheit 451; Umberto Eco, The Names of the Rose. Both have been made into movies if you do not have time for them in your reading plan.