By way of some curious synaptic connection when, I first picked up this book, I had a reverie of a personal experience in the Chinese city of Xian many several years ago. “Are you going to the Barbeque Fashion Show this evening?” the desk porter at my hotel had asked me. There was also a poster for the event in the elevator, indicating that it would take place on the hotel roof, and that the “all you can eat” price was very reasonable. It sounded like a good idea, and at six o’clock I was up there, interested far more in filling my stomach than in a “fashion show.”

By way of some curious synaptic connection when, I first picked up this book, I had a reverie of a personal experience in the Chinese city of Xian many several years ago. “Are you going to the Barbeque Fashion Show this evening?” the desk porter at my hotel had asked me. There was also a poster for the event in the elevator, indicating that it would take place on the hotel roof, and that the “all you can eat” price was very reasonable. It sounded like a good idea, and at six o’clock I was up there, interested far more in filling my stomach than in a “fashion show.”

The barbeque was good, and the fashion show turned out to be—explaining why it was almost exclusively “businessmen” at the event—a show of lingerie. The announcer explained as each lovely, young Chinese girl passed among us in the steamy evening air of Xian, and with an exaggerated fashion runaway “walk,” what a wonderful idea it would be to “take such sexylingerie home to your wife.” One after another young beauty paraded her wares among us. But the effect of the food and drink was soporific on me and I got up and left before it was over.

As it turned out, the organizer of the event was in the hallway, in which several of the lovely models awaited their turn alongside racks of lingerie. He stopped me and asked if I had seen anything I liked. I said I wasn’t interested in purchasing any and that I was tired and was heading off to my room. Well, then, he said, “We can arrange a private show for you in your room.” I declined, but it wasn’t until I was in the elevator that it hit me that I had just attended a thinly-disguised parade of very pretty hookers masquerading as a fashion show. It wasn’t to be the first time that things wouldn’t be quite what they seem to be in China, a placed where even the language can be read to have very different meanings.

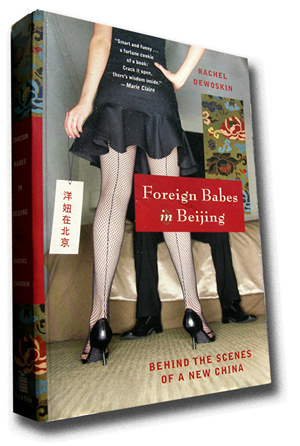

That’s what I like about Yang Niu Zai Beijing—it is one of those books by a zhongguotong (China hand) that revels in the nuance of China and its language. For example, DeWoskin notes that the title—more about that in a moment—is Yang Niu, not Yang Nu. The latter would be “Foreign Girls,” but Niu is a girl who is a “babe.” A slight change in sound with a lot of difference in meaning.

The title is from a Chinese television soap opera that DeWoskin was recruited for quite by accident. But the producers felt that she fit the part of an American babe who seduces a handsome Chinese guy away from his virtuous Chinese wife. So Foreign Babes in Beijing is the title of this series of “feel good” TV for the Chinese: the main guy gets a chance to kick the ass of a Western guy (to counter the notion of Chinese guys as wimpy and effeminate), and DeWoskin, covered in make-up, jewelry and big hair, is Jiexi (Jesse), the American femme fatale, who gets to do semi-nude sex scenes that contrast with the image of traditional, chaste Chinese women.

DeWoskin, the daughter of an American sinologist professor who took her on trips to China when she was a child, is a Columbia graduate who returned therefore five years to do public relations work for American corporations jumping in on the Chinese economic boom of the 1990s. She came to the Jeixi role by happenstance and with only some school acting as experience but, after the release of the Foreign Babes show, became a celebrity in China. The irony was that she received only eighty dollars an episode while the show was immensely lucrative for the producers.

There is nothing in Foreign Babes of the steamy tell-all about sexually-liberated Chinese that has come out in some books from Chinese authors in Shanghai in recent years. DeWoskin even demurely deals with the description of the “nude” scene she has to do with the male lead. While she is in actuality sort of a “foreign babe” in her personal life, having had some Chinesenanpengyou (boyfriends), and frequenting the clubs and hot spots of Beijing that the Western tourist doesn’t even know exist and, most significantly, getting to appreciate the culture of Beijing and China from the vantage that fluency in Mandarin affords. Despite her main job a in public relations (she pints out that PR (piyar) means, means “asshole” in Mandarin), she moved in the pop culture and bohemian circles that were burgeoning at the time. Among her friends were emerging artists such a Zhou Wen, and Chinese rock star Cui Jian, and budding filmmakers.

Even though it concentrates on Beijing in a specific period, Foreign Babes is one of the best insights into the expat life in China that I have read. De Woskin is smart, but, even being a “China lover,” (see review of China Lover, last month) is balanced and respectful, and in many respects remains awed by the complexity of the culture. At several points in the book she repeats an observation that make in my own travel memoir, The Stranger is Me, that she feels much more American when she is in China. Her opinions and observations are sharp, measured and insightful. She provides informative explanations of how Chinese view television narratives differently than we do (125), and what is called “sideways negotiating” (141), both learned “on the job,” as well as the dynamic of change in the city itself. She seems to relish the mistakes and missteps she makes even more that the linguistic and cultural differences that make us laugh. I did when she pointed out seeing a sports jersey celebrating Michael Jordan that read “Chicago Balls.”

Perhaps most interesting were the few pages at the end which are devoted to the events of May 1999, when the U.S. (or NATO) bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, supposedly by accident. DeWoskin and her expat friends were deeply affected by the outrage of the Chinese (and equally angry at the American government). But she puts together in a few pages the best, and fair-minded, explanation of the affair and its aftermath that I have read. She since has returned to New York for more academic work, in poetry and translation. But she plans returns to China for more experiences that provide a fresh angle on ourselves as well as a foreign culture.

That put me in mind of another of my own, if less interesting, China experiences some years ago when a sore back had me in need of a massage when I was at a hotel in Chongqing. I called the front desk to order a masseur or masseuse (to avoid giving offense I asked for whichever was available) to come to my room. Shortly thereafter I opened my door to a young woman in a warm-up suit who must have been no more than five fee in height and less than one hundred pounds. I remarked that she seemed rather xiao (little) for a masseuse, but she gave me a wry smile and motioned me toward the bed. With what must surely be the strongest tiny hands in all China she proceeded to nearly kill me for forty-five minutes. My own hands were trembling when I gave her a tip. But my back felt better. Or was it that everything else hurt now? That’s China.

____________________________________________________________

© 2009, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 1.17.2009)