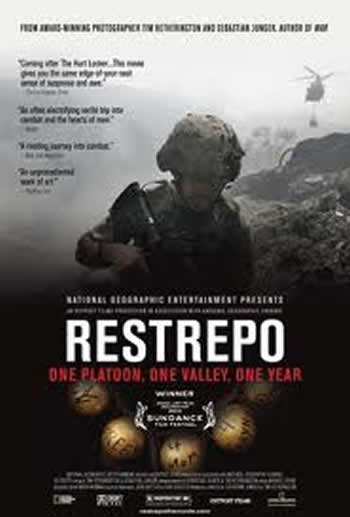

Veteran journalist Sebastian Junger and videographer Tim Hetherington spent an embedded year with an American combat unit posted to a remote hilltop—eventually named “Restrepo” for its fallen medic—in the Korangal Valley of Afghanistan. They “do not editorialize,” just report, but how you do that when you spend another year “editing” the documentary is delusional. Where, when, and at what you point a camera is, deny it if you will, a P.O.V.

Veteran journalist Sebastian Junger and videographer Tim Hetherington spent an embedded year with an American combat unit posted to a remote hilltop—eventually named “Restrepo” for its fallen medic—in the Korangal Valley of Afghanistan. They “do not editorialize,” just report, but how you do that when you spend another year “editing” the documentary is delusional. Where, when, and at what you point a camera is, deny it if you will, a P.O.V.

This is verite documentary making in dangerous circumstances, with all the jerky hand-held, freeze frame and blurred focus shots one expects from pictures taken under fire. Yet, for all the space, the effect is claustrophobic, tight, inside each soldier’s fear, or bravado. A lot of the footage, particularly that of the soldiers on their patrols, reminds one of news footage. What we see is not the American soldier’s P.O.V. but the filmmakers’ P.O.V. of the American soldier’s P.O.V, which seems to be a persistent scanning through rifle scopes of some distant and, for us, unseen enemy. The enemy is indeed never seen, alive or dead, unless he is represented as being among the local tribesmen who scrape a living as farmers or herdsmen from mean looking villages. For that matter, you never see an American casualty, despite the fact that the American base, and the title of the film are the name of the company’s slain medic, Juan ‘Doc’ Restrepo. We see the soldiers fires their weapons, during patrols, or from their positions on their base, but we never see their targets. In one scene, one of the soldiers is sniping at a Taliban somewhere in the unseen distance, and then casually comments on how he went down. In another scene of a patrol the Americans take enemy fire and one of them is wounded, but he is only referred to, not shown. It is as though this war is in some sense, like a video game; there is clearly something going on, but there is a remoteness from its consequences.

There is also clearly a remoteness from what the mission is about, and especially a seeming silliness about the intended combination of killing people and nation building. The alienation begins with the platoon being helicoptered in to a remote hilltop overlooking a valley of ambiguous strategic significance. As the edited in one-on-one with the camera sequences shot after the soldiers have been evacuated to Italy the remoteness and the unknowns engender strong bonding and camaraderie. They come off as still boyish young men, off on an adventure, earning their manhood in a time-honored fashion of growing up fast in combat. Even in reflection their collective impression of where they are going, and why, is “WTF?”

Their captain, Dan Kearney, gung-ho and soldier poster-boy perfect, is not really much more advanced than his troops. He calls the shots, literally and figuratively, sending men out on patrols, and holding weekly shuras with the locals. On the former it is not quite certain what they are supposed to achieve beyond killing some of the unseen enemy. Kearney’s professed objective seems to be to kill enough of them (Taliban) so they will leave the Americans alone to try to do –What? Open a Wal Mart? Although the Taliban are unseen, it is clear that it is their turf, their home and, since they have nowhere else to go, they are going to prevail or die trying.

What Afgans we do meet are at the shuras, where local men, in now familiar local garb, of indeterminate age, but with their ruddy complexions and missing teeth, are no strangers to the hard life of the mountains and valleys. And here we discern the distance. Kearney chews them out, swears at them, and comes off as an arrogant American asshole. It does not matter how much is lost in translation; his contemptuous attitude says it all. When one of the locals’ cows gets caught up in concertina wire (not seen) the troops kill and eat it (told but not seen), the tribal elders come to complain about it. They demand a payment for the cow of four or five hundred dollars, but are told they will receive rice and grain matching the weight of the animal. The Afghans lose ‘face’ and a cow and the Americans further worsen their chances of befriending these strange people. When they kill a few civilians and wound some children (unseen, although there might be some wounded kids lying about, hard to tell since nothing is explained) they show some faint remorse, but when they get to go home they claim they have done a good job. What that job was remains vague. When Kearney has a pep talk with his troops he rhetorically asks the question why are we there? There is silence until one of the men robotically says something about protecting our freedoms.

But there is always the sense that these guys just don’t belong there, and more so that they really don’t have much understanding as to why they are there. They don’t understand the language, or seem to understand the culture, but are like a gang who have set themselves up in some other gang’s neighborhood, and are now in some primitive rite of conquest-survival that is beyond their ken. It is as though the American military has composed a quirky group of guys bent on some adventure or without other options who become a mutual support group because they haven’t much of a clue about why they are where they are.

The psychology of all this is now getting familiar. The clearest dynamic is that the soldiers have nothing much to relate to other than one another. The form strong, foxhole, bonds, a “band of brothers” (or targets) and they hate people they hardly knew existed a few months ago for resenting their presence. They grieve when one of them is “KIA,” yet, in WWI 10,000 soldiers could be killed in the time of this documentary. There is a sense in which Restrepo seems like a gang war.

It is the interviews, conducted post-deployment, in Italy, that are most revealing. There is little, discussion of the role of America in Afghanistan, or much about the “mission.” These guys are happy to be out of there and seem somewhat traumatized by the experience. Specialist Cortez speaks of Restrepo’s loss and other dire incidents with the disturbing smile of someone who has been emotionally scrambled by it all. The all evince a lack of sophistication that is at odds with the responsibility for killing people. Indeed, it is not their responsibility. In this sense they might not be any different than soldiers fashioned into armies since the first. Mostly from the nether classes of society and from small towns and rural areas they are likely the same stock that Roman recruiters chose for their legions. They need to be able to respond to simple commands and simplistic rationalizations.

One gets the impression that as long as politicians and the people who profit from wars can manipulate guys like these, people like those who made Restrepo will always have new material.

____________________________________________________________

© 2011, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.31.2011)