“The new appointee was known to have behaved disgracefully with pupils since 1629, some fifteen years earlier. He repeatedly betrayed the trust laid on him as a priest and a teacher. Time after time he had been promoted away from the scene of his crime. There is no record of him ever expressing a word of remorse, guilt or reform. The members had kept silent through many years, but this appointment to universal superior, over the head of the ancient founder, was a step too far.” [p. 208]

“The new appointee was known to have behaved disgracefully with pupils since 1629, some fifteen years earlier. He repeatedly betrayed the trust laid on him as a priest and a teacher. Time after time he had been promoted away from the scene of his crime. There is no record of him ever expressing a word of remorse, guilt or reform. The members had kept silent through many years, but this appointment to universal superior, over the head of the ancient founder, was a step too far.” [p. 208]

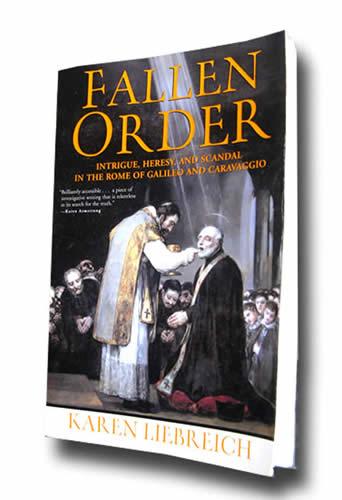

The words might have come right off the pages of a contemporary metropolitan daily—but the date is 1629. Despite what bishops, cardinals, and even popes have implied, the story of priestly child abuse is not something recently “uncovered” by the Roman Catholic Church, it has been known since the very first schools for boys were established in Rome by the Church’s Piarist Fathers in the late 16th Century. The cover-ups, the denials and excuses, the moving of priests from school to school as their misdeeds became known, are not the invention of the present-day Church hierarchy, they were practiced from the very beginning.

If abused parochial kids need a saint to supplicate it should be St. Jose de Calasanz (1557-1648), beatified in 1948. It was Calazanz’s idea to start schools for poor boys in Rome in the later 16th Century. The ascetic Spaniard founded he Piarist Order and wrote its curriculum for its schools and its “constitution” to govern the behavior of its faculty of priests. He knew from the beginning that there were dangers in putting celibate priests in charge of young boys and did what he could to install safeguards. But as the schools spread, first throughout Italy, then abroad, there was no way to control the situation. Indeed, Calasanz’s rigid asceticism—he nearly starved his priests to death—left only the appetite for sexual gratification for their otherwise unpleasant lives.

Calasanz’s inability to control the lusts of his priests eventually brought down a religious teaching order that had educated such illustrious personalities as Mozart, Shubert, Victor Hugo, and Goya among others. There is probably the stuff of a half-dozen novels about the intrigues in the Roman Catholic Church that was uncovered from dusty archives by intrepid researcher Leibreich, who had to learn Renaissance Italian in order to ferret out the sordid non-fiction. The tale has nearly everything—sex, guilt, lies, betrayals, poison, torture, and some weird diseases that seem like apt punishments for the sinners they dispatched. Throw in some sleazy popes and cardinals, the Jesuits, the Inquisition, and even Galileo and this could be an HBO series. The word is that at least on of Carravio’s paintings hung in one of the schools, and some of those were more than a trifle “suggestive” of homoeroticism.

The spark of scandal might have been caused by a Fr. Stefano Cherubini, one of he Piarist teachers. With a name like “Little Angels” it sounds like something from Central Casting, but Cherubini apparently enjoyed molesting young boys. The problem was that he came from a well-connected and well-to do family, causing Calasanz to look the other way. Preceding Cardinal Law, Calasanz shifted Fr. Gropey-hands to a job as a “visitor” to several of the schools, which, of course, only increased his predatory opportunities. Thus, the pattern of concealing rather than exposing, predatory priests was set early in the RCC educational system. Everybody knew about Cherubini’s antics, letters were written, protests ,lodged, and information went all the way to Pope Urban VIII. Nothing was done.

The Piarists had other problems. Some of their teachers from the Florentine school sided with Galileo in his heliocentric view of the universe. The Church wanted to slice and dice the great scientist, particularly the Holy Office of the Inquisition (the same Holy Office that the current pope, Benedictine XVI headed for many years). Then there were the Jesuits (much spoken about elsewhere in these pages: Archives 41.1, 37.2, 33.6, 30.6). The Jebbies didn’t much like then Piarists, unfairly, I think, because their dislike seems to have had more to do with the Galileo matter—they opposed him, too—but with social class. The Jesuits have always had a predilection for political power; they were going to educate boys from a “better class” of families, boys who would ignem mittere in terram, as the motto of St. Francis Xavier, the great Jesuit missionary, proposes. Comparatively, the Piarists were educating street scum for lowly vocations, not to be popes, business and military leaders, and great statesmen, but clerks and factota. The luminaries of the Piarists came later, and were far fewer than the stellar Jesuit alumni. Why the powerful Jesuits would see these mendicant priests as competition is not clear.

The Piarists had even more trouble from within. One of their own, a Fr. Sozzi, who liked good food, wine and clothing as much as playing Fr. Fondlefingers with the students, became an enemy of Calasanz. Moreover, he befriended the arrogant and ambitious Francesco Albizzi, the Assessor of the Inquisition, a friendship from which he was able to terrorize the leadership of the Piarists, especially Calasanz, and protect his other friend, Fr. Cherubini. Sozzi eventually was able to take over the Piarist schools, elevate Cherubini, and come closet o turning the schools into brothels for paedophiles. The chaste and ineffectual Fr. Calasanz could do little about it. The rules of he Order were relaxed, some priests created public scandals with drinking, whoring, and eventually the molestations became public. Pope Barbarini (Urban VIII) died in 1644, and when Innocent X took over the old alliances, connections and protections were broken.

Some of these guys died some creepy deaths. Sozzi contracted some sort of what was call a fungal disorder or infection that covered his entire body and killed him. Four years later his friend Cherubini died of a similar virulent skin disorder.

Calasanz, the founder of the Piarists, lived on to age ninety-one. He was plagued with liver problems, but might have lived on even longer because he refused some medicines that were the same used successfully by King James I of England. But it was medicine that was used for a “heretic.” Such was his religious conviction. Although he died with his schools in ruins, Fr. Calasanz was almost immediately headed for sainthood. It was reported that his dead body “smelled like roses” and that a woman who touched it with her crippled arm was healed. There were other miraculous claims, and people began to come to his body to tear off bits of cloth as miraculous relics. Finally, the body had become stripped of covering for all the relic harvesting and it was said that, even though dead, Calasanz’s dead hand moved to modestly cover his private parts (or was this a reflex from a lifelong practice?. He should have had as much concern for the modesty and private parts of the students in his care.

____________________________________________________________

©2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.25.2008)