Last week Trump announced his promise to give another $19 billion in support to the farmers who have been economically injured by his trade war with China. That gift, of course, is likely to be financed by bonds that might well be purchased by the Chinese, which they can then add to what America owes them from their purchase of the off-the-books debt that they financed of George Bush’s wars with Iraq and Afghanistan. This is typical Republican fiscal legerdemain in which our attention is supposed to be distracted by their insincere cries to do something about the national debt (which they blame, of course, on democratic supported “entitlement” programs). In the end, it is we, the taxpayers, who will pay for this welfare program for farmers—many of whom still enthusiastically support Trump and his economic policies—and we will end up paying more for their produce as well. That’s how we do it in the promised land of America and, in fact, as part of our self-delusion it turns out that farmers, those paragons of economic independence and self-reliance, are, as they have long been, the most entitled welfare recipients of American society.

Indiana poet-journalist James Whitcomb Riley once wrote: “Without the farmer, the town cannot flourish. Ye men of the streets, be cordial to our rustic brethren. They are more potent than bankers and lawyers, more essential to the public good that poets and politicians. Do all you can for them.” Riley penned this sentiment in the nineteenth century, in the Midwest, when farmers were still in coveralls, and traded most of their produce in their own regions and could barely find China on a map.

That was then; this is now. And now is the age of globalization and farmers can easily find China on Wikipedia on their Chinese-assembled iPhones and check whether the Chinese have tariffed their soybeans and corn in response to Trump’s dumb-ass trade war with them.

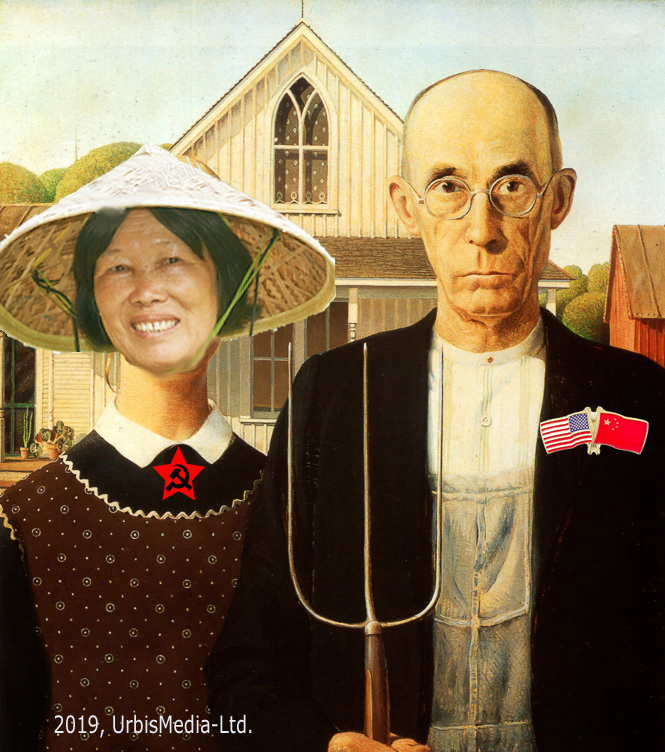

In the saga of American agriculture, we may have to begin to regard farming, not as the idyllic independent yeoman myth that has influenced much of the American consciousness, but as the corporate enterprise it is has evolved to be.

The farm and the city have been locked in an economic embrace since the very first cities ten millennia ago. If cities were to grow and prosper their residents needed their hands for urban work; somebody else had to feed them. Likewise, farmers needed the city market to prosper. The relationship has been necessary, but often contentious, especially in competition for land in the vicinity of growing cities. Today there may be fierce competition between them for resources like water as well.

The reciprocity between city and farm hasn’t changed much over the centuries, but both cities and farms have changed a great deal. By 1920 in America more people were living in cities than in rural areas. A good portion of the growth of cities was fueled by rural émigrés, pushed from agriculture by hardship, drudgery, and the growing mechanization of farming, and pulled toward the city by its lures of excitement, and the opportunities of employment in its factories and businesses. On the farm there was one occupational opportunity—Farmer; in the city, there were ever-expanding possibilities. It has been one of the ironies of the American experience that many an erstwhile farmer has ended up working in factories making the tractors, threshers, and combines which would replace and displace others like himself. By 1970 more than ninety percent of American were classified by occupation and/or residence as “urbanites.” Only about six percent of us were farmers by the latter date.

Today, one farmer feeds over fifteen city folk, with leftovers for export and governmental purchase. He does it with a lot of equipment, a lot of technology, a lot of petrochemicals, a lot of water, and a lot of political influence that results in agriculture being a far greater recipient of government largesse

One of the cornerstones of agriculture’s political influence rests on a is the romantic myth of the “yeoman” family farmer of American folklore, who, harnessed to his plow, independent and self-reliant, labored proudly in an idealized rusticity. Regarded as the bedrock of America, agriculture to the yeoman farmer was not so much a business as a way of life, a tradition, and an almost sacred covenant between Man and Nature. But bedrock or not, the yeoman farmer is an endangered species bordering on extinction.

Consequently, we are more likely to encounter today’s farmer in Washington or a state capitol testifying before an agricultural committee about price supports, sitting in a corporate board room, or lobbying a legislator. An expensive three-piece suit will have replaced the coveralls, a more appropriate costume for plowing financial furrows with a depreciation table for massive tractors and combines. Our contemporary farmer’s “farmhands” now consist of accountants, lobbyists, and ag-school graduates. The yeoman farmer has become the “agribusinessman”; he has taken on city ways.

But myths die hard. In the minds of many Americans the farmer is still an individual, not a corporation, still struggling to be self-reliant, not dependent on government loans, price supports, and subsidies, still closer to God than mammon.

There is plenty of documentary evidence for this momentous social transformation, which has accelerated in this century. Since the mid-1930s, when there were almost seven million farms in the United States, virtually all of them family-owned and -operated, that number has eroded to about two-thirds of a million. Today, less than one-sixth of the nation’s farms are family farms.

Nevertheless, it is the resilience of the myth that gives farming not only its sentimental influence but a disproportionate political influence as well. Surveys record a surprisingly high number of people who, when asked where they would like to live, would choose the farm. Most of those surveyed, of course, are born and bred urbanites whose principal or only experience with agriculture beyond the produce section of the supermarket comes from Waltons re-runs. Even rural realism films like Country, The River, and Places in the Heart continue to portray the American farmer as a rugged individual beleaguered by the weather, the government, greedy land developers, and debt. Such may be the case for many small farmers; but the U.S. Department of Agriculture reports that the average net worth of California farmers is around one million dollars.

Successful agribusiness leads both to and from successful “agripolitics.” Sparsely populated farm states enjoy a disproportionate political representation at the national level, and even in highly urbanized states, farmers have considerable clout. The result is a bewildering array of government low-interest loans, tax breaks, price supports, buy-back provisions, and, of course, payments to some farmers not to produce crops. The total of all this assistance has been estimated to amount to over a quarter trillion dollars in during the 1980s. Moreover, agriculture, which commands over eighty-percent of the states’ water supply, often pays only a fraction of what it costs industrial enterprises and other urban uses.

A five-year drought has therefore brought to light some curious paradoxes. Cities, which purchase agriculture’s produce, have helped to develop technologies which h made agriculture more efficient by making it a more capital-intensive agribusiness. But cities have not been paying for the products of agriculture under anything approximating a competitive, free-market pricing system. Farmers in California are already making the argument that, if their water allotments are cut, city people may end up paying more for agricultural products. That may be so, but it is tantamount to invoking the laws of supply and demand only when it serves agriculture’s advantage. Supply and demand do not seem to apply in the pricing of agriculture’s inputs to production. In any case, urban consumers are already paying more than they suspect for agriculture’s products by way of the government subsidies and other financial advantages which farmers receive.

Meanwhile, urbanites and urban business face cuts of up to 50%, in their seventeen-percent of total water usage, which may well threaten the productivity of a vast array of industrial and busyness enterprises, causing increased unemployment and business failures.

Some will argue that city people have been wasteful in their water-using ways. There is enough truth to such claims to take seriously the necessity for cities to cut back and conserve. Some have placed the blame on that general purpose bugaboo–urban growth. But agricultural practices are hardly free of like charges. Water intensive crops such as rice are inappropriate crops for arid and semi-arid regions, and more economical irrigation methods, such as drip-irrigation (versus flood and spray systems) could be employed more widely.

There is plenty of culpability to go around as we shape policies to address the problems created by diminishing water supply but it appears that cities, which are already getting the short end of the deal, might well get more blame and less water than they deserve.

If we are to deal realistically with problems of water supply, which is only the latest chapter in the uneasy relationship between the farm and the city we first must dispel the American agrarian myth and the romantic sentiments and political biases which it has engendered. Farming today is agribusiness and big business at that. All the subsidies we can afford will not bring back James Whitcomb Riley’s noble yeoman farmer, any more that bricks in toilet tanks and shorter shower will solve the water problem.

If these problems were not enough, along comes Trump.

___________________________________

©2019, James A. Clapp (UrbisMedia Ltd. Pub. 05.31.2019)