The most prominent and commented upon nose in the universe might just be the customized job sported by singer Michael Jackson. Oceans of ink have been expended speculating on the number of surgeries it took to sculpt it, its curious aesthetics, and the psychological circumstances that lie behind such nasal obsession. But The Bleached One is not alone in his dissatisfaction with his original nose. Many other noses have fallen to the scalpel. But others have formed a positive relationship with their noses through History.

A Nose For The Renaissance

A Nose For The Renaissance

If you happen to be one of those people upon whom Nature has bestowed an unusually large, or oddly-shaped proboscis, it has doubtless been the object of comment by foes, and even friends. There is no disguising a prominent or unusual nose; sun glasses won’t hide it, you can’t comb your hair over it like you can with big ears, and you can’t reasonably keep it wrapped in a handkerchief for more than a few seconds unless your are being tear-gassed. No, your nose has to be out there performing its olfactory and respiratory jobs, for all to see . . . and ridicule.

I should know. My nose didn’t start off all that badly. Actually it was sort of cute and curt for a few years, as are most kids’ noses. But by teenage it took on a Pinocchio -ish growth rate and had lost a couple of battles with fists and another with a football helmet. In consequence today my nose from a bad angle resembles Yasser Arafat’s nose from a good angle (Is that possible?).

So, I avoid profile photos. I avoid photos as much as possible.

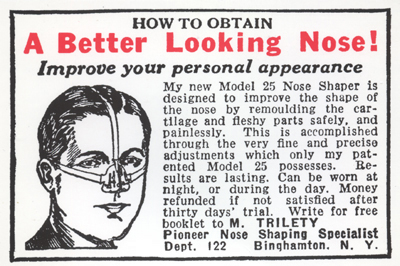

Long before cosmetic surgery became almost routine I considered various methods to deal with my unhappiness over my nose. For years I kept a clipping of an advertisement I clipped from the back of a magazine that also had ads for building a physique capable of repelling bullies who kicked sand in your face at the beach.

I practiced clever ripostes for verbal assaults on my nose. “Shut up or I’ll peck you to death!” was one of my favorites. Or, “Did you skip your annual bath? I could smell you before you left your house this morning.” But, of course, these cracks only drew more attention to what I really wanted to hide.

It wasn’t until college, when I was researching a paper on the Italian Renaissance, that my relationship with my nose improved markedly. The Renaissance, as everyone knows, or should know, is one of the most important periods in the history of Western Civilization. It is a period which, because of the re-discovery of antiquity and the changes it engendered in art, science, and philosophy, stands out in history like . . .a . . .well, why not, like a prominent nose.

Now I was interested in the art, science and philosophy of the Renaissance, but what really caught my eye were the noses they had back in the Renaissance. Consider this. If you have an unusual nose, you share a physical feature with many of the great figures of the Renaissance. Take Michelangelo, for example, a bronze bust of him in the Museo Nazionale in Florence shows a mashed-in prizefighter’s nose. His nose actually was busted up during a fight in the artist’s youth.

Michelangelo is buried in the same church as Machiavelli, whose name has become an eponym for political craftiness. As Santi di Tito’s portrait of him shows, the long, weasel snout of the philosopher, which ends in a pendulous drip, may have contributed to his unwarranted reputation. Machiavelli wrote about Renaissance princes, like Duke Federigo Montefeltro of Urbino. Montefeltro was a model of the warrior-scholar-prince, and portraits, which often show him studying in full armor also show a bizarre, hatchet nose that was created by a sword slash that also disfigued his right eye. That explains why he still preferred to be painted only in profile, unflattering as that may be.

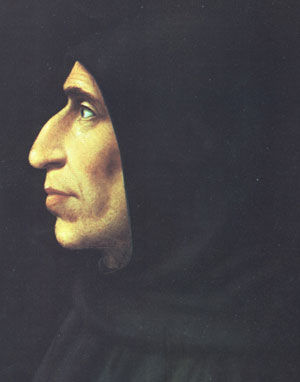

What is flattering to appearance, or not, is, of course, subject to times and customs, and one almost gets the impression that unusual noses were prized in the 15th Century. The firey Dominican monk Savanarola also allowed himself to be portraited in profile, as if wishing to highlight a tremendous hawk-like nose as fierce as his personality. After bringing down the Medici in 1494 Savanarola was excommunicated and burned at the stake in 1498, but it must have taken an extra log or two just to fry the friar’s beak.

Then there was the man Savanarola brought down, Lorenzo de Medici, called il Magnifico , an appellation that might have applied to his nose as much as his many talents as a banker, patron of the arts and civic administrator. The bridge of Lorenzo’s gnarled nose changes direction of descent at least three times and grotesquely flares out at the nostrils according to a bust of him by Verrocchio. Still, for all of his money, he chose not to bribe his sculptor to put some cutesy little turned-up job on his bust. Lorenzo must have liked his nose even if, as a biographer tells us, it had no sense of smell.

One could go on an on; weird, wild and wonderful noses abound in the Renaissance. Just check out portraits or busts of Galleazo Sforza of Milan, Francis I of France, and many other notables. They proudly display rhiniferous contortions that would drive a contemporary man to a plastic surgeon. Sure, there are some modestly, sized, straight noses here and there, but it almost inevitably turns out that they belong to people without much talent. The real people behind the magnificent achievements of the Renaissance and by extensions many of the achievements of the modern age, are the people behind those amazing noses. It’s a plain as the nose on your face.

So, maybe my nose was born about five-hundred years too late. But I’m on much better terms with it now that I know it had such illustrious and interesting ancestors back in the Renaissance. Maybe we should make that the “Rhinossance.”

___________________________________

©1989, ©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.4.2004)

“Noses for the Renaissance,” KPBS-FM, Aired August 4, 1989