© 2009, UrbisMedia

I have made much in these pages of the claim that religious belief is based on nothing but a need to fill in the unknowns of life with something, a narrative, a reason, a meaning. The fear of the unknown inclines us to accept “plausible” narratives that are, shall we say, comforting. The most comforting element is that this life is not the end of life, that Jesus, or some other prophet has come to tell us that there is some sort of “eternal life” awaiting us; if we just abide by some rules and behaviors and we will be with our loved ones again in some golden city, or picnicking with virgins alongside rivers of Cabernet Sauvignon (rouge, ou blanc?).

I don’t completely dispute this notion. But eternal life might not be anything like we have been told or have imagined in our rather fairytale ways. Maybe there is some other dimension into which our consciousness goes, but it is something well beyond what we have imagined. “Intelligent design” advocates are always making the case that the universe is such a complex phenomenon that it could not have come into being without some sort of higher intelligence involved. They expect that you will substitute their notions of God for that “intelligence,” and fill in the biblical narrative for its motivation. Their premise is complexity, bit their conclusion is pure simplemindedness. They want us to stay stupid because that’s how they get away with selling their nonsense.

Here I want to make two related points about this scenario. One is sort of positive; the other negative. First is that there may be some need that we humans have to create the illusion that there is a scenario, a narrative to our existence. People will tell you that they could not abide atheism because they would find it too depressing to go about thinking “this life is all there is.” When we are little children we might create imaginary friends to fill in loneliness in our lives, or to have “someone who completely loves and understands us.” Later, maybe Jesus or some other deity, or a saint steps into that role. Even in a purely secular sense we do this. We go to the movies and willingly “suspend” our disbelief so that we can identify with a protagonist and let our feelings get into the story. Little vacations from the reality of our lives can be part of the comfort we need to deal with the hard parts. Moreover, sometimes that imaginary part is very fantastic and supernatural. Fantasy makes up a large part of our movies, television and video games. Throw in pornography and the proportion really jumps up. So it isn’t too much of a cognitive leap to, or from, religion.

I have not thought about my own willing suspensions for some time. I remember that, as a kid, I had a little rubber Indian that brandished a tomahawk, who was a “friend” I invested with a personality. I also used to imagine myself as a tiny person who lived in a Christmas tree ornament and could travel about among the branches and lights. I always seemed to imagine myself as a very small creature, never a giant hero. I think I, unknowingly, preferred to be the observer, and would not have liked the loss of privacy in being a giant. Soon I was reading books and listening to the radio, and my imagination proved to be my favorite human faculty. But my imagination never really latched on to biblical narratives; I never imagined myself hanging out with the “Galilee Kid” and his gang of Twelve. And I didn’t identify with any of the saints, many of whom, even then, I thought were whack jobs. Frankly, religion’s fantasyland struck me as rather third-rate.

But I am digressing into my reverie. The second point I want to make is that this need for a narrative, comforting though it may be, is somewhat delusional. It puts us—we humans, “made in the image of God,” as we like allege—at the center of the whole of creation. Here we humans sit, our period of existence a veritable nanosecond of the periodicity of the universe, thinking that we are the reason for it all. No wonder that the Creationists want to compress the period of creation to six-thousand years—then everything begins with us. How convenient.

I admit that we are pretty amazing concoctions of carbon atoms, that the earth as a place to live, beats the hell out of Jupiter or Mars, and that we are damned clever at shaping our world to our needs and desires. The story of our “six-thousand years” itself is fascinating, wonderful (and horrible), even the part religion plays in it. But we are also in denial that we just might not be the center of the universe and the motive for its creation.

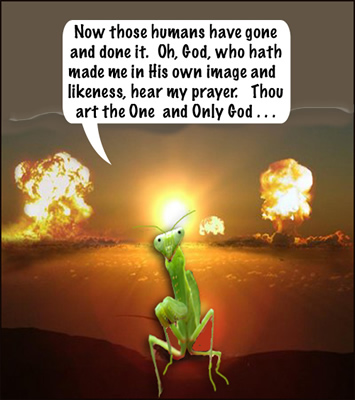

Are we? Look at the universe from the “intelligent designer” premise again. We could be an “accident” of life-conducive conditions that permuted from possibilities of billions of stars and other galaxies. It’s just as good a hypothesis as God sitting somewhere figuring out how to put the legs on a preying mantis before he has to rest on Sunday. If we regard ourselves as a particular, and exceptional, expression of creation we might just be in for a big surprise. God could look like ET, and not Johnny Depp. If there is all that evident complexity and its concomitant possibility in the universe, how is it that we believe, with such certainty, that the narrative we have from the Bible, that its story of creation (which we know enough already does not hold up to the evidence), that the “new covenant” offers certain “eternal life” and that—rollicking to that big final scene with all the explosions, Jews converting to Christianity, Armageddon, and that stuff—the Book of Revelations is how it is all going to play out to some Rapturous conclusion. Wow, what a movie!

But people believe this stuff, with certainty. Not all religions, but the Western Christian modality, involve a narrative with a beginning, a middle, and an end. At some point in the future—and some people believe it is imminent in their lifetimes—the earth will no longer be (as they believe it was never meant to be) our abode. At some point, like so bad Rambo movie it will conclude with that explosive ending.

Does this mean that we are, or something is, supposed to ruin the planet. That’s the narrative for the Rapture types, the believers in the Book of Revelation. The Revelationists have a ready answer—when the Armageddon comes—it will because “it is written,” because it is the fulfillment of prophecy. The two candidate endings—thermonuclear annihilation, or ecological disaster—are just awaiting one trigger or the other. Why care about world peace or environmental integrity when the final act of the Biblical play calls for a fiery finish. Sorry, but I have a problem with that scenario, however comforting it might be to the simpleminded. It turns the earth into a “means to an end,” something that is not really a part of us, but apart from us—something to be used, and used up, not respected and husbanded (biblical term), but to be subdued by the multitudes. I don’t like the Biblical script very much.

Someday everything and everyone we know will be dead and gone. The earth will likely, at some point plunge into the sun and become, again, part of a cycle of creation/destruction that doesn’t give much of a damn for what our biblical prophets conjured. Although by then the earth might not be habitable anyway. Meantime, religions, as some do, might want to find a good reason for taking better care of this creation. Although religions have not had much use for science, and even seen it as the enemy of faith, it is science that is telling us just how fragile this “complex” of variables actually is.

Disrespect for the earth’s ecosystems, often with the “blessing” of religion, is a problem that may be reaching—if it has not already reached—disastrous irreversible proportions. Greenhouse effects have already raised average temperatures one percent, a variable that has shown to result in snow and ice melt and permafrost damage in excess previous predictions. With less reflective snow the process becomes compounded and cumulative. The major religions are tied into economic systems—indeed benefit from them—that are far more a part of the problem than the solution. Ignorance of, and a combative attitude by, religion toward science only give more support to the notion that global warming and its concomitant problems are “debatable” or simply cyclical.*

Nuclear proliferation, the other sword of Armageddon continues, with more and more of states that have religious regimes or religious grievances with other faiths, leading the way in terms of acquisition and threat. Muslim Pakistan, Hindu India, Jewish Israel, have joined the Christian good ole US of A with the capacity to ignite and/or conduct a worldwide nuclear holocaust.

It appears that we have managed to set up the Biblical narrative of both willing suspension and self-fulfilling prophecy. How comforting.

____________________________________________________________

© 2009, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.2.2009)

*See Bill McKibben, Think Again: Climate Change, Foreign Policy, Jan/Feb 2009