© 2007 UrbisMedia

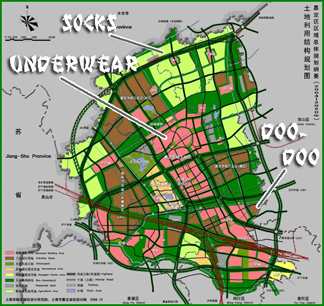

I used to half-seriously tell my urban planning grad students that, if they were the type of people who kept there socks neatly in their sock drawer and their underwear neatly in their underwear drawer, they probably would make good planners. Planning, I added, again in over-simplification, is ultimately about the old adage “a place for everything, and everything in its place.” Probably in the very first Neoloithic villages there was some guy named Urk who said, “Hey, why don’t we put the place where we make doo-doo down wind from the place where we eat.” Then somebody said, “Good idea, let’s make Urk our city planner.” Simple as that. Well maybe not quite that simple; there probably was some developer named Buk who owned some property upwind of the doo-doo place. The goodness of an idea doesn’t guarantee its implementation.

But in truth, I only half-subscribed to the principle of “a place for everything and everything in its place.” The aesthetic side of my urbanism wouldn’t me full-hearted advocacy. I recall, after writing a book on new towns—comprehensively-planned communities—and then visiting a few of them when I first came to California, that my first impression is that they were well-planned (everything in its proper place), but my second was that I wouldn’t want to live in any of them. It was my first direct encounter with the realization that all that makes cities interesting cannot be either imagined by planners, or brought into being by the methods and tools available to them. I began to imagine that sometimes it is interesting, as it were, to find a pair of boxer shorts in your sock drawer. A little surprise—in a city at least—is a good thing.

I have written often in these pages about Hong Kong, a city that I have lived in, visit often, and for reasons some of my friends can’t quite understand, I find continually alluring and interesting. My reasons aren’t even those the Hong Kong Tourist Authority might reckon (great shopping and lots of places to eat). It’s the contrasts and contradictions in its urbanism that fascinate me. If you approach Hong Kong by sea from the East you will sail past vast forests of identical residential high-rise buildings that look like cluster of crystal. Hives is my first thought. My second, and related, thought it that there is no opportunity for the people who live in them to articulate their living space (except in very marginal ways internally) to express anything of themselves. Everything as been planned for them by the architects and engineers of the building. Everything is in its place. I wouldn’t want to live there either.

Elsewhere in Hong Kong there are older neighborhoods where it is evident that people have some ability to give some shape to their physical environment. At the street level shops are built into spaces between buildings, a little crevice of space will be turned into a shoe repair, in lanes a few feet wide booths will be erected selling all sorts of foods and commodities, signs clamor for you attention over the streets and from any vantage, people build balconies on their flats (sometimes not very well) and hang their clothes to dry from them, they use roof-tops for all manner of activities—in short, they defy restriction and regimentation. These are the parts of Hong Kong that, and any city, invite and fascinate me. They are the areas where one can see “the hand” of humans as place -makers, not just space -occupiers. True, you can end up with some things that are problematic, incompatibilities and conflicts—planners even have a term for such things, called “non- conforming uses” (like a sock in your underwear drawer).

Therein is the issue joined. If you want to see conformity at its extremes you can go to Pyongyang and see people like automata, and the army marching like brain-dead drones, where every activity has a rule and a prison sentence to back it up. This is the image that Republicans like to call up if planners even suggest that there ought to be a zoning law that prohibits opening a gun shop next to a schoolyard. Somewhere between the genes of Kim Jong Il and George Bush is a reasonable place.

Planners need to be more like Einstein because it is the nature of urbanism that everything is in some relation to everything else. Put down one land use, let’s say a temple because somebody thinks this is where some god or goddess resides, and the land—and its value—change. Somebody sets up a food stall for worshippers, another a shop that sells religious articles, a soothsayer sets up a booth, people who want to live near a holy place start to build residences, religious schools come into being, and so on. Gravity is another favorite word of planners. Civic authority becomes necessitated, to provide access and safety, and of course to tell the people where they can and cannot make doo-doo.That is the magic of urbanism, suddenly space becomes place, value is created seemingly from nothing because now the land has urban utility .

The concerns of safety and efficiency of cities are in constant dynamic tension with the concerns of democracy and individuation. And here enters a term that the planer cannot live without, but does not always find it easy to live with—the Pubic Interest. We certainly do not want chaos and anarchy, so we must consent to some rules and regulations that we must adhere to. But where is the line; where do we say this or that law is too confining, this or that regulation is too binding. Reasonable minds can differ, which is why cities need to be places of democracy.

In the urban context everyone has an interest. And these interests exist in a dynamic and functional relationship to one another. Cities are the product of specialization of labor, which means that the various components of all sorts of productive enterprises in the City are carried out by different workers. This economic interdependence requires public cooperation if the whole thing is going to hold together. Once the interests of one cohort gains too much power and acts in a manner that diminishes that of another segment of the process inefficiencies and dysfunctionalities begin to enter. So planners also need to be teachers of what I like to call civic consciousness. They need to be more than designers, engineers, economists, architects, and environmentalists; they need to help people understand that planning our cities is more than about how we keep our underwear organized and where we put our places for making doo-doo. It’s much more than about the product; it’s about the process .

___________________________________

©2007, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 6.11.2007)