There is a young computer engineer, in his early thirties perhaps, who comes to the café I frequent. He’s a stoner, but has managed to get by the drug tests of the Asian-owned company he unhappily works for. I can write about him because he doesn’t read my site. He is a handsome, strapping lad, and one might axiomatically think he is fortunate in is looks and education. He looks more like a jock than a guy who stays in a haze of cannabis-induced paranoia. I call him “Boomer.”

There is a young computer engineer, in his early thirties perhaps, who comes to the café I frequent. He’s a stoner, but has managed to get by the drug tests of the Asian-owned company he unhappily works for. I can write about him because he doesn’t read my site. He is a handsome, strapping lad, and one might axiomatically think he is fortunate in is looks and education. He looks more like a jock than a guy who stays in a haze of cannabis-induced paranoia. I call him “Boomer.”

Boomer talks enough about the need “to blow up rich people” to disabuse one of he notion that he would actually do it. He smiles when I say, “have a seat Boomer,” or give him a little mock salute of a thumb pushing down on my fist as though it were a detonator. I invite him to sit down because I am curious as to why he is so oppressed by the work and his circumstances. He complains about women, saying he can’t find one who isn’t “a feminist.” He’s very categorical.

Some people might say I should watch out for this guy, that he just might be the type to strap a couple of pounds of C4 and bags of nails and carry out his fantasies. Then again, he might be just a guy who can’t handle his world, that does too much grass and reads too much sci-fi, but is harmless to everyone but himself. But what makes me curious about him is that he just might be a boomer, and I want to know what kind a mind it takes to to push that thumb down on a real detonator.

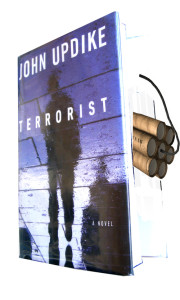

Updike has the same curiosity, and he plunges the reader into the Qu’ran-addled mind of Ahmed Mulloy, a half-Arab-half-Irish-American New Jersey high school track runner and student of a local imam. The time is post 9-11, when America is waiting for the next attack from Al Qaeda. Ahmad is filled with all the Islamic fervor of a kid in the vortex of an absent father, a loving hard-working nurse mother trying to find some love for her self in all the wrong men, a neighborhood full of dissolute minorities, and his pumping testosterone. Ahmad is obsessed with remaining Islamic-ly “clean” in the midst of such corrosive forces. Ahmad is not an angry impoverished ghetto-snipe, but a lower middle-class kid with a chance. [1]

Consistent with Updike’s style it is a tight and well-defined dramatis personae: the imam, spouting the most bellicose suras from the Qu-ran; a local Black girl, who puzzles Ahmad with her sexuality and participation in the gospel choir at her Baptist church; a concerned Jewish guidance counselor who ends up bedding Ahmad’s mother; a fellow Americanized-Arab who “recruits” the young wannabe truck driver into being a suicide-bomber Timothy McVey.

Updike’s is a third-person account, but the perspective is skewed to Ahmad; he is after all the titular role. He is the incipient “boomer” we are most interested in. Updike draws him in details your average Bushie has not been conditioned to consider—handsome, respectful (he’s far more respectful of Joryleen, the Black girl than is Tylenol her Black boyfriend who whores her out), and struggling to be a good student. But he is battered by the clash of the rigid dualities of the Muslim faith and the messy contradictions of America’s open-ended consumerism, tenuous adherence to its principles and ideals, its fat, self-indulgent, and worst of all, in Muslim terms, infidel godlessness. Updike draws from the holy book to demonstrate how Ahmad’s mind (not thought processes) is being shaped. Mohammad is Allah’s apostle. Those who follow him are ruthless to the unbelievers but merciful to one another.” [2]

The reader suspects early that Ahmad’s rejection of going to college and his interest in becoming a truck driver are plot-laying for what kind of boomer he is destined to become. But we are kept page-turning by the where and when. Updike’s economy assures us that he will pay off most everything that he sets up, so that Counselor Levy and Ahmad’s mother not only serve as an erotic sidebar, but also as icons for non-practitioners of Judaism and Catholicism, and Levy and his porky wife even figure into the denouement.

The American picture the author paints is not appealing, a country that has become inward-looking, xenophobic, and largely concerned with the garbage of its own consumption. The ironically-named town of New Prospect, is a grotty mess of derelict strip malls, one of those innumerable marginal places in the American quasi-urban wasteland that are being surrendered to cheap, reflexive, addictive consumerism—urban Wal Marts. It disgusts Ahmad, but he only has his literal and mindless suras as a guide, and they only lead him toward suicide bombing, anistishhadi, as his ticket to some dorky notion of paradise.

Updike skills as a writer of dense, by apprehensible prose seem undiminished. As an observer of American urbanism at its edges, especially in the northeast, he has long and laudable credentials. In this book as in others, he tends to depress this reader. But one also feels “informed”; Ahmad is not just some crazed raghead who “hates America’s freedom.” He’s actually a rather likeable, if closed off sort. Seeing America through his (Updike’s) field of vision, one begins to wonder if it is Americans who hate America’s freedom. There is a sense of drowning in his American stories. He lets you come up for a desperate breath at the end, but you are still just floating.

I’m thinking of recommending this book to Boomer next time he goes off about “killing all the rich people.”

___________________________________

©2007, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.23.2007)

[1] Socio-economically, he is, of course, much like the 9-11 perpetrators. Mohammad Atta had a degree in Architecture from Cairo and was registered as a student of (yikes!) urban planning at a university in Germany.

[2] This was obviously written before the Sunni-Shia Schism. Muslims do a pretty good ruthless job on one another when the appropriate succession to the Prophet is up for grabs.