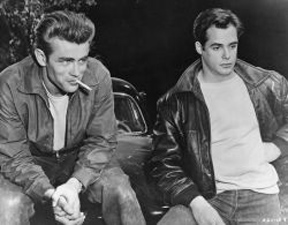

Dean and Allen prepare for their famous “chicken” run © WB

It’s night, and the only illumination is from the glaring lights of the cars and hotrods convened on a high seaside bluff in Southern California. Buzz Gunderson, black, pomaded hair over black leather jacket, and Jim Stark, in a deep red windbreaker, walk in silence to the edge of a cliff high above the Pacific. Buzz pulls a lit cigarette from Jim’s mouth, as friends might do, and takes a drag.

“This is the edge. That’s the end,” Buzz states with only the slightest hint of fear.

“Yeah. It certainly is.”

“You know something? I like you. You know that?” He’s a rough-looking young man, but Buzz sounds sincere. Earlier in the day they were at knifepoint for no better reason than they are now about race stolen cars toward the edge of this cliff to see which is “chicken.”

“Why do we do this?” Jim asks, but it is not a sign of retreat.

“You got to do something, now don’t you?” Buzz says with a resignation tinged with sadness.

Then, Jim (James Dean), and Buzz (Corey Allen) walk back toward their cars to finish one of the now classic scenes in American youth film history—the “chicken run” in 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause . In many respects Buzz’s words, which turn out to be near his last, were an anthem for the spate of films that emerged in the early 1950s, films about bikers terrorizing small towns ( The Wild One, 1953 ), or unruly inner city high school boys menacing their teachers ( Blackboard Jungle, 1955 ), films about cars and girls who admired the boys who drove them, films about sexual frustration, inter-generational tension, and mostly, about confused identity. They were films about, and for, the new, post WWII generation of American youth who had not only the mobility and privacy afforded by their cars, but also their own music, dress, and culture, and the sense of identity and direction those things did not provide and the repressed anger and rebelliousness they did.

Rebel Without a Cause is the seminal American film of the generation of youth in the American city at mid-century. But to appreciate its place of prominence we must look at the experience of youth in both the real and cinematic urban place in a broader sweep, perhaps holding Buzz Gunderson’s last question in quest of some answer. Back in 1955, Jim and Buzz were not only overlooking a cliff out into the vast Pacific, they were also standing on the cusp of a momentous social change in America—the emergence of the generation of youth.

By the mid-fifties surveys by movie producers had shown that a quarter of movie attendees were between fifteen and twenty-five years of age. Their titles, The Delinquents (1957) , Dragstrip Girl (1957), Hot Rod Rumble (1957) ; Reform School Girl (1957) ; High School Confidential (1958) ; I was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) (followed by Teenage Frankenstein, Cave Man, Monster, etc. ) tell the story well enough. Most of their themes were thinly-veiled, and often pathetic, attempts to express youth’s rebellion, against not being understood, even though youth did not quite understand itself.

Rebel might just well be the classic youth film, permuting all the elements of the youth culture: the social adjustments of high school, cars, manhood rites, dysfunctional families, repressed sexuality, and early death. Only rock and roll does not play a significant role. However, early death may well be responsible for giving Rebel its cult status. Buzz “wins” the chickie run, but only because his leather jacket becomes ensnared in the door handle, and he plunges over the cliff to a fiery end. Dean, who was a twenty-four year old “teenager” at the time he made Rebel, died shortly thereafter in a real car crash, becoming the first “martyr” of the tormented teenager generation. Co-stars Sal Mineo and Natalie Wood also met tragic premature deaths by murder and drowning respectively. [1]

There seems to be little guidance on “what to do” from the parents of these young rebels. They are almost ridiculous stereotypes, eating dinner in suburban homes in jackets and ties (mom wearing pearls), and completely misunderstanding the angst of their offspring. Jim’s father is cowardly, uxorious, and indecisive, lacking every trait Jim needs in paternal guidance. His mother is a social climber. It is little different for Judy (Natalie Wood), who still wants to be a little girl who can kiss her father, but is physically filled out to be provocative to an adult male. “You’re too old for that stuff!” her father scolds after rebuffing her affection with a slap, then apologizes by addressing her with a cutesy, childish nickname. Given that, Plato (Sal Mineo) doesn’t know how good he has it to have divorced parents who are not ever home. He’s cared for by a nanny, a large, sympathetic Black woman, who seems the best “parent” of the lot.

If the rebellion was against sexual norms of the times there is little evidence of it in Rebel . Jim seems only mildly infatuated with Judy, looking more for a friend than a sexual encounter. Their love scene in the old mansion near the end of the film is tepid and innocent, and the scene is rather suffused with allusion to family, especially with Plato’s bonding to the young couple as surrogate parents. The implication is that they just might just be better “parents” to each other than their bumbling natural parents have been.

A sub-theme of Rebel relates to geographic mobility. Jim complains that his family is always relocating (ambiguously) to “protect him.” He is always trying to fit in, to adjust, needing to make new friends, but is always awkward at it, provoking tough guys to call him “chicken” and, in his (on screen) lack of “coolness,” putting off girls. In some sense Jim’s plight relates to demographic changes in the American urban landscape. The film was made at a time when more parents could move to the suburbs to avoid unsavory urban influences on their children. But that was attended by a dislocation that required social skills for “fitting in” and dealing with the forms of prejudice and exclusion that prevail in such situations.

Rebel made James Dean the first youth film icon. With his mumbling, naturalistic delivery, his red jack of rebellion (which he is forever giving away), and in his real life, early death, guaranteeing his eternal youth, he was the forerunner of a hoard of youth entertainment media stars.

By the 1960s youth had found a cause or causes: racism, feminism and Vietnam (partly led by their surrogate father Dr. Spock). The rebellion turned political. It also provided a basis for another revolution that had been brewing—the so-called “sexual revolution”. If young people, even ensconced in their university dormitories, could take on weighty issues of society, then they were entitled, they seemed to reason, to act in other ways like adults. In fact, by engaging political and social issues, they had found a means to give social leverage to their age cohort. Accordingly, music, dress, and film began to reflect these changes. With events, such as Woodstock, youth culture began to create its own private history to go with its newfound culture of rebellion.

___________________________________

©2006, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 8.28.2006)

[1] Remaining “young forever” has also been achieved by several others in the youth star pantheon, among them Janis Joplin, Jimmy Hendrix, Freddie Prinz, Jim Morrison, Curt Cobain, and River Phoenix