Many cities in America now have streets named after Martin Luther King, some of them streets on which he led marches and was hauled off from to local jails. There is now a recently published book (video review on CNN) about streets bearing the name of the great civil rights leader. But the process of honoring King with slabs of American pavement has not always been smooth. In San Diego in 1987 the City renamed Market Street to Martin Luther King Way. But the businesses along he commercial street pushed for a referendum that returned it to its original name that same year. In return King was accorded a segment of freeway 94 that runes from downtown San Diego to the city of La Mesa. At least he has more lanes and a higher speed limit.

The following newspaper piece was published in the midst of the street naming controversy.

. . . Thank God Almighty, a Street at Last

In some respects it appears that the Market Street-Martin Luther King Way controversy currently working its divisiveness in San Diego politics is much ado about very little. After all, Market Street will be Market Street whatever name is placed at its undistinguished intersections. My initial reaction to the furor perhaps trivialized the debate: why couldn’t our politicians, those practitioners of the “art of compromise” simply nominate, this shabby byway as “Market Luther King Way,” and, with Solomonic wisdom, split the difference between the querulous factions.

Whether the controversy will end up as a minor footnote in San Diego history or fester into something akin to a local Dreyfus affair is yet to be learned. There may already have been several political lessons in this sorry matter; but it appears that there are other, perhaps less consequential, lessons as well.

It would seem that the initial naming of streets is a relatively indisputable matter. The choice of employing letters or numbers as in “A” Street or “23rd Street” or the names of plants, animals, states, or even the names of developers’ children or pets, such as Debbie Drive or Rover Road, is generally cause for little concern. But once named, allegiances to these arbitrary choices crystallize not only around such matters as known business and residential addresses, but around more subtle symbolic and psychological factors as well, and re-naming streets can prove politically complicated. And when the intent in naming or re-naming a street is to honor or remember a particular individual other associations and meanings compound the issue. Then the intrinsic neutrality of a “29th Street” or a “Broadway” gives way to partisan feelings; a lifelong Republican may bristle at having to reside or do business on a Kennedy Street, or a Catholic on John Wesley Boulevard, etc.

The French have a penchant for naming many of their streets for renowned personalities, a practice with often excessive as well as bewildering results. Within a five-block stretch in Paris, for example, one street changes from “rue Auguste Comte,” to “rue de l’Abbe,” to “rue Erasmus,” to “rue Brossiolette,” to “rue John Calvin”—one street with historical associations and philosophical allegiances for nearly everybody. However, trying to find one’s way around Paris is like speed-reading Arnold Toynbee.

At another level, the Market St./King Way dispute might be seen as a failure in political communication that is mirrored in the failure of social communication in our streets. The automobile is the sovereign of the American street, which is designed chiefly for its movement and storage—broad and orthogonal. Outside of their mobile cocoons Americans are ill-at-ease with their streets, which have little to offer the pedestrian in the way of interest, variety, relaxation, or entertainment. Sidewalk cafés are rare, piazzas (or squares) and small parks even more scarce. Businesses and their signs are designed to snare the motorist, not the pedestrian, and building facades are gap-toothed by the parking lots. As either the cause or effect of these characteristics, Americans are not “street people,” a rather pathetic term reserved for unfortunates without cars or no better place to be.

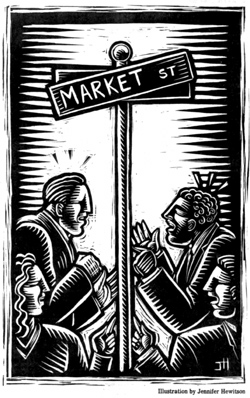

If there is an antithesis to the American street it is the to be found in Italy, where the street is the prime medium of communication. Much narrower, flanked by mixtures of residential and commercial buildings, changing in elevation and direction, enlivened by sidewalk cafes, spilling into piazzas, adorned with fountains, staircases and statuary, streets are the public living rooms of Italian cities. Although the pedestrian must increasingly share the street with overabundant Fiats and Vespas, the Italian street remains the central meeting place for friends, for al fresco dining, political debate and demonstration. It functions as an entertainment center filled with all the histrionics and animation of conversation, courtship rituals, arguing, public displays of affection, the circadian choreography of strolling, and the mime of Italian gesticulation. In Italy all the people are “street people.”

I am not about to suggest that we transform San Diego into an Italian town. We are, after all, a different culture; but increasingly we are a culture that communicates in our streets almost solely by means of vanity license plates, bumper stickers, baby-on-board signs, obscene gestures, and identifying each other by the maxim that “you are what you drive.” Perhaps if we could improve the communication in our streets we might be able to eliminate some of the discord and contentiousness we have created about our streets.

___________________________________

©1991, ©2004, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 1.16.2004)

Excerpted from “What’s in a Name?” The San Diego Union, February, 17, 1991