© 1991 UrbisMedia

Israel, April 1990. “Joe Angel,” he said when I asked him a second time to pronounce his name in Hebrew for me. He saw my look of disbelief and repeated: “Joe Angel. That’s what my name was in Italian, Giuseppi Angelo. So when I came here I just translated it into Hebrew.”

I was interviewing Joe for a documentary project involving auspices from the US, Israel and Egypt. “Desertification,” the process of the transformation of formerly verdant and arable land into desert sand is a silent and seemingly inexorable threat to prosperity and peace in a great swath of geography from the Sahara to across the Middle East. If ways could be found to arrest, or cope better with this process, the supporters of this project contended, even bitter enemies might find “common ground” and a way to live together in the Promised Land.

Joe Angel is an Italian Jew and Israeli citizen, which he has been since he emigrated from Rome to Israel in 1951. Short, with a paunch, and pure white hair over a ruddy complexion he reminded me a bit of David Ben Gurion, but with a better haircut. Joe is an agronomist, and it was his field of melons we were standing beside in the Negev desert not far from Beersheva.

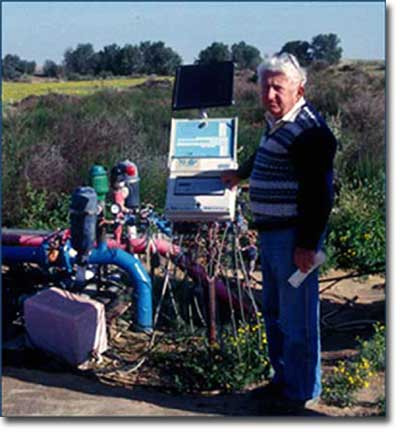

This wasn’t just any old field of melons; this was a field of high-tech melons, melons being raised on soil that looked like kitty litter. Around the perimeter of the field was a short little wire fence of a couple of wire about a foot high. It was to keep little desert varmints from having a melon party. At the corner where we stood was an ensemble of distinctly un-agrarian looking equipment: a couple of large plastic fluid containers, one with a fertilizer, the other a reservoir for “sweet,” or fresh water. Next to that was a post about seven feet high, on which rested a panel of photo-electric cells. The solar panel was connected to a computer attached further on down the pole. The computer ran the little melon farm.

Arrayed over the field of melon plants, if one looked carefully, were little black plastic hoses, drip-irrigation tubes, following the rows of the plants. The Israelis were the wizards of drip-irrigation. Joe Angel had told me that, while this might seem like the latest thing in agriculture, it was actually an ancient people from nearby this area, then called Nabatea, on the other side of the Dead Sea, who practiced this method of watering plants back in biblical times. The Nabateans used to place stones next to each plant, on which, during the cool desert nights, would condense moisture that would then drip off them to the base of the plants. Drip-irrigation had the same effect, ideal for growing things in the desert, where spraying water is wasteful and inefficient.

Water, particularly “sweet” water, or rather the lack of it, is the reason for all this high-tech farming. There isn’t much of it in these parts, and what there is must be shared with Israel’s neighbors. Religious and historical hurts may fuel much of the unrest among the nations of this region, but water has the potential to raise the stakes to a new level.

That’s one of the reasons the Israelis have improved upon the methods of the Nabateans. Beersheva means “seven wells” in Hebrew, so there is some fresh water in the vicinity. But these days there is not enough to go around, so the trick is to find a way to put some of the less desirable water to work. Deep below the desert sand there is plenty of water, but it’s very saline since the aquifer is actually a shelf that begins in the Mediterranean sea. Used by itself, salt water ruins crops and degrades soil; but used judiciously along with fresh water and fertilizers, the Israelis have discovered, the desert can be made to bloom with crops and profits, maybe even peace. Israeli scientists have even gone the Nabateans one step better by devising a “pulse” irrigation system that is more effective than the constant drip method. The pulsing of a careful mixture of fresh and salt water and fertilizers is managed by the sun-powered computer.

The Israelis are justly proud of these accomplishments. There were trellises for growing cherry tomatoes that could be plucked them from the vines to eat like candy. They had the sweetness of candy, I learned, because they had been grown partly with saline water. Many of the agronomists had bowls of them on their desks, and ate them the way Americans might jelly beans or peanuts. If they could turn this science into a sweet deal with their Arab neighbors it might put some of the promise back into the “promised land.” [to be continued]

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 4.10.2005)