The paradox of walls is that you can’t wall someone out without walling someone in. As we view with some discomfort the erection of the huge walls in Israel’s Wes Bank, a desperate and, arguably, necessary measure to fend off the terrors of suicide bombers, it is not without irony that a people who have, in their disasporic history, often been victimized by walls of stone and stigma.

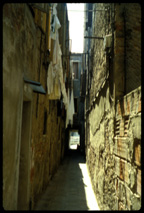

Ghetto Street ©James A. Clapp

Menorah on Jewish Shop ©James A. Clapp

Foundries of Exploitation

One of the characteristics of urban life from the earliest times has been the designation of certain spaces for specific purposes or segments of the population; temple precincts, market areas, as well as class and caste differentiated residential areas have existed from the beginning. So have ghettos. But what ghettos are, both yesterday and today, is perhaps best understood from their perspective of the place that gave us the term.

In the year 1516 the republic of Venice, Italy issued an edict that required all of its resident Jewish population to relocate to a small area of that city surrounded by canals. The little island was the site of a disused foundry for making cannons. The Venetian verb to cast metal was gettare, from which evolved the word “ghetto.” Ostensibly, the purpose of this edict was to protect the Jews from outbreaks of violence against them, although there had been relatively little such violence in Venice as compared with other cities.

So, “for their own good,” some 2,000 Jews were herded onto the tiny island, and the two bridges to it were given iron gates that were locked at sunset. Canal-facing windows were bricked-up, and the residents were given insignias for their clothing, or special hats to distinguish them from other Venetians, to wear when they were abroad in other parts of the city. As the edict specified, this could only be during the hours from daybreak to sunset. The remainder of the time they were sealed behind the gates of the ghetto, their involuntary cloister assured by police patrols by gondolas in the surrounding canals. The Ghetto residents were taxed to pay for the patrols.

Perhaps more significantly, the Jews of the ghetto were severely restricted occupationally, relegated to being clothing merchants, shipwrights, and money lenders. This last occupation was both required and reluctantly tolerated by the Venetians. Owing to the fact that the Catholic Church prohibited the loaning of money at interest by its faithful, many Jews were restricted to this work, which earned them substantial profits, and an equal measure of opprobrium. This occupation received its renowned literary documentation in Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, published seventy-four years after the establishment of the ghetto.

While the Jews of Venice did manage to establish a flourishing cultural and educational community despite the crushing density and oppressive conditions of their ghetto, they suffered the indignities of this condition for nearly three centuries, until the Napoleonic conquest finally brought down the gates in 1797. By this time, the Ghetto had expanded to conatain several thousand Jews from all points of the disaporic compass-Askenazi, Sephardic, Levantine-and with several synagogues related to different versions of their faith.

Viewed from the perspective of the time and place that gave us the term, ghettos are foundries of exploitation whose unfortunate residents are spatially and socially restricted, and limited to social roles that all but guarantee their assignment of a negative stereotype.

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.11.2004)

Excerpted from James A. Clapp, “Shylock’s Ghetto: The Place of the Play,” Places, Vol. 3, No. 2, May 1986, Pp. 40-6