Australia has long been known as a place with an exotic menagerie. Flipped down-under-wise, its bestiary exhibits an antipodean cockeyedness. One almost expects creatures to be not only marsupial, but to be equipped with suction feet to keep from falling off the planet. That may be just some northern hemisphere centrism about a place where water putatively whirlpools in the opposite direction when going down (up?) the drain. Such matters might seem to dominated in a place where not much has been going on down there” that is not measured in geologic or evolutionary pace of time. I confess to seeing it, with a slight squint of the eyes, rather like a set for America in the 1950s.

Australia has long been known as a place with an exotic menagerie. Flipped down-under-wise, its bestiary exhibits an antipodean cockeyedness. One almost expects creatures to be not only marsupial, but to be equipped with suction feet to keep from falling off the planet. That may be just some northern hemisphere centrism about a place where water putatively whirlpools in the opposite direction when going down (up?) the drain. Such matters might seem to dominated in a place where not much has been going on down there” that is not measured in geologic or evolutionary pace of time. I confess to seeing it, with a slight squint of the eyes, rather like a set for America in the 1950s.

But in the pens of a Patrick White, Colleen McCollough, Peter Carey, or the cinematic view of Peter Weir or Jane Campion Australia proves to be mysterious, funny, brooding, adventurous, rich and varied social setting with its own unique history. Much of that is thanks to the English, who enter the story, and begin the continent’s social history in the 18 th Century. With its swelling population and concomitant crime rate the faraway colonial acquisition seemed to possess great penitential prospects. “Transportation,” they called it, being sent down, mostly for life, and mostly for offenses that would receive a slap on the wrist today, to a place where most of the land is inhospitable, where every other critter has a venomous bite and disposition to match, and where the aboriginals slathered themselves with fish oil and still, technically, lived in the Neolithic.

Even more bizarre is Tasmania, a place where even Aussie’s might “transport” unrepentant miscreants. Further “down under,” across the Bass Strait and below the 40 th parallel South, the shark-toothed-shaped island once called Van Dieman’s Land is the locus of Matthew Kneale’s splendid English Passengers. Kneale’s story of the follies and brutalities of the English is narrated by no less that twenty different members of his extensive dramtis personae , giving the lengthy tale a somewhat cubistic structure in which we see a clash of civilizations played out from multiple perspectives. When the fact that the tale alternates between two different time periods (the 1920s and the 1850s) is added to the different voices its is evident that the author’s skill in weaving them together and finally bring the characters together in the same time frame was likely responsible for the book’s being short-listed for the Booker Prize.

If there is a center to this narrative it is shared by Captain Illiam Quillian Kewley, a Manxman bent on smuggling a contraband of brandy and cigars to Australia in 1857, and a half-caste aboriginal boy, the product of a rape who is spurned by his bellicose mother and educated by well-meaning colonials in the 1820s, but only after they have removed his clan from Tasmania to Flinders Island in the Bass Strait. The title refers to passengers that Kewley is required to take on as cover and finance for his voyage: The Rev. Geoffrey Wilson, a sanctimonious Bible-thumper who believes that Tasmania might well have been the Garden of Eden, and Dr. Thomas Potter, a pseudo-scientist who is looking for proof in his thesis about the fundamental differences among the races of the earth, the English being at the apex.

It is that English superiority complex that Kneale dismantles with the assistance of well-wrought characterizations, clever plotting, and intensive research into the history of the settlement of Australia. The brutal penal system, often overseen by officials with more criminal minds than their prisoners, spills over into the racism and literal genocide on the aboriginal people who are completely eradicated from Tasmania after being hunted down and massacred by settlers, going the way of some of the local fauna, such as the Tasmanian wolf. Typical of imperialism’s religious impulses there are the “well-meaning” soul-snatchers who at least want to see the dispatched locals sent off as Christians.

Captain Kewley’s quest is simply to make a killing selling booze and nicotine to the colonials; half-caste, Peevay (renamed George Vandieman by the settlers) is based on some actual aboriginals who unsuccessfully revolted and managed to kill some of the marauding settlers with their stone-age spears. Their space-time coordinated nearly intersect near the end of the book, when Kewley, after many a mishap, manages to sell his contraband only to suffer a mutiny led by Dr. Potter, who he has just rescued after the latter’s ill-fated expedition to obtain more evidence for his race thesis. Peevay steals aboard the ship to rescue his own mother’s bones, which Potter intended to return to England and put on exhibit.

Kneale’s characters and plot twists are hilarious, but the reader is always aware that the roguish and foolish cast and their changes of fortune have the ring of dark truths and the evidence of history just beneath the fictional surface.

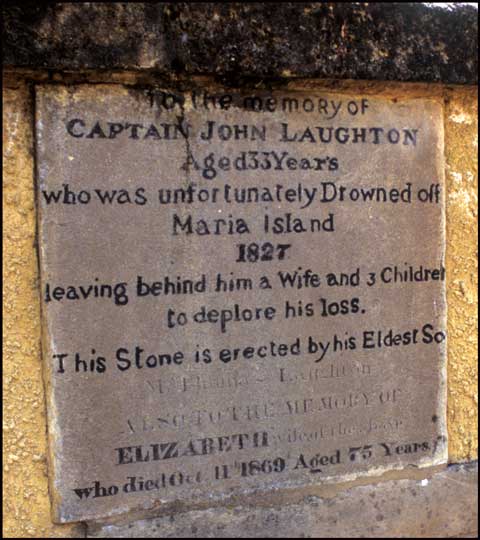

Down-under exacted its revenge on the exploiters and brutalizers, often with its physical inhospitality. A few years ago I strolled through a cemetery in Hobart, Tasmania, amazed that, even accounting for the headstones placed there more than a century earlier, so many settlers from “Up-above” met early premature demise from disease and accident. The author might have been writing a more philosophical epitaph for many of those that I observed when he has one of his characters ponder, “How suddenly the hand of fate falls among us! How near, every instant, as we blindly go about our lives, lost in the comfort of routine, lurks the icy embrace of death.” Looking back through Kneale’s English Passengers makes it easier to smile at the fates of people when hemisphere’s collide.

©1992, UrbisMedia

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 10.9.2005)