©2005 UrbisMedia

Back in 1989, while living and teaching in Paris I did a good deal of café reading. One selection that stuck with me was a biography of renowned war photojournalist Robert Capa, whose career spanned from the Spanish Civil Was (the famed photo of the soldier falling the instant after a bullet has killed him) through WWII and the D-Day beach assault photos he took that were destroyed by accident, to French Indochina, where his luck ran out and he was killed by a land mine.

Capa’s boldness and his picaresque life probably inspired more photographers to throw themselves into the perils of battlefields all over the world more than any other photojournalist. This, in spite of the fact that his demise is ever a reminder that at any moment what one sees in the viewfinder might be that last image in one’s life, that the platoon you got out on patrol with, the assault you want to document, or the helicopter you jump on because there is a possible story and telling photos where it is going, might be your last mission.

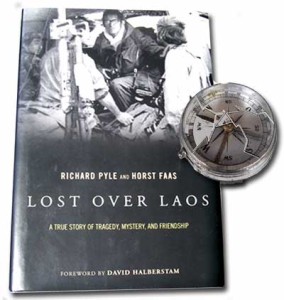

Lost Over Laos is the story of four international photojournalists who jumped on a UH-1H “Huey” helicopter at Ham Nghi to photograph the US-backed incursion of the South Vietnamese Army into Laos to cut the supply line of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The chopper had Vietnam Air Force markings on it because, as you might remember, U.S. personnel weren’t supposed to be in Laos. That was the last that was seen of Larry Burrows of Life magazine, Henri Huet of the Associated Press, Kent Potter of UPI, and Keisaburo Shimamoto of Newsweek , respectively, a Brit, A French-Vietnamese, and American, and a Japanese. This was near the end of the war (American forces were already withdrawing) and with Laos sealed off, what really happened to these men has to wait for years.

Pyle and Fass were colleagues—renowned war photojournalists in their own right—and friends of the four photographers lost somewhere in Laos. They bring them back to life in this book by chronicling their exploits, their personal lives, and through some of their photography. War photographers are a close knit cohort in many ways, the ways that danger generates a curious camaraderie among me with the sang froid to steady shaking hands and get the shot while being shot at. Few of them are wise-cracking hot shots that would be aptly-played by the latest Hollywood hunk. Larry Burrows, a the dean of the group, comes across visually as a cross between Arthur Millar and Billy Holly. Authors Pyle and Faas look more like accountants than the kind of guys who would plunge into a free fire zone armed with a Nikons or a Leica.

That these were a special breed is attested by the photographs, many of them already published, and several familiar to anyone who was paying attention during the long years in which the covered the war. Some, like Huet, had been shot up as many times as he won international photo awards.

Pyle and Faas has to wait 27 years to go back and search for their lost colleagues and, with the assistance of a task force of workers, located what remained of the crash site, littered with crumpled parts of cameras, lenses and other photographic equipment that would have been of no use to scavengers. By tracing serial numbers on the equipment they were able to verify that they finally hand “found” their friends and colleagues.

An interesting comparative statistic comes out of this book. During the 1960 –75 period that brackets the Vietnam conflict some seventy journalists were killed. There was also no such thing as “imbedded” journalists in Vietnam. In the year or so of the Iraq war there have already been thirty-five journalists killed, eleven by American fire.

___________________________________

©2005, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 3.21.2005)