©2008 UrbisMedia

Many years ago I was in Hall 15, The Leonardo Room of the renowned Uffizi Gallery in Florence. At one end of this particular room was, on an easel and behind a velvet rope guard, Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Annunciation.” I happened to be perusing Perugino’s “Pietá” when in walked a local Italian guide at the head of a group of uniformed English high school girls.

The guide, no taller than the girls, reminded me of the 1940s bit actor, Dane Clarke. He wore his sunglasses on top of his head and had his sport jacket on his shoulders, arms outside the sleeves, an Italic affectation. He strutted, as though the salle was his own living room, up to the rope guard, where he stood with his back to the twittering schoolgirls. There he waited, not saying a word, until his pause caused the them to quiet down. I was intrigued. This was a performance by a guy who felt he had mastered his craft. Heb had my attention.

Presently, he turned and faced the girls. Peering over their shoulders I could just see his head. There were tears in his eyes! He waited a few beats longer, then intoned, in that Italic-accented English of Vittorio De Sica, “Young ladies, I have been before this magnificent painting by Maestro Da Vinci many, many times. But, each time, I am so moved by its beauty and the wonder of the subject.” He then went on to deliver an interesting explanation of the painting, the three-quarter pose on the Virgin, Da Vinci’s use of areal perspective and, especially, the angel.

He had them in the palm of his hand. The girls were fixed on the beautiful angel as he went on about the annunciation the angel made to Mary. Then he focused on the angel’s wings, and how Da Vinci had rendered them, how realistic they were. He compared them with the silly little wings of putti in other paintings of the time, how Da Vinci’s feathers were so life-like. He explained that Da Vinci had studied birds and did many sketches of the movement of their wings inn flight. Then he said something that seemed strange: “Young ladies, you look at those wings and you know, you know, that that angel can fly!”

Was it the professor in me? Something in me wanted to shout, “bullshit!” Something in me wanted to say, “that angel couldn’t get a foot off the ground with those wings!” First of all, the wings are too small. I knew that Da Vinci had studied birds, that he was very interested in flight. But he had also studied human anatomy as well. He was the guy who snuck into morgues at night to dissect bodies to see how they were constructed. So, I was convinced that, had Da Vinci been standing beside me, he would have shouted “bullshit,” or merda de toro, or something like that, even though it was his painting. Da Vinci would have known that, in order to drive those wings he painted, that angel would have needed about eight times the muscle mass in his chest—he would have required a chest, with protruding breastbone, like a condor, not like a cute boy. Da Vinci didn’t want to paint an ugly, physically-distorted angel, the patron would have rejected it with an angel that looked like Dolly Parton.

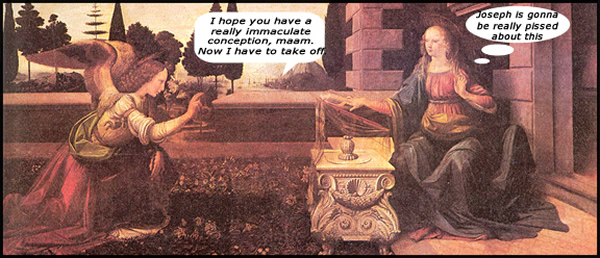

Why Mr. Guide decided to spoil an interesting discussion of painting technique with a literal flight of fancy, I don’t know. Maybe he just got too full of himself. Or, perhaps he just didn’t want to deal with the real subject of the painting—the “annunciation.” Did he not want to deal with a question from one of the school girls (he surely would have got one from me) about what this angel was announcing—that Mary had been selected by God to bear His Son, the Messiah, and that Joseph, her husband was not going to be the impregnator-father of who would become the most famous kid in history? Did he not want to have to try to make credible this ludicrous story cocked up by some fathers of the Church. How could he defend the Immaculate Conception when, if pressed, he couldn’t make a credible anatomical case for a flying angel?

It is a painting of a myth. Da Vinci knew that. He would have had the angel arrive in a helicopter (he had a design for one) if the patron had wanted it. Of course, most religious painting of the time was commissioned and paid for by the Church or believers and they preferred their myths beautifully rendered in art and, if their angels had to fly, they would crank them up and down with an aptly-named deus ex machina.

The Annunciation was a Renaissance painting, and though Da Vinci employed enough realism to convince the patron and the viewer that the angel was capable of flight, he knew the limits of faith and reason in artistic representation. (He also probably didn’t want to have the kind of experience that Galileo endured later on.)

This was a period of the beginning of the end for the Church in the “faith and reason” debate. Da Vinci was one of the first to start to take Nature apart and look at it (the Church forbade dissections at the time). There were many others to follow who wanted their art to reflect a realism that came from the growing interest in optics, perspective, mathematics, geography, and other sciences. For centuries, the Church remained the prime patron for the arts. Realism took a back seat, and the purpose of art was to inspire and elevate the spirit, not to dissect Nature and enlighten. But faith had to enter into a Faustian compact with science if cathedrals were not to fall down and if Biblical events were to be represented as though they really did happen. The purveyors of belief could get away with it so long as it was not necessary for angles to fly out of paintings after they had delivered their “annunciations.” But eventually somebody had to have enough of it all and shout: “Bullshit!”

___________________________________

© 2000, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.30.2008)