I can’t remember the last time I saw anyone on the streets of San Diego consulting a street map. For that matter, I can’t remember seeing anyone on the streets of San Diego whose car wasn’t in for repairs, or wasn’t homeless? I’m exaggerating a bit, but no so much in the matter of consulting street maps.

Not so in Paris, where I have lived in 1989 and 1999, and where one often encounters native Parisians scanning the pocket-sized Paris Par Arrondissement , a vademecum with maps of neighborhoods, Metro and bus maps, street lists, and much more. Cab drivers and commuters, young and old, “don’t leave home without it.” And even if they do there are maps everywhere in Paris, in Metro stations, at bus stops, intersections, and train stations.

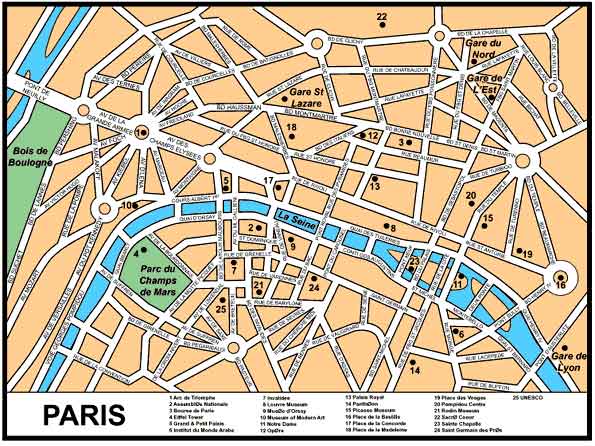

The reason for the ubiquity of these indispensable aids to navigation is most immediately appreciated by a glance at a general map of Paris, which shows that the city has a configuration not unlike that of a spider’s web. The main traffic arteries of Paris fan out from several etiole (stars), or traffic circles that may form the confluence of as many as a dozen boulevards.

Paris wasn’t always this way; this feature in particular derives from the 1870s, when Louis Napoleon commissioned Baron Haussmann to re-design the entire city. This Haussmann did with an authority and abandon the likes of which few city planners before or since have exercised. Boulevards were driven through narrow-streeted old quarters, sewers emplaced, trees planted, and parks created in an almost ruthless process that outraged much of the citizenry. Similar to today’s epithet in San Diego called “Losangelisization,” the re-shaping of Paris was referred to as the dreaded “Hausmannization.”

Yet, in the curious ways of cities, the Haussmann Plan is seen today as perhaps the single-most influential public enterprise that gives Paris is special style and urban beauty. Those broad boulevards accommodate traffic and parking better than most European cities, create grand vistas focusing on buildings and monuments, and provide shady promenades lined with cafes and brasseries. Driving into anetoile may require the sang froid of a grand prix driver, but then that is precisely what every French driver considers himself to be.

Yet, in the curious ways of cities, the Haussmann Plan is seen today as perhaps the single-most influential public enterprise that gives Paris is special style and urban beauty. Those broad boulevards accommodate traffic and parking better than most European cities, create grand vistas focusing on buildings and monuments, and provide shady promenades lined with cafes and brasseries. Driving into anetoile may require the sang froid of a grand prix driver, but then that is precisely what every French driver considers himself to be.

But the efforts of Napoleon and Haussmann were not inspired by anticipation of the automobile. Rather, the motivation for the revolutionary re-design was revolution itself, or more precisely its prevention. Paris had had enough revolutions for several cities since the big one in 1789, and each time those revolting Parisians had frustrated counter-revolutionary forces by blocking up the narrow medieval streets with barricades. The new Napoleon had reason enough to be concerned about such tactics. He had come into power by election, but then decided to declare himself emperor, just like his more renowned uncle. So Louis and Haussmann cleaved the old neighborhoods with boulevards to make them more difficult to barricade and to facilitate the movements of troops and cannon.

As things turned out this politically inspired planning didn’t save Napoleon’s empire, but it did give Paris the look and feel we are familiar with today. The plan made Paris pretty alright, but it also made it pretty confusing; there isn’t a right angle or simple north-south direction in the entire city.

To add a bit more spice to things the Parisians have this tendency to use their streets as a course in this history of Western Civilization. Unlike Manhattan with its numbered streets and avenues, or other American cities that employ numbers or the alphabet for street names, Parisians prefer people, places and events for street names. Taking the opposite approach as San Diego, which can’t seem to get one street named for Martin Luther King, Jr., the Parisians have decided to name a street for everybody—painters, poets, politicians, generals, scientists, musicians, sculptors, writers, revolutionaries, saints and sinners. Name a renowned historical figure and he or she likely has a street in Paris. Even famous Americans like Franklin, Wilson, Roosevelt and Kennedy have their Paris streets. In fact, there are so many famous people, places and events to be honored that single streets have been divided up in order to accommodate them all. Thus, within a length of a few blocks the Blvd. de la Madeleine changes to Blvd. des Capucines, to Blvd. des Italiens, to boulevards Mommartre, Poissionier, Nouvell, St. Denis and St. Martin—one street with eight names. Still there are a few people who have been not honored; the current flap is whether Robespierre should get one. There’s not much room left, but it wouldn’t be inappropriate to “chop off” a block somewhere to give him a place on the Paris street map.

In the final analysis, between Hausmann’s politically motivated city planning and the Parisian practice of street-naming, we might have seen the last of revolutions in the thoroughfares of Paris. After all, it’s not easy to conduct a revolution or a counter-revolution with a rifle in one hand and a street map in the other.

___________________________________

©1989, ©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 2.22.2004)

Radio Essay No. 42,aired KPBS-FM, Public Radio, July 12, 1989