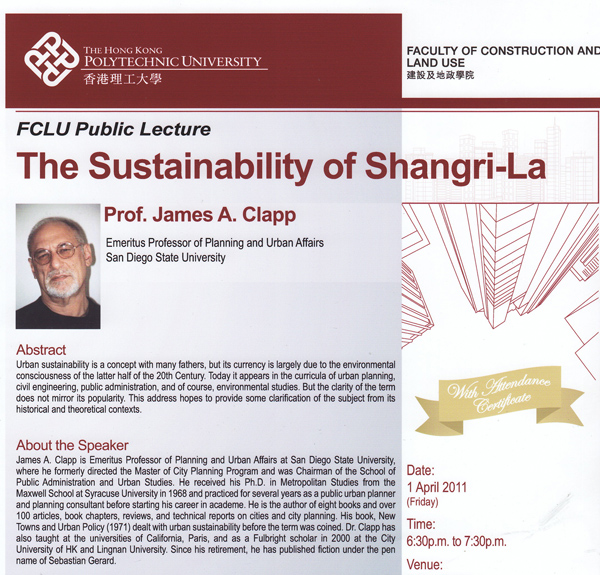

Earlier this year I was invited to give a public lecture at the Department of Construction and Environment of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The topic they wanted to hear was something on “urban sustainability,” a subject I should know something about although it has gone connotatively viral since I first hear it over a decade ago. The following postings are not my address as I gave it just from notes, but wraps together the points and ideas in those notes, while adding and embellishing a little. The title I gave the address is The Sustainability of Shanjgri-La. Given my audience I suspect that they were expecting a technological lecture, but I felt that they might need, and even appreciate, a lecture on the very term they seemed to be taking as well-understood.

The sustain pedal on my piano holds a note or chord that I play. The key verb here is hold (tenere, L. to hold, the etymological root of sustain). Sustainability, the term de jour in the parlance of environmentalism, but also now widely evoked in advertising and promotional media for even for carbon-based energy suppliers like oil companies. Like many terms in a media saturated world that feeds voraciously on novelty, sustainability runs the risk of becoming another linguistic cliché, one that it will become savvy to avoid, or to express with irony.

The sustain pedal on my piano holds a note or chord that I play. The key verb here is hold (tenere, L. to hold, the etymological root of sustain). Sustainability, the term de jour in the parlance of environmentalism, but also now widely evoked in advertising and promotional media for even for carbon-based energy suppliers like oil companies. Like many terms in a media saturated world that feeds voraciously on novelty, sustainability runs the risk of becoming another linguistic cliché, one that it will become savvy to avoid, or to express with irony.

For the present sustainability remains a “good.” Its association with the avoidance of waste, environmental degradation, global warming, and ancillary circumstances, gives sustainability’s attachment to an argument an axiomatic positive boost the equivalent of “organic” and “natural.” Nobody, of course (excepting some politicians I won’t name here) would want to sustain poverty, illness, pain, war and crime; we want to act to change these circumstances, not sustain them.

Yet, in the complexity of life and urbanism sometimes the circumstances and conditions we want to change are more than subtly related to or derivatives of the tings we want to sustain. The huge oil company I saw use sustainability in a puff piece on television is firstly interested in sustaining profits and market share, and if saying they are pursuing alternative forms of energy is useful to that end, well then nobody has a copyright on the term.

At another level is the question whether sustainability is sustainable. Heraclitus, wherever he is, must smile when he hears the word. He, you will recall, maintained that ”all things change, nothing remains the same” (panta rei kai ouden menai) Change is constant and inevitable, and although planning to guide urban change is not without some effect on its direction, the inevitability of change is transcendent. Change is built into, or anticipated, by the very economic systems on which they are constructed, of whatever form. Much of the very population growth of cities is a consequence of the migration from rural areas often incapable of sustaining life at more or less of the subsistence level. Indeed, a city that has long remained little changes is often* one that is economically depressed.

Another big question is posed by Darwin, whose notion of “natural selection” is change, or become extinct, is consonant with Heraclitus. So, where does the implied immutability of sustainability butt heads with Darwin? And when are we able to recognize changes (e-books, for example) that are highly adaptable and accepted system changes. The roadside of technology is littered with versions that natural selection gave a shot, but did not succeed (8-track tape?).

The third major intellectual challenge astrophysics. The Big Bang theory may posit a dynamic equilibrium that is beyond our ken in time and dimension, but it is contrary to any notion of stasis. Like it or not, all that we were, are, and will be are destined for oblivion.

Then there is the inevitable question of what should guide the changes that will inevitably pose choices of sustainability. This is the normative dimension of the matter that is intimately connected to where that guidance should come from. What is a good “steady state” or a condition in which change would be welcomed, is not always (maybe never) easy to evaluate. We cannot always see the normative implications in the early stages of change. When petroleum replaced whale oil it saved the lives of a lot of whales, who got to wait around until fossil fuels produced enough climate change to threaten the existence of whales in other ways. Meanwhile, some of us sit around writing of the dangers of petro-dependency on computers made partly of those same chemicals. Small wonder that oil companies are able to wedge themselves into a putative support of the idea of sustainability.

Finally, there is the matter of the appropriate auspices for guidance of change and maintenance of sustainability—planners and progressives (the government), or the sacred market—government, or (ahem) “enlightened and socially-conscious” private enterprise. Should people be allowed to vote on questions of sustainability with their plebiscites or with their dollar votes? There is, of course, the concern that either auspices would make choices that are consonant with the public interest, or increased productivity and profit. Indeed, with today’s “bought and paid for” elected officials, there might be no difference. As it is with many ideological disputes, the issue becomes who gets linguistic hegemony of the term sustainability, who gets to appropriate the language itself (“pro-life” for example).

The reader might think that I am leaning too Jesuitical with this, questioning the argument by questioning the very terms of its composition. But it seems necessary to do that, because, like many terms, sustainability risks becoming a term that by meaning anything and everything, means nothing. But perhaps its utility is in its very tendency to ambiguity and meaningless. Perhaps, in the process of debating its meaning we can learn more about the substance of it. So, if we are talking about urban sustainability, we have to look at the urbanization process itself. Is urbanization a process that tends toward some sort of static equilibrium, or is it, at its core, a process of dynamic dis-equilibrium? So, eventually we find ourselves in the domains of urban theory and urban history. That is next.

Meanwhile, even the sustained notes in my piano will fade out.

____________________________________________________________

© 2011, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 6.22.2011)

*There are exceptions: Brugge, Assisi, and many similar cities that make their living by resisting change to their historical atmosphere and architecture.