©2005 UrbisMedia

Even a hack jazz pianist like myself cannot go too long without sitting down to a keyboard and seeing what one can do with the chords and melody lone of some great tune—maybe On Green Dolphin Street , or Angel Eyes , or Stella by Starlight —that’s been playing in your head all day, or you caught of chorus of on the car radio. When you’re a long time away from your piano at home you start looking for keyboards the way a junkie is needing to see his dealer.

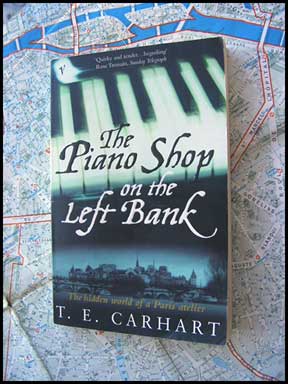

When I picked up T.E. Carhart’s book it strangely related some of the same piano yearnings I had experienced when I spent half a year teaching in Paris in 1989. He was living not far from where I lived and where he would pass a piano atelier when he walked his kids to school. He was drawn to back to the shop, much the same way I was when I passed a piano retailer on my way to classes at the University of Paris. I salivated at those shiny uprights and consoles, and majestic grands with strange French brand names on them, making little grease spots on the window with my nose and cheeks as a pressed for a better view.

Carhart seemed to do much the same, but his shop was an atelier that refurbished and repaired pianos in a smaller, and still, cobbled, street. And he, being in Paris longer than I, was bent on buying a piano. Moreover, he obviously didn’t live in a studio apartment like mine.

Carhart is what is often called a “trained” pianist, not somebody like myself, who can barely read a note and quit being “trined” after six lessons, and he played what might be called s “serious” (read “classical”) music. Like most pianists he love the instrument, and what makes this book a pleasure is that he finally gathers the courage to knock on the door of the Desforges piano atelier , but gradually gains admittance to its rather guarded and secretive interior by befriending Luc, the heir apparent to the shop’s owner, who has a deep affection for pianos as well.

The atelier is described as an almost Willie Wonka world of pianos in various stages oif assembly and repair. There are mostly French pianos such as Erards and Pleyels, but also German, Austrian and American pianos. Carhart, who hasn’t played much since his youth decides that it’s time to purchase one, and Luc, who tries to match instruments with customers because he also regards pianos as “members of the family,” matches him with a rebuilt Stingl grand.

I have often wondered how grand pianos made their way into upper story European apartments, but Carhart’s description of the arrival of his Stingl clearly astonished him as much as this reader. It was hauled up the stairway strapped to the back of a somewhat too old barrel-chested man, without any mechanical assistance! Even without the legs attached, this is an almost superhuman feat.

I thin that Luc is right, a piano is something like a member of the family — one that is always ready and willing to let you express your joy, Assuage your sadness, or just take you out of yourself and into the realm of harmonics, rhythm, and melody.

If I had mu own grand piano in Paris I already know what I would sit down and Play: Cole Porter’s I Love Paris. It’s such an apt tune, murmuring along lugubriously in a minor key like the city itself on a chilly slate grey Autumn day, then, almost bursting into a major chord, as if one had just emerged from a narrow Left Bank lane onto a view of the façade of Notre Dame. Like Porter, one would have to spend some time in the city to come up with a tune like that.

But I’m getting away from Carhart again. Through his experience in the atelier we get to know the mechanics of the piano and to understand that what goes into producing great piano sound – and there is nothing, other than the human voice, that approaches its beauty – is made up of a complex permutation of the elements of wood, metal, felt, wire, and the dynamic tension of a stringed instrument tuned to perfection.

That experience rekindled Carhart’s interest in taking lessons again, and his daughter soon joins him. I was impressed that the school he chose for her did not engage in piano competitions because, as they put it : “On ne fait pas de musique contre quell qu’un.” I always thought that playing music competitively (there was even a movie about this, The Competition , a few years ago) was a really stupid notion. One should play music the way they feel the music, their own way, not to “win.”

I finally got the courage to enter the piano store I had discovered in rue Cardinal Lemoine. By feigning interest in purchasing a console I was allowed to try out a few of them. But he propriator got one to me, In think, and gently let me know that he had some practice studios in the basement pour louer . So, a couple of time a week, on the way back from class, I would rent one for about five bucks and hour. Each time I began with Porter’s I Love Paris.

Back home in San Diego I play a Yamaha electronic keyboard. It has excellent sampled sound and weighted key action. But Carhart planted the idea in my mind to one day own whaty is considered to be the world’s finest piano. It is a brand I knew nothing about until I read Carhart’s book. Like exclusive hand made Italian racing cars There are only about seventy Fazioli pianos built each year, with sound boards of red spruce found only in Italy’s Val de Fiemme. But they can cost as much as $160,000; so, like Carhart, I’ll have to keep checking for one to turn up at un bon prix from the piano shop on the Left Bank.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 5.2.2005)