Everybody loves a good story. A good beginning, a middle and, especially, a good ending. It doesn’t matter if its non-fiction, or fiction, so long as it has that nice narrative dramatic arc—beginning, middle and end. We tend to dislike things incomplete and unresolved.

Everybody loves a good story. A good beginning, a middle and, especially, a good ending. It doesn’t matter if its non-fiction, or fiction, so long as it has that nice narrative dramatic arc—beginning, middle and end. We tend to dislike things incomplete and unresolved.

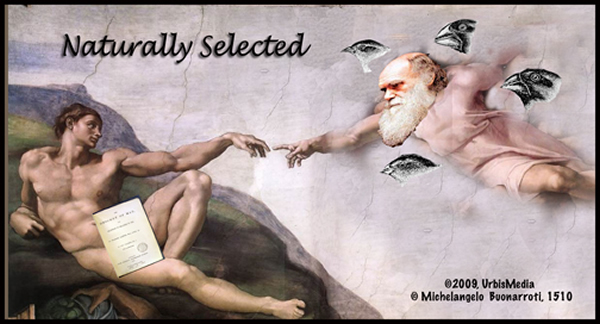

One of my favorite non-fiction stories is that of Charles Darwin and the voyage of the Beagle, the ship he sailed around the world on collecting the data and samples that led to his famous, and arguably the most world-changing discovery in history.* It is a non-fiction story with all of the dramatic elements that would make for a great fiction story. A young naturalist on a ship captained by a bible-thumping master. Exotic locals and creatures, a rivalry with another scientist on the ship, its what Indiana Jones should be. Then home, to Kew, and a great internal struggle with his faith and his wife about publishing his findings that appeared two decades later, in 1859, as Origin of Species. [full title On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.]

What is interesting to me is that, although Darwin’s personal story is a wonderful narrative, the story his masterwork of science tells of the descent of man, is not. It is a story without a timeline, without the arc of drama, and without a plot, destination, or great normative message. It has no moral, no good guys and bad guys, and its “story” is one that “evolves” over eons of time in such a way that our own relationship to it seems trivial, insignificant and beyond our ken.

Darwin’s Origin of Species is an account and explanation of how we came to be the humans weevolved to be. No wonder it would start a fire if you set it beside a copy of the Bible. You see, Darwin’s account of how we got here not only takes rather more time than a week but, even worse, it doesn’t have a plot. And that drives those of us who no only like a good story, but need a good story, and a story with a good ending, to anger and/or despondency.

In Darwin’s story we humans are one of a vast number of extant species on one small planet in a vast universe, and a fairly recent species at that. Darwin does not say we are created by a god, but by a process of “natural selection,” and he does not say that we are necessarily “progressing” to some “higher” more perfected form (indeed “descent of Man” seems rather prophetic), just adapting and surviving by that process and, he does not say—as does the Bible—that we humans are the central purpose of creation. It is the Bible that avers that we are. The Bible is a story about God’s special creation, us, who pissed him off with that Garden of Eden business, and how we try to find our way to is his special afterlife place, heaven, when he is finished with the earth. Beginning, middle, end.

Darwin, the great natural empiricist, collected all sort of specimens and evidence, made scientific deductions, found evidence in nature to support those (as have many scientific discoveries since that are consonant and confirming of the central Darwinian thesis). The Bible has not a single shred of verifiable evidence for the existence of God. History raises critical issues with it throughout with its people, places, and events. Amazingly, the biblical faithful will criticize the gaps in the fossil record of paleontology, but the historical mess that is the Bible seems not to raise a question mark.

This segues to another important pint of this essay. If one believes a story as prophesy, as a revealed truth about the future, then the narrative becomes a script(ure) for the future—not just they way things were, or are, but the way they are intended to be. To believe in any story as more than just a story can take us to a different place. The religious narrative is not the only dangerous one. There are those who believe in an historical narrative, one that assigns the United States a central position (role) as the leader (protagonist/hero) of the world’s march towards democracy (and one might add Christianity and Capitalism). For many Americans this imagined prophesy for America is a justification for an exceptional political-messianic role in global history. Some see the historical trajectory of this role involving even cathartic phases, even Armageddon-like events.

One can begin to appreciate the implications of the Darwin thesis. To accept that thesis is to step outside of religion’s story, and outside of fantastic historical narratives. One can begin to understand the pressures that kept Darwin from publishing his discoveries for two decades. He had battled with Captain Fitzroy on the Beagle (Fitz later committed suicide), with his wife and local pastor, and with his own conscience. His own society was suffused with Christianity and his culture with the Empire that saw its god-given historical role to bring (its) civilization (and fish and chips) to the world. To step outside that narrative risked being adrift in a different story, without a “beginning and end,” if there is either, or they are not the same, and a “middle” replete with a brutal process of adaption and extinction. Scary.

Stories are the way we humans have carried our species narrative from one generation to the next. Many of those stories are great, insightful, and carry great truths with them. Who would gainsay Homer, Shakespeare, Melville, or Sebastian Gerard in this regard. So how could they be dangerous? Well, fact and fiction are sometimes like a toggle switch where facts influence and inform the way we make up stories, and sometimes stories influence the way we percieve the factual reality of the world. The danger is when we take the fiction as fact. We often do that because the fictional narrative asks us, like a movie, to (temporarily) suspend disbelief and just enjoy the story. When we don’t return to reality, but to prophesy, trouble often follows.

Facts can be unentertaining and complicated. But while global warming or dreaded diseases can be undone with the wave of a pen (or a joy stick,** the reality of solving those problems requires a more involved, attenuated process, and a different cognitive faculty. No substitution of fantasy for the facts will make perception into reality. When the religious narrative, ideologically-corrupted history, or other fictions become our reality then God (ooops) help us (all he needs is six days). Mr. Darwin will take a bit longer; but I am counting on him.

It would seem that humankind would learn something from history and the progress of science, but here we are, in the 21st Century having the same old battle between faith and reason. Perhaps we do not learn much of anything over time because each new generation has to make its own accommodation between these dualities. But Mr. Darwin says that we do, in fact, learn something—we “learn” to adapt, by natural selection in recondite ways, not as individuals but as a species, to a world that is increasingly of our own creation.

The Italians have a proverb: Se non è vero, è ben trovato.” (“[Even] If it’s not true, it’s a good story.”) It’s just important to be able to k now the difference.

____________________________________________________________

© 2010, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.4.2010)

*Although there are Darwin’s own account and letters, I enjoyed Alan Moorhead’s Darwin and the Beagle: Charles Darwin as Naturalist on the HMS Beagle Voyage(1970)

**Fantasy football is an interesting phenomenon. While the most “truthful” aspect of sport is that it is played out there in front of us, win or lose. There are players and there are spectators. But fantasy football adulterates that truth with the unreality of conflation of the spectator and player. It is as though the reality of actual football is not satisfying in its outcomes as some fanciful, adulterated, version. The religious narrative performs the same delusion.

[OK, I slipped in that thing about Sebastian Gerard. So sue me–after you buy the book.]