One of the more endearing images I have of a recent visit to Beijing is of a university student peddling down a street on a dilapidated Mao-era Tianjin “Silver Pigeon.” His girlfriend rides side-saddle on the rear carrier, one arm around his waist, the other hand holding a book she is reading while resting her head against his back. There is something romantic about this vision, harkening back to the days when untold numbers of bikes plied Beijing streets with the only the sounds of creaking chains and tinkling warning bells, a vast peloton of placidity.

One of the more endearing images I have of a recent visit to Beijing is of a university student peddling down a street on a dilapidated Mao-era Tianjin “Silver Pigeon.” His girlfriend rides side-saddle on the rear carrier, one arm around his waist, the other hand holding a book she is reading while resting her head against his back. There is something romantic about this vision, harkening back to the days when untold numbers of bikes plied Beijing streets with the only the sounds of creaking chains and tinkling warning bells, a vast peloton of placidity.

The image I saw of this couple was nearly wiped out by a $70,000 Mercedes Benz that gave the bike and its riders absolutely no quarter despite being in a bike lane. It doesn’t matter whether it is a couple of students, and old man on one of those motorize trikes, or some delivery person hauling freight on some ancient tricycle, cars rule in Beijing these days. Pedestrians don’t have the right of way, but they are, by law, I am informed, not at fault when they get clobbered by some flashy, expensive sedan. That law is all that stands between people on foot and a lot more greasy spots in the road. The rich do not want to pay, but they play it as close to the bone as they can.

I have a special feeling for this subject. As I am being ferried between the university, where I am giving some lectures, and my hotel, and around town to see the various Olympic sites and the incredible new architecture in this city of 18 million and growing, I am myself still healing from being whacked by a truck while riding my moped in San Diego, still changing wound dressings every other day. I cringe every time a car brakes hard to avoid plowing into a group of pedestrians.

At the same time there is a surprising level of tolerance of the drivers for one another. Following the general Chinese rule if leaving no space unfilled, drivers cut one another off with an intrusiveness that, in the U.S., would result in expletives, flip-offs, and shoot-outs, by the millions. Thusfar, there seems to be no road rage in Beijing. There also do not seem to be any rules of he road. The scene on Beijing’s roads seems like a massive demolition derby about to happen. They honk, they neglect to signal, they change lanes like wildebeest fleeing a cheetah, they park when and where they like. In short, they love their newfound, damn cars. This is the new China, where Deng Xiao-ping said “to get rich is glorious” and, I presume “to change lanes without signaling is downright fun.”

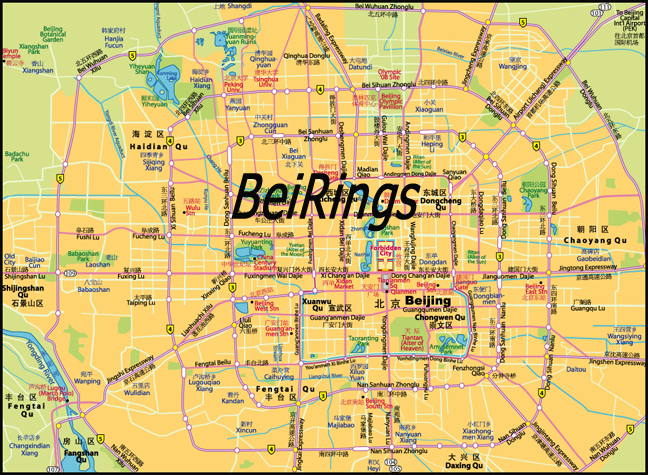

This was my 6th visit to Beijing but, as far as appearances were concerned it could almost have been my first; the place changes that rapidly. The 2008 Summer Olympics, when added to China’s decade-long economic boom, have made Beijing a city on steroids. If cities can suffer from Marfan’s Syndrome Beijing has that as well. If you are getting a little too big for your own ego, come to Beijing; it will cut you down to size with one circuit around the ring roads.

Beijing has developed as a rather orthogonal city, taking its rectilinear form from the cardinal directions of the Forbidden City. That royal compound, like the core of a tree, has dictated successive “rings,” or ring roads, now up to six, that give Beijing its distinctive, and its inexorably expansive plan. It makes travel about the city primarily “circumferential,” necessitating a hopping between rings to achieve radial direction. It is probably rather inefficient, extending travel times and sending more hydrocarbons into the atmosphere than necessary.

This latter effect seems to be producing an atmosphere in which cars will need to come equipped with radar or sonar, whichever is more effective for navigation in a blinding carboniferous soup that literally can reduce visibility to a hundred meters. Regular horns will need to be replace with fog horns if the particulate matter densifies any further. It seems as if this giant metropolis is engaged in a reciprocal dance in which the rising number of automobiles is both accommodated and necessitated—a Faustian compact with seems to threaten a denoument of mass asphyxiation.

So, from the beginning it may not have been a good location for a capitol city, or any city at all. It was a decision that was made by the Mongols (a traditionally nomadic people with little or no discernable principles of city planning). They selected the eastern edge of a desert from which the Westerlies blow dust that produces a lot of hawking and not always effective signs that read “No Spitting.” Surrounding mountains help in the formation of temperature inversions that make things nice and smoggy.

Beijing’s low visibility might explain another feature of its recent urbanism—“monumentalism.” The city has sprouted hundreds of huge buildings. Massive apartment blocks, giant malls, towering office structures, and of course, the new Olympic structures, such as the “Bird’s Nest” field stadium, and the huge block of icy blue that is the aquatic sports venue. Soaring ancillary structures, one a building whose top stories are designed to simulate the Olympic torch, surround the Olympic site. The gigantic new television structure, an arch that makes the one at Paris’s La Defense look like a Lego toy, seems to defy gravity and the laws of physics. Down below thousands of workers are panting trees, re-paving sidewalks, and making other cosmetic changes in a seeming frantic effort to be ready for the onslaught of “foreign devils” at the opening ceremony. An incredible and beautiful new elliptical dome opera house reminiscent of the spaceship that landed in Washington D.C. in the movie, The Day the Earth Stood Still, sits in a pond that reflects and doubles its volume.

The monumental scale of all these structures seems almost necessitated by the corresponding scale of the vast ringed metropolis. Being driven around by my gracious hosts I never seemed close to them as the loomed in and out of the grey gloom of Beijing’s atmosphere. At various locations in the interstices there still remain some of the relatively ancient hutongs, the compounds of narrow lanes and cramped houses, often without plumbing and gas, but reminders of a more accessible and far less forbidding Beijing of not very long ago. But these, too, are being threatened by the relentless horizontal and vertical urban expansion.

Beijing is truly transforming itself into the world city its leaders want it to be, but will the people who call themselves “Beijinese” have anything of their old city to remember it by?

___________________________________

© 2008, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.25.2008)