When actor Richard Gere suggested at a gathering in Central Park on behalf of the policemen and firemen who had worked the World Trade Center attack that America perhaps should find out what grievances Muslims might have against America he was booed off. It was perhaps not the time for such a suggestion, American’s having just seen Palestinians dancing in the streets at the crumbling of the towers. Many, probably most, Americans are still disinclined to ask themselves that question, a silent answer that is indicative of both our ignorance of and arrogance toward other nations. Many still believe that the terrorists were Iraqis, not extreme Wahabbist Muslim Saudis. The demonizing of Muslims in general worked better as a causas belliin a clumsy, misdirected military response that was going to inflict a lot of collateral damage and result in Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. One might still be painted a terrorist sympathizer or even a traitor to broach the notion of some American foreign policy culpability for what happened on 9-11.

When actor Richard Gere suggested at a gathering in Central Park on behalf of the policemen and firemen who had worked the World Trade Center attack that America perhaps should find out what grievances Muslims might have against America he was booed off. It was perhaps not the time for such a suggestion, American’s having just seen Palestinians dancing in the streets at the crumbling of the towers. Many, probably most, Americans are still disinclined to ask themselves that question, a silent answer that is indicative of both our ignorance of and arrogance toward other nations. Many still believe that the terrorists were Iraqis, not extreme Wahabbist Muslim Saudis. The demonizing of Muslims in general worked better as a causas belliin a clumsy, misdirected military response that was going to inflict a lot of collateral damage and result in Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. One might still be painted a terrorist sympathizer or even a traitor to broach the notion of some American foreign policy culpability for what happened on 9-11.

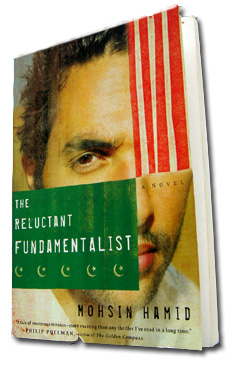

There have not been many attempts to get at the matter by other means. John Updike (Terrorist, reviewed in DCJ Archives No. 44.6) does a surprising job of imagining the compulsions and frustrations of being a Muslim in America. Is protagonist is a New Jersey half-Egyptian-half Irish high school athlete who need a father figure. But, Pakistani-born Moshin Hamid appears to draw heavily on his personal experience, having been schooled at Harvard and Princeton, much like his narrator, at plumbing the distrust between America and the Middle East. While Updike’s is perhaps appropriately a third-person narrative, Hamid speaks with a voice of direct experience, in the first person.

Hamid’s protagonist relates his story from a seat in a café on Lahore, where his audience is an American at his table. Somewhat fittingly, the American speaks little, and never directly, only indicating vague and incomplete statements repeated by the protagonist. We never “hear” the American’s voice, and the narrator is only referred to by others as Changez. The others are people with whom the narrator works in a small but high-powered investment firm where he is accepted and admired for his investment acuity. He makes good money, is given choice projects and he also meets a beautiful and rich, American woman. He relates his story to the nameless American from the Lahore café, having left America and his job to return home, apparently for good.

The girl, Erica, is perhaps the most obvious in a small cast of characters and encounters who represent various aspects of American society. Erica (the feminine derivative of a masculine name), whom Changez treats with the greatest respect, and with whom he has a tender, but ephemeral, affair, is deeply troubled by the tragic loss of an earlier boyfriend to a fatal disease. That’s America, blessed with beauty and prosperity, by flawed, and unable to really enjoy its blessings. His superior at the his workplace admires Changez and cuts a lot of slack for him when he later becomes troubled. American corporations are is able to look past the ethnicity of Changez because making money trumps prejudice, even after 911, which happens during the time frame of the story. The Pakistani is infatuated with America, but somehow it just can’t work for him. Curiously, the city in which Changez works, does work for him. “I was, in four and a half years, never an American; I was immediately a New Yorker. . . . I tend to become sentimental when I think about that city. It still occupies a place of great fondness in my heart, which is quite something, I must say, given the circumstances under which, after only eight months of residence, I would later depart.” Even Changez’s relatives entreat him to remain there.

Changez keeps returning to his one-sided discourse with the American in the cafe, each time cranking up the suspense by referring to a large, dangerous-looking waiter, or wondering if something metallic he can see in the inner pocked of the American’s coat is a gun. CIA agent, perhaps?

It is a business trip to Columbia that turns the narrator more towards the title of the book. He converses with a man names Juan-Batista whom he credits for pulling back the veil that kept him working as a minion of American capitalism and its intrusive policies around the world. Back in the Lahore café he tells the American: “Often, during my stay in your country, such comparisons [between Pakistan’s relative economic and technological backwardness in comparison with the U.S.A.] troubled me. In Fact, they did more than trouble me: they made me resentful. Four thousand years ago, we, the people of the Indus River basin, had cities that were laid out on grids and boasted underground sewers, while the ancestors of those who would invade and colonize were illiterate barbarians. Now our cities are largely unplanned, unsanitary affairs, and American had universities with endowments greater than our national budget for education. To be reminded of this disparity was, for me, to be ashamed.”

In contrast to Updike’s “terrorist,” this “fundamentalist” appears to not have a Muslim agenda. He sees the problem in more conflicted hues. His education appears to moderate his tone, keeping it closer to lament than to anger. Except for the suspense he builds as he and the American finish dinner and he offers to escort the American back to his hotel. It is dark now, and the streets in Pakistani cities can be dangerous.

____________________________________________________________

© 2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 7.6.2008)