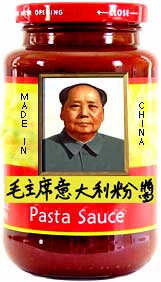

Great Helmsman Pasta Sauce with Mushrooms and Duck Gizzards

© 2004, UrbisMedia

The neologism one hears more and more in these days of globalization is “out-sourcing.” You know, that’s when you send a job out to be done by somebody else, increasingly somewhere else, sometimes better, but usually at a lower cost because of less regulations, lower wage rates, or cheaper overhead. Lots of things can be outsourced, maybe just about anything. And that’s the concern. Out-sourcing, tucked in the broader linguistic envelope of globalization, is one of the newest, and critical, political issues in America.

But is out-sourcing all that new? I think not. I think it has been around for some time. I’m Italian-American, and I have a relative who was an originator many years ago of something that we take very much for granted today—pasta sauce in a jar. When I was a kid, all pasta sauce was made by mom, right at home, in an American (OK, Italian-American) kitchen. But then, with my cousin, who, by the way used his mother’s recipe, came the convenience of pasta sauce in a jar, made by somebody else.

Yup, the precursor to outsourcing was out-saucing. Now mom’s don’t have to slave over huge pots of sauce on kitchen stoves when they can go to the supermarket and pick up a jar of marinara or alfredo, right off the shelf. This remains heresy to pasta sauce purists, but the numbers don’t lie. Out-saucing is a success; my cousin, and his fellow out-saucers made millions. The concept doesn’t lie either: if we can get somebody else to do the dirty, hard, or drudge work, for less that we would pay ourselves, then we’ll usually go for it. But it can also work for stockholders as well as consumers. If they can increase their share value by out-sourcing, they’ll usually go for it.

We started out-sourcing with product assembly, which is one of the reasons so many products say “Made in China,” and then with outright manufacturing of products (made in China and a lot of other places), to, most recently, the outsourcing of information processing and other services to places like India, China and Mexico. The latter has proved to be doubly efficient since the cost transmission of the raw material for information processing is almost negligible. Now your city tax bill, or a support call on your computer software, among an expanding list of other services, might be coming from Bangalore, Mexico City, or Shenzhen.. (“Nihao, I mean Hello. My name is Wang Xiao Pei, same initials as Windows XP. But you can call me “Crash.” Your call might be recorded for quality assurance . . . “).

What makes this a hot political issue is that American workers are feeling threatened at more turns by foreign labor. People who used to work on the toys, appliances and apparel that have been outsourced might seek retraining and job security in high-tech computer-based jobs. But now those are being outsourced as well. Much like my cousin’s mother’s recipe, most of the hardware and software were developed by American R and D. Some see this as the future for American workers, but these jobs are scarcer because they are at the top of the employment “food chain.”

What might be called “in-sourcing” is also a concern. This is where immigration, both legal and undocumented, is seen by some as driving down domestic wage rates in already low wage industries, making the Bush Administration’s amnesty policy double-edged both politically as well as economically.

Much of this is the result of several of the canons of American economic ideology—competition, de-regulation, free trade, etc.—coming back to bite us. With the fall of less efficient systems, like communism and feudalism, other countries with huge labor pools are now in play in the globalized economy. American’s who have wanted countries like China, India and Russia to be “more like us” may end up regretting getting what they wished for. At least we will have to find our new place in the globalized economy we helped create, and for enough of our workers to maintain our vaunted “American way of life.” Before that happens we might well see “Made in China” on a jar of pasta sauce. (Well, they do claim to have invented pasta).

Meanwhile we are likely to have a lot of political discourse on this subject, although it might be more pleasant if we could out-source some of that as well.

___________________________________

©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.23.2004)