©2005 UrbisMedia

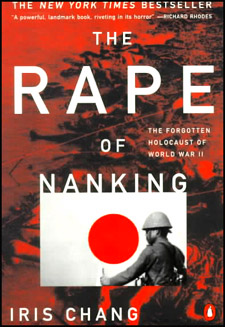

As Chinese youth besiege the Japanese embassy in Beijing, venting their rage at the prospect that Japan might be admitted to the UN Security Council I can only wonder what Iris Chang, the young Chinese American author of The Rape of Nanking would think. Who can know what part her internationally acclaimed book played in the consciousness of China’s youth in their grandparents’ horrific history. But it must have played some part.

Chang brought that history to light in the West, an historical incident that lingered for over sixty years somewhere between faint recollection for the WWII generation, to complete ignorance for most of those younger. And, giving impetus to the protests of China’s youth is that the current generation of Japanese may be subjected to the national denial of their parents and grandparents through a bowdlerized history of Japan’s aggression in China. (cf. No. 11.3 on the museum in Nagazaki)

I spoke with Iris on the phone a few years ago when she was being interviewed on NPR. I was gathering information for a project of my own about the Japanese military’s Unit 731, which engaged in biological experiments using live Chinese prisoners. Iris was well informed on that subject and had encountered some former Japanese participants in Unit 731 when she courageously did a book tour in Japan. But Unit 731 was operating in Harbin and a few places in S.E. Asia, and Chang’s book concentrates on what happened in Nanking in several weeks at the end of 1937 and the beginning of 1938.

That was when the Japanese Army stormed the ancient walls of Nanking and committed one of history’s greatest crimes on its few remaining soldiers and mostly its innocent civilian population. Much of the documentation for the mass executions and rape-murders were provided by the Japanese themselves. A picture of two officers who engaged in a beheading contest (the first to kill 100 Chinese was the “winner’), ran in a Japanese newspaper as a glorious achievement. Photos of men tied together and buried alive, or set ablaze, or tied to stakes and used for bayonet practice, often have smiling and laughing Japanese in them. Women were run down, raped and butchered, forced into pornographic photographs, and sent off to brothels for the Japanese Army.

The museum in Nanjing says there were at least 300,000 Chinese killed; the Japanese government maintained for years that it was really only about 3,000 that were sort of “collateral damage” in a battle for the city that that was limited because the Nationalist Army’s General Tang was ordered by Chiang Kai-shek to retreat from the city with his troops. Aside from an International Safety Zone for foreign embassies the people of Nanking were left defenseless.

Chang’s book also documents that there were foreigners who attempted to save the Chinese, cloistering many in the International Zone, and in the case of some, such as German businessman, John Rabe, rescued thousands from certain death. Today, inside the Nanking Massacre museum is a smaller museum dedicated to Rabe.

The protests in China today may have the cynical fingerprints of the Chinese government on them, not only to keep the Japanese out of the UN Security Council, but to gain advantage in other disputes, such as the sovereignty over some islands. So be it; if the protests bring the truth if the Rape of Nanking out into the light once again it will at lest be some testament to the memory of Iris Chang.

I say “memory” of Iris because this beautiful, brilliant author of four books and many articles took her own life last November. No one knows exactly why, not even the husband and two-year-old son she left behind. It is known that she suffered from depression, and researching the Rape of Nanking can’t have been a tonic for depression She was only 36, and it so seems fitting to un-round the victims of Nanking to 300,001.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.22.2005)

This subject merits a few other references. Among those I have read on Nanking and the Japanese in WWII are:

Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony , Yenbooks, 1996 [ironically, I bought this book in Kyoto]

Hua-ling Hu, American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking , Southern Illinois U Press, 2000 [this is the story of Minnie Vautrin, who was dean of studies at Ginling College in Nanking in 1937]

John E. Woods (trans), The Good Man of Nanking , Vintage, 2000 [this is a translation of the diaries of John Rabe]