The more reserved Hiberianized Roman Catholics used to be shocked at the sight of an Italian RC (almost always a woman) conversing with a religious statue (usually, but not always of the BVM) on some side altar in church. It smacked of idolatry, a residue of those pre-Christian Roman days of temples for all sorts of imported deities from Greece and Egypt, and of home shrines for tutelary gods available for convenient verbal supplication. Italic peoples liked their gods up “close and personal” and lending an ear to their devotees.

Talking to statues and idols goes way back, and is not uncommon in many societies. But statues talking to people is a rarer occurrence. Rome has several taking statues dating back to the Middle Ages when the city was ruled by some nasty Pope-Kings. The lore about the talking statues includes the hypothesis that such statues spoke on behalf of the common people, especially when the politics was such that a loquacious person might end up as a test dummy for Inquisition torture implements for offending a powerful pope. Better a statue “utter” seditions and maledictions.

Pasquino today, still with something to say

In a little piazza nearby the renowned Piazza Navona stands a visually unremarkable statue from antiquity. All that left of the statue of “Menelaus with the Body of Patroclus” is a torso and badly damaged head. But its fame owes not its lack of beauty, size or completeness, but its renown as Rome’s most famous “talking statue,” called Pasquino. Now Rome’s talking statues do not actually speak; they communicate by way of the more well known Roman predilection for wall writing, or as it has become known, graffiti .

Pasquino’s name actually has nothing to do with the real name of the statue, but is the name of a tailor who once has his shop nearby. Nevertheless the graffiti that used to appear on the walls beside him, or on the statue’s base, are often “attributed” to him. Who would haul a statute off to prison or the gallows? Many books have quoted Pasquino as if he were the real author of a stream of clever epigrams and puns that continue to be posted to it since it was unearthed in 1501.

When the Barbarini Pope Urban VIII plundered bronze from the Pantheon to make the columns for the main altar in St. Peter’s, Pasquino bore the pun: “Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barbarini”(what the barbarians didn’t do, the Barbarini did). Another time, he satirized Pope Innocent X’s sister-in-law, the less that holy Olimpia, with the cleaver play on her name: “Olim pia, nunc impia’ ”(Once pious, now impious).

So to be worthy of a attribution to Pasquino the anonymous author has to employ not simple invective, or insult, but had to compose a clever satire, pun or lampoon. Such remarks would then be worthy of being called a pasquinade.

Another Roman talking statue, called Babuino, resides right on the street that bears hiks name, Via Del Babuino, not far from the Spanish Steps. Babuino’s head comes from some other statue, but is sufficiently unhandsome to live up to its name, The Baboon.

One of Babuino’s cleverest pasquinades was composed to strike a punnish blow with the name of Napoleon Bonaparte when the French were plundering Rome, and The Baboon declared, rhetorically in Italian this time : “I Francesi son tutti ladri? Non tutti–ma buona parte.” (Are all the French thieves? Not all, but most of them).

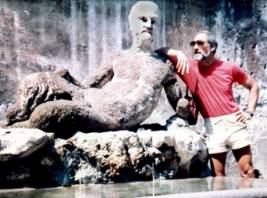

Babuino , the Baboon, with friend. (The Baboon is on the left)

Among the other ther talking statues were called Il Facchino (the porter), Marfario, a reclining statue of a river god that one pope stuck in a museum to shut him up, and Madame Lucrezia, who was actually the large bust of a priestess of Isis. But these days most of the sayings of Rome’s talking statues seem to lack the cleverness of those of old. Recently, Babuino had one saying commenting on Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi: “ porco ladro” (pig thief). Accuracy is a necessary, but not sufficient, element to qualify as apasquinade.

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.29.2004)