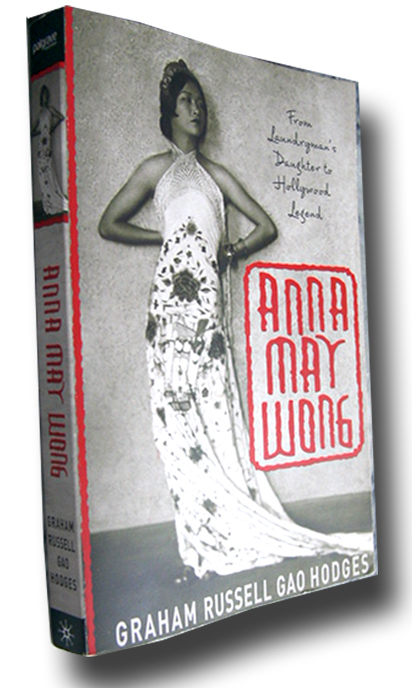

Before she died of a heart attack in 1961 Anna May Wong had “died a thousand deaths” on screen. As America’s first Asian lady of the movies, Wong was typecast as the “dragon lady,” the femme fatale of the East and other racist stereotypes of Asians who, for decades, were relegated to minor roles and “atmosphere” from the days of silent movies. Prevented from leading roles by de facto racist attitudes, and from even kissing a Caucasian on screen by “ de jure” equivalents, she persisted against conditions that might have sent a lesser person back to being a delivery girl for her father’s Chinese laundry in Los Angeles. But Anna May dutifully let herself be dispatched, or committed suicide, so that something could be done with the Asian “alien” character that American movie audiences couldn’t quite fit into the picture.

Before she died of a heart attack in 1961 Anna May Wong had “died a thousand deaths” on screen. As America’s first Asian lady of the movies, Wong was typecast as the “dragon lady,” the femme fatale of the East and other racist stereotypes of Asians who, for decades, were relegated to minor roles and “atmosphere” from the days of silent movies. Prevented from leading roles by de facto racist attitudes, and from even kissing a Caucasian on screen by “ de jure” equivalents, she persisted against conditions that might have sent a lesser person back to being a delivery girl for her father’s Chinese laundry in Los Angeles. But Anna May dutifully let herself be dispatched, or committed suicide, so that something could be done with the Asian “alien” character that American movie audiences couldn’t quite fit into the picture.

Asian parts seem to have been cast as though the Asian personality was regarded as so stereotypically “inscrutable” that Western audiences would be unable to apprehend the subtleties of a performance by a real Chinese in the role of a Chinese. Hence the series of over forty Charlie Chan films (from 1926 to 1949) in which the titular lead was played in “yellowface” by either a Scandanavian-born or American actor. Only the role of Charlie’s “Number One Son,” was played by Canton-born Keye Luke, although he is thoroughly “americanized”. Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth (1937) featured Westerners Paul Muni and Luise Rainer as Chinese in the lead roles. Then, of course there was the ultimate absurdity of John Wayne squinting his way through the The Conquerer (1956) failing to convince anyone that he was a credible Ghengis Khan while striding around Mongolia (actually Utah) in his unmistakable gait as though he were on his way to a cattle round-up in a John Ford classic. Producers still seem to rely on the American moviegoer’s confusion over Asians. Major feature films such asThe Joy Luck Club and Memoirs of a Geisha are able to cast, for example, Japanese as Chinese and vice versa, without any consequence to suspended disbelief.

Born right in LA, Anna May started out in silent films—with a role in Toll of the Sea (1922) when she was just seventeen—and made the transition to sound pictures with ease, probably because she had such small speaking parts, but also because she had a softy, sultry voice when called upon. Although she was under contract to Paramount the studio exploited her, paying her much less than they paid Caucasian actors for equivalent work. She supplemented with modeling work thanks to her exotic beauty and slim, shapely figure, from which she contributed to the educations of her several brothers and sister (including one son from her father’s Chinese wife who still lived back in Taishan in southern China). Anna May was the only one not to earn a university degree. Not that Anna May was without intellectual interests ort abilities. She read widely, counted artists, writers among her lifelong friends and acquaintances, and, when she boldly took herself to Europe in search of better roles, and acquired fluency in German and French. She became a bigger star there than in her home country.

Ironically, Anna May never seemed to be able to gain acceptance in China where her roles, as servants or Dragon ladies, were regarded as an insult to the Chinese culture. In part, the homeland Chinese disaffection for her work also owes something to the general low regard the Chinese have for “overseas” Chinese. Amazingly, Anna May was able to fashion a film career between the Scylla of Western discrimination, and Charybdis of Eastern opprobrium without going under. What may have sustained her was the respect and friendship she received from fellow actors, like Paul Robson, and cinematographer-director, James Wong Howe. She also formed friendships among intellectuals in America and Europe.

But the insults of negative stereotyping continued to haunt her films. In Shanghai Express(1932) Marlene Dietrich plays a call girl, but Wong (Hui Fei, the last name meaning a prostitute or concubine in Chinese) is cast more darkly, as a sullen and sultry “dragon lady” who is raped by a war lord. but eventually turns out to be the heroine of the film. She turns out to be the heroine, stabbing the warlord, Chang (played by non-Asian Warner Oland) and allowing all to escape his clutches. But the story quickly reverts to the love relationship between Dietrich and her male co-star. She actually had the lead role Bombs Over Burma (1943), a role that required she make love to a Japanese officer (Wong hated the Japanese and what they were doing to China) to save the people of her village. She kills the officer, but is herself executed.

Given a chance to give some non-stereotypical shape to a role Wong proved to be a facile and naturalistic actress. She was graceful in here movements and gestures, had a velvety voice, and could be expressive well-beyond the impassive inscrutability required of most of the characters she played. Still, most people don’t remember her, or know of her as Hollywood’s first Asian actress who blazed the through prejudice, discrimination and stereotypes to pave the way for Joan Chen, Nancy Kwan, France Nuyen, and Lucy Liu, and other Asian sisters.

Wong never married. She had several lovers, all of them Caucasian, at least one for whom she was “the other woman,” which never seemed to lead toward marriage or evolved into friendships. In that sense she seems well within the “tradition” of film and literature’s failed love affairs between Asians and westerners. However, she kept many friends, of different races and nationalities, for life. How much of that owes to her personality, or the fact that she was so unique and rare in her profession. What is clear is that at the personal level there was far more depth and dimension to her than was ever allowed to be expressed in her film roles. Her place in film history is a bit like many of the roles she played; she was the inscrutable Asian, often in the shadowland between East and West.

___________________________________

©2006, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.11.2006)