There is a passage that alone is worth the price of this book, at least for me. Anyone who has read the pages of Dragon City Journal is aware of the contempt we have for evangelists—soulsnatchers, we call them. We are ecumenical about it; it doesn’t matter what faith they come from, we detest soulsnatchers of any religion.

There is a passage that alone is worth the price of this book, at least for me. Anyone who has read the pages of Dragon City Journal is aware of the contempt we have for evangelists—soulsnatchers, we call them. We are ecumenical about it; it doesn’t matter what faith they come from, we detest soulsnatchers of any religion.

The following is from page 22. It is about Nova Scotian Presbyterians George and Ellen Gordon, who landed in Erromango in the Vanuatu Islands (New Hebrides) in 1851. “They managed to convert [only] a handful of people in the course of a decade, but then they made a fatal error. When an epidemic of measles broke out and killed hundreds of Erromangans, the Gordons announced that Jehovah was punishing the islanders for remaining heathen. The couple were blamed for the epidemic, hacked down with axes, and eaten.”

I admit it, I got a big laugh out of this. Serves them right. I saw the admonishing hand of Jehovah guiding those axes into those arrogant skulls of those soulsnatchers. I have a fascination with cross-cultural encounters, but the permutation of crossed-cultures, crossed social-evolutionary periods, and crossed-cosmologies, is akin to what an encounter will be with an extraterrestrial. The Gordons learned to their regret that they had brought their god with them and it was they who were responsible for bringing his wrath down up the heathens.

Montgomery, a Canadian photographer and journalist followed in the wake if his great-grandfather, the Right Reverend Henry Hutchinson Montgomery in search of some answers not about the Gordons, but another Protestant missionary martyr, John Coleridge Patteson, whose skull was split open by the natives of a Nukapu, a tiny atoll in Melanesia, where he was the first Bishop. Montgomery was also in quest of his own beliefs and, what makes that endeavor such a fascinating journey is the mystery it creates as to whether he will find those beliefs in the faith of his ancestor, or in the ancestor spirit world of the primitive peoples of the Coral Sea.

Protestant Missionaries followed in the wakes of voyages of exploration and then whalers and were the advance troops of colonialism. Sent out by the London Missionary Society and other missionary organizations, zealous and courageous missionaries, often married couples, softened up the natives, bringing their monotheism that challenged the prevailing power structures and social systems. No doubt there were meetings that would rival Close Encounters of the Third Kind, at least for the natives. The smart thing to do from the native perspective would be to put these people into martyr status as quickly as possible. Little good could come from the encounter; the missionaries threatened their souls with their new god, and their bodies with their new diseases. Introducing a new religion caused, in many cases, schisms that resulted in civil wars and corrupted long established cultures.

By way of the writings of missionaries Montgomery’s travels among these peoples takes place in temporal parentheses that span well over a hundred years. But even today he finds some things unchanged. Among some tribes men still wore nothing more than he nambas, the penis sheath that is held erect with a cord tied around a man’s waist. There was still the deep fear of the spiritual dangers of being near a menstruating woman. And there was that lingering matter of the “taking of heads.”

Montgomery was a descendant of the new religion, but there were elements of atavistic and primal faiths that clearly attracted him. He admits, “I had always traced the impulses of faith to environment. In the years after I abandoned my family’s church, I found that the universe spoke to me most loudly in the fullness of mountains, the endlessness of the sea, the fury of storms, the boom and crack of living physics . . . that’s when the world itself seemed to offer a voice and a breath that felt something mana [sort of a grace], and which begged to be given a name and a shape and myth to explain it all.” (70)

Those who preceded the author had already found their faith. Conflating Christianity with “civilization,” they were not only bringing the natives the right god, they were bringing them the right way to live. The natives had their own ways of doing things, called kastom, that included long-practiced traditions, folkways and beliefs related to ghosts, myths and magic. Anglicans tried to incorporate kastom into Christian ways, whereas the Presbyterians saw them as “pagan.”

The Christians also brought death. The natives had no immunity to pneumonia and influenzas that were part of the cargo of their ships. What added to the destructiveness of these diseases was that the natives “tended to give up and wait to die rather than fight their illnesses.” They behaved similarly when they believed that they were the victims of black magic. Even when the missionaries admitted that they were the cause of plagues that devastated the populations of these islands some of them seemed more concerned that they send the natives to their graves “as Christians.” What chaos and destruction they didn’t bring with their Bibles and diseases, Christians also brought with their introduction of guns to these islands.

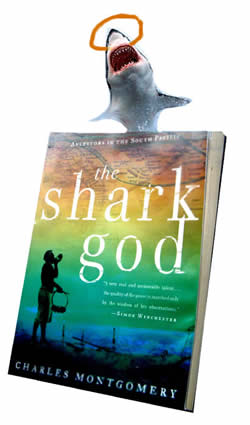

Montgormery’s account of his travels and encounters with the naives of these islands is part travelogue, part journalism, part anthropology (and commentary on formal anthropology). But it also turns mystically murky at points. This is most noticeable in his account of the Shark God, where, on the island of Honiara, he seems to encounter the holy beast while observing the dive of guide who he calls “the shark boss” in the lagoon. The dive takes place at night and, as the shark boss sits cross-legged on the floor of he lagoon, he recounts, “[b]etween the halo of his flashlight and the impenetrable void, in the grey murk between certainty and imagination, I saw something like a great drifting shadow. It was sleek, as along as a car and as black as cooking charcoal.” In recollecting it later it becomes more certain to him that what he saw was a huge shark circling “around my friend the shark boss.” Now, “the story became whole, and I grew more certain every time I repeated it. Now there is no doubt. Yes, it was a shark. Yes, it was Bolai. Yes, an ancestor could be summoned from the darkness. I would believe and it would be true because I believed. . . . Myth, like love, is a decision. What it answers is longing. What it demands is faith. What it opens is possibility.” (294)

My reading of this is that this is where the author both experiences and explains that religion—of whatever sort—is a decision to set aside a concern for rational explanation for the need to believe. In the religious imagination anything is possible, even that God is a shark.

____________________________________________________________

© 2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.8.2008)