©2010, UrbisMedia

Recently, I unpacked an electronic device I ordered on line. It was beautifully and cleverly packaged, making the kinesthetics of the experience part of the thrill of possessing something new. It opened like some sacred ark of consumerism, revealing the device as though it were a jewel possessed of some mystical power. It did, of course, hold the power that comes with the possession of something new, and delivered to us with a presentation that titillates the thrill of expectation. It is pristine, new, virginal, a gizmo that you alone get to “deflower” when you push that power button. Along with that experience came an olfactory delight—the smell of the new.

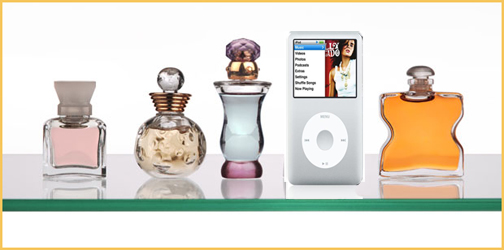

We all know that smell, the clean, electronic aroma of unpacking a new iPod, the crisp, fresh fragrance of some new clothing fresh off the rack and, of course, that ineluctable delicious scent called “new car.” With apologies to Robert Hughes, whose art history, The Shock of the New, I read some years ago, I am proposing that there is something far more prosaic, but also a significant aspect of our culture, the addiction to The Smell of the New.

What I am referring to, more specifically is familiar to us in the term shopping. For most of human experience we didn’t shop. There was no such verb because we spent out time hunting and gathering. That is not to say that a whiff of a herd of bison, or the sweet bouquet of ripened fruit on a vine or tree, did not have an effect similar to opening that box with a pristine MacBook Pro in it. But we are a long way from those days. Today, shopping—the very experience of trying on several new pairs of shoes or dresses and sport jackets, of leisurely walking trough auto showrooms, having a day at the mall amongst all the fresh new consumer products that were last touched by an assembly worker in Dongguan or a Nike employee in Indonesia —is an activity that is more and more generated not by need, but by want.

This is because capitalism and economic growth require it. We must be willing participants in the process of obsolescence that keeps the engine of consumer demand humming along. Even the tragic day of 911 should not keep us from shopping, George Bush pep-talked us before the dust had even settled. We would show those terrorists we were ready to take them on, outfitted with new jeans, running shoes and the latest Blackberry—the fashion statement turned into geopolitical threat.

I know people who used to buy a new car every year. It was like a sacred ritual so they could breathe in that “new car” smell. Of course the fashion “industry” changes the fashion every year so that we are made to feel that we are not “with it”* and current with our presentation of self. Capitalism is perverse in changing products, adding new styles and features, anything to make us want that experience of something new, the latest thing. Businesses are like crotch-sniffing dogs, profiling, focus-grouping, and targeting us into consumer niches, making us obsessed with having something new. In consequence, we all have more stuff we need. We have stuff that we purchased for reasons we have long forgotten, and the thrill of the possession and the smell of the new are long gone.

I know a lovely woman (Oh, Jesus, I’m gonna pay for this!) who regularly went out to a clothing store and purchased as many as a half-dozen dresses and other items. She would return home, try them on, see how they looked with different accessories and such, and then return some, or all of them. It was not that she needed new clothes because she had a fine wardrobe. I surmised that is was the experience of shopping, of the possibility that there would be the thrill, momentary though it might be, of the smell of the new. Shopping has become for many people a form of diversion and recreation. It is sort of a hunt, for the bargain, the surprise item that jumps out at you and says, “you really don’t need me because, until this moment, you never even knew I existed, but now you can live without me.” You buy it, and the gods of capital smile. Soon the thrill dissipates, a place is found for the object of induced desire finds a place in a closet, and then eventually, the garage sale or hand off to AmVets, to make space for something new. Later, someone might show up with it at Antiques Roadshow, or Pawn Stars, and ironically its oldness will be its charm and value.

One wonders whether that perfume of negative ions that rushes out of the box of a new computer or iPad, or that stew of sealants and Corinthian leather that is the first whiff when we crack the door of a new Beemer or Benz are concocted by some wizard of olfaction like that guy in Patrick Susskind’s Perfume. Are those irresistible scents just a by-product of packaging or manufacturing, or are they bouquets that have been tested in some secret laboratories that drive mice and monkeys into sexual frenzies? Do those chemicals create some synaptic interchange that makes us get up out of that chair, grab our credit cards and get out there and compulsively and unwittingly shop for that smell.

What makes me (confession time) click n my computer bookmark for Amazon.com and open up my “wish list.” If he existed, God would know that I have enough books to keep me reading for the rest of my life. But no, I will “shop,” looking at new titles, succumbing to the reader profile that Amazon has assembled such that they almost know what I want before I know it. But I know what my anticipation is; not only the arrival of another book, but the smell of it—a new book that smells good enough to bite, or a old, used book and has the antique aroma of deteriorating paper (the “new” need not be something new, it is our acquisition and possession of something that is the experience of the new) and sends me into imagining who else might have read it. I’m hooked, I know it, and with a nose like mine there isn’t much hope.

____________________________________________________________

© 2010, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.26.2010)

* See Babo Archives, 22. 8: The Culture of Inadequacy 7.30.2005