Kodaks (sic) sign photographed by author in Burg al Arab, Egypt. © 1991, UrbisMedia

Their corporate image was only slightly less ubiquitous than Coca-Cola’s, eye-catching crimson and yellow brand. Kodak. For people around the world it meant snapshots, 35mm slides, and badly exposed 8mm motion pictures. And the big screen. But for people in Rochester, New York, where founder George Eastman established his company back in the 19th C it meant local philanthropy, endowed educational institutions, spinoff industries in optics and imaging, recreational activities, and a beneficence company town ambience for up to 60,000 employees and their families.

That was then, “back in the day,” as the current cliché might put it, and then came the rather precipitous decline, the poor decisions, plant closings, and the final ignominy of bankruptcy. Were it not for the like fates of other iconic giant American industries such an occurrence might be jaw-dropping. Sic transit Gloria mundi.

The image that Ronald Reagan and other conservative politicians were and are prone to invoke when they hearken to those good old days of an America that will never be again (if it ever truly was) is of a nation economically muscular with the sinews of manufacturing.—industrial America. They are the days that can only be recollected by a generation who were the last to have any direct contact with it before it faded, corroded or was shipped off to China. Dads going off to work carrying a lunch bucket with sandwiches made by a stay-at-home wife, walking or taking some mode of public transit, to factories with assembly lines that––and here’s the key word––manufactured things. These were industries whose workers were––and conservatives don’t like to recall this part––often unionized, that bloated their muscular might often on the steroid of war. Cities were proud partners in the process of manufacture and half a decade ago it was not uncommon to find civic stationary logoed with images of belching factory smokestacks. Grey, not green, was the desired, apposite, politically-correct hue “back in the day.”

But even with the emergence of the first postwar generation that period was on the wane. Progress and change were altering the structure and face of manufacturing. Like agriculture, mining, and to some extent the fishery––the “extractive” industries––before the rise of manufacturing, the economy was shifting to what we now broadly refer to as the “service sector.” My generation that went to universities and many of those who before me went on the G.I. Bill, might have done their summer jobs at some factory, but they were studying for professions in the service sector. There were no courses in Punch Press 101 or a Seminar in Tool and Die Making.

The progression was all but an economic inevitability. Once primary or secondary economic activity provided the essentials of food, clothing and shelter to build a broad middle class consumption would become expanded to recreation, higher education, healthcare, and a host of other personal and professional services that have come to comprise the dominant and continually expanding occupational category since World War II. Employment network culture, mining and fishery has steadily fallen and employment in manufacturing has been stagnant for decades. Glassy office buildings have replaced those gritty factories in the centers of cities.

Kodak’s chapter in the story of American industrialization and its decline has its own characteristics. Its long-half enjoyment of near-monopolistic position in its industry may have contributed to his complacency over the digital revolution in imaging (although it owns some of the earliest patents on the process it neglected to develop commercially) and perhaps even the coddling of its employees to ward off any unionization might have contributed to that complacency. The chemical-based process, supplanted by silicon, may well go the way of the vinyl record, retained only by a faithful cohort devoted to its special qualities and even its nostalgic appeal.

But for a town that grew up on this industry that chemistry is in our marrow, retained in the memories of its distinctive aromas, university endowments and scholarships, the factories nestled into residential neighborhoods, and the streets in place names.

1946 my 1st year at school. I began in the 1st grade, my mother having held me out of kindergarten for some strange reason (hence my finger paintings never been very good). I think she wanted John (a year younger) and I to walk to school together., that way she could take a job, at Kodak. Since we came home for lunch I could make lunch for John and myself. At least that’s how I remember it. I don’t remember having a latchkey; I think she just left the back door unlocked. But that was, ahem, back in the day.

My mom, “Bee,” from the Kodak assembly line to wearing a chic executive assistant suit. 1973

My brother and several of my friends and schoolmates often had summer jobs at Kodak. I never did, so my only connection with the company was with the sports teams that were organized sponsored and run by the Kodak Park Athletic Association. Kids organized their teams in their local neighborhoods, chose or were given names by the KPAA, and were superintended by the same company that very likely employed one or more members of your family.

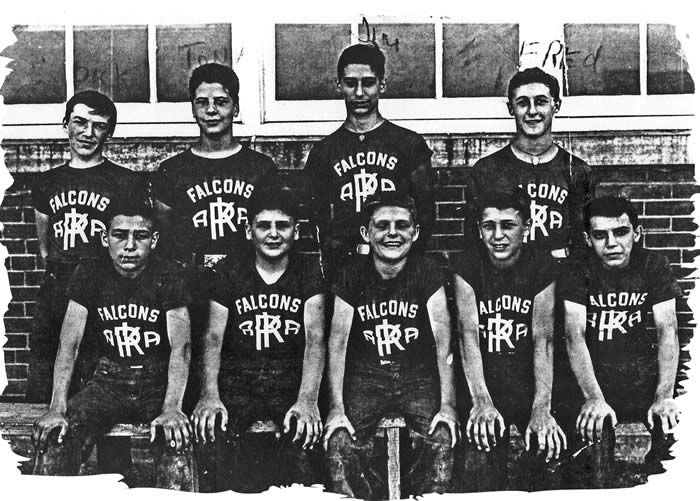

KPAA Madison Street Falcons fast pitch softball team, circa 1952-3. Author, back row 2nd from right. Brother John, front, 2nd from right.. I think we won our division.

My mother worked at Eastman Kodak until age 60. She started out on the assembly-line, putting together Brownie cameras, those little windup box cameras made for the masses and with which people took their first snap-shots and sent their film in to the company to he developed. Eastman Kodak, which had been founded by George Eastman in 1880, was synonymous cameras, photographic film, and photography in general.

My mother was one of more than 60,000 Kodak employees at its peak. She almost wasn’t. She didn’t tell me the story until years later, after her retirement, but when she first went to be interviewed for the job on the assembly line, as she related it, she was asked about her name. The interviewer asked her for her maiden name. When she replied honestly that it was Brunette Bianchi he told her that it was fortunate that her married name did not “sound Italian.”* Presumably, she might not have gotten the job, although her red hair might have mitigated the circumstances of her birth.** Nevertheless, “Bee,” as she was called, prospered at the company, working her way up to an executive assistant status before she retired.

Great swaths of Kodak’s plant footprint in Rochester have already been cleared. But fortunately, owing to the growth in other forms of employment as noted above, the city has actually had a net positive increase in overall employment during the period in which Kodak’s employment has dropped to nearly one-ninth of its all-time high. The city’s economic resilience––it started out as a mill town––doubtless owes something to the quality of the local educational infrastructure, something it would do well for political conservatives who mistakenly push for fiscal austerity. But that is a matter we will take up in these pages ahead.

____________________________________________________________

© 2012, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.6.2012)

*A question that has been annoyingly put to me more times than I care to recount.

**Kodak, although often spoken with an almost religious reverence in Rochester, was not without its failings. In particular, during the 1960s it was faulted for its failure to address the concerns of the racial minority community in the city. Saul Alinsky, radical community organizer, and the name that has been unearthed for blatant political purposes by the repugnant Republican would be nominee, Newt Gingrich, led a local social rebellion that forced the company to wake up even after some ugly incidents of social unrest in the city’s minority neighborhoods.